Might As Well Jump

When serving as a marine naturalist, one of the questions I am most often asked about whales is “Why do they jump?”

When whales jump it is called “breaching” and the answer to why they do it is not a simple one. Why whales do something depends on context; there is not just one trigger for breaching. This is no different than interpreting human behaviour. For example, if someone is tapping their foot, it could indicate irritation, having an itch, impatience or hearing a good tune!

The breaching of whales can be related to socializing, feeding, mating, communication and/or defence. Of course, when whale calves breach, it is often related to “play” behaviour which leads to good brain development and coordination. Ultimately, I believe that the high energy behaviour of breaching must somehow lead to a gain in food and/or increased success in passing on DNA.

Let me share two very specific and recent “cases” of breaching with you; one of which was witnessed by many residents of Alert Bay.

While out in our area with Orcella Expeditions last week, we saw an adult humpback whale breach some 30 times and also witnessed a mature male mammal-eating killer whale (“transient” or “Biggs killer whale”) breach within 30 meters of Alert Bay’s shoreline.

I have never seen anything quite like these two awe-inspiring events.

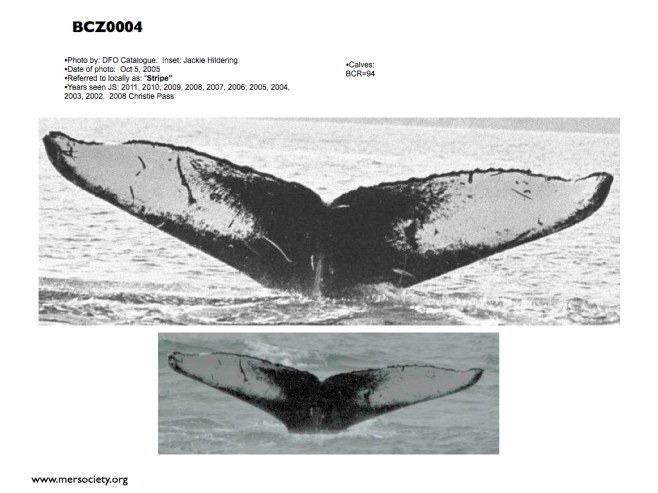

Humpback whale, ‘KC” on August 30th, 2011. One of the some 30 times he breached in less than 2 hours. Photo: Hildering

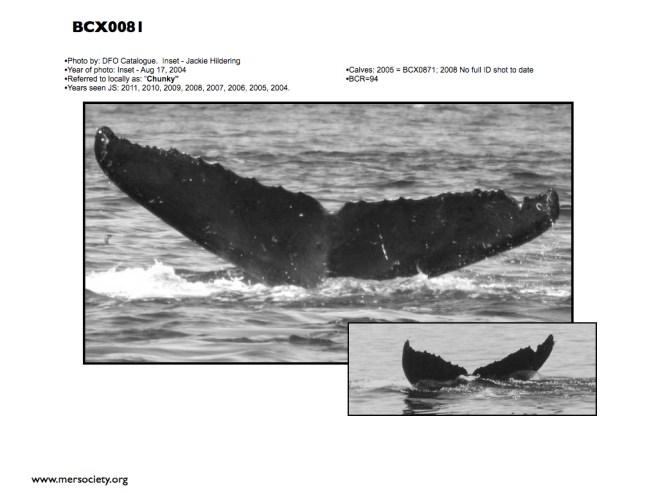

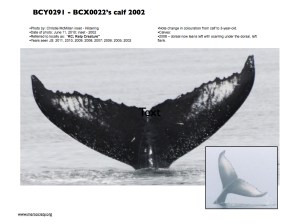

The humpback that breached so often was “KC” (BCY0291) who was born in 2002. Initially, I believe the breaching was triggered by the presence of highly vocal fish-eating killer whales (“residents”). Humpbacks do not have teeth with which to defend themselves but they do have whale barnacle studded fins and a whole helluva lot of heft to throw around so even the mammal-eating type of killer whales very rarely interact with adult humpbacks.

My interpretation is that KC was not habituated to the killer whale dialect he heard that day (I15 and I31 calls) and was making sure he made clear “do NOT mess with me!”. He was posturing to the killer whales. After his killer whale encounter, he turned around and came upon another humpback whale and again started breaching and making very forceful exhalations called “trumpeting”. Was this communication to the other whale about the presence of the killer whales? Was it related to a dominance display that may have to do with mating? I may never know for sure but it is very interesting that KC’s incredible bout of breaching seemed to lead to other humpbacks breaching as well.

Mature male mammal-eating killer whale “Siwash” breaching in front of Alert Bay on August 31, 2011. Photo: Hildering.

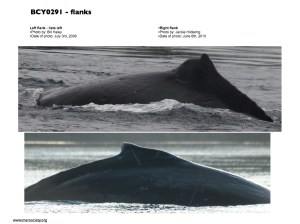

And then . . there was the mind-blowing, highly witnessed breaching of the 27 year-old killer whale “Siwash” (aka T10B ) in front of Alert Bay. Siwash was travelling with a group of 20+ other mammal-eating killer whales. As mammal-eaters, this type of killer whale has to be stealthy and unpredictable and therefore, they are most often far less vocal and surface active than the fish-eating killer whales. This certainly wasn’t the case as they bounded past Alert Bay last Wednesday evening! They were swimming on their backs; fin slapping and travelling right past the shore; calves were “cat and mousing” small diving birds – whacking them around; and there were even male sex organs to be seen at the surface!

What was going on? Let me state the obvious – they were socializing. Their bellies must have been full enough to allow them to throw stealth to the wind. These particular whales would most often not travel together so the socializing might even be related to mating.

But ultimately . . . in trying to understand the behaviour of these sentient beings, we have to have the humility to accept that we may only ever have hypotheses for why they do what they do. It is the stuff of awe and wonder that the mighty Max̱’inux̱ were so visible to the very people that have such a strong cultural connection to them, as they swam by Alert Bay . . . . “Home of the Killer Whale.”