Who Goes There? Sea Otter feeding pits

Who goes there?!

Or should that be – who DIGS there?!

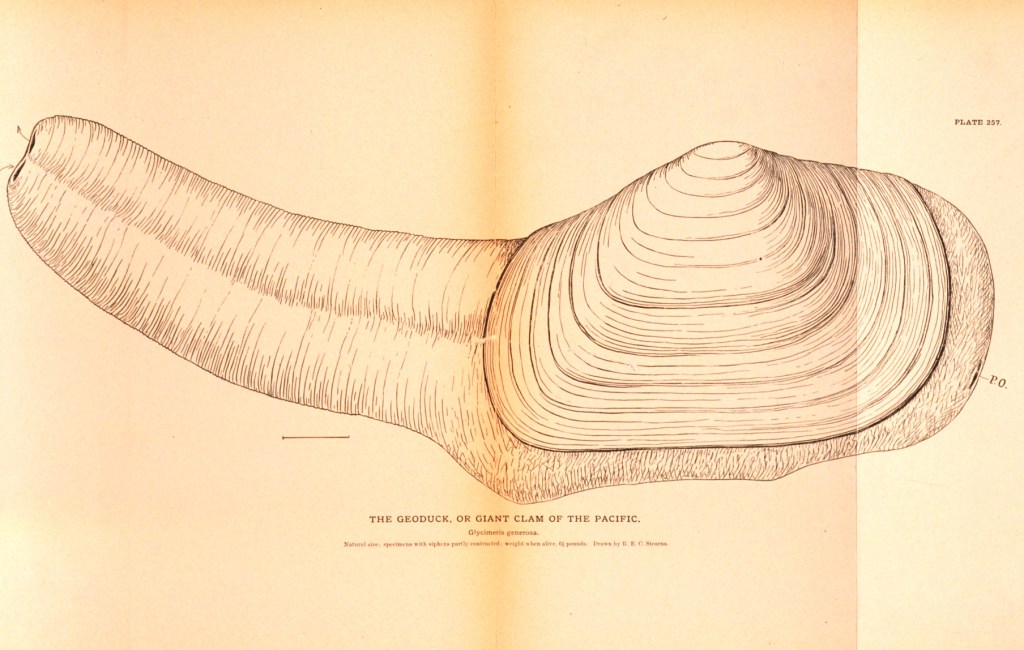

This is the pit resulting from a Sea Otter digging after a Pacific Geoduck – a very large, very long-lived clam species.

Photo: January 1st, 2025, ©Jackie Hildering.

If you see a Sea Otter going up and down in the same location without coming up with prey the first time (and breaking it open on their belly), this is likely what is happening.

Photo: March 27, 2021, ©Jackie Hildering.

Geoducks have very long siphons (neck or shaft) and can be buried 1 metre below the surface. So it’s quite the endeavour when Sea Otters excavate Geoducks. My photo of the deep pit should aid in understanding why this is the case!

Source: Goode G. B. (1880). The Fisheries and Fisheries Industries of the United States via Wikimedia Commons.

Sea Otters are reported to be able to dive up to 5 minutes (more often ~1 minute) but that’s unlikely when exerting themselves when digging like this.

Did the Sea Otter get this Geoduck? We don’t know for sure but there was an empty shell of a Geoduck near the pit.

Note that we did not dive in the presence of Sea Otters. Diving or swimming with marine mammals is illegal in Canada.

Photo: April 20, 2019, ©Jackie Hildering.

Photo: January 9, 2021 ©Jackie Hildering

Background on Sea Otters in British Columbia

Sea Otters were completely wiped out (extirpated) with the last verified Sea Otter in Canada having been shot in 1929 near Kyuquot (NW Vancouver Island).

There are now over 8,100 Sea Otters off the coast of BC (Nichol et al. 2020). How did that happen? Around 89 Sea Otters were translocated to the outer coast of Vancouver Island from 1969 to 1972 (as a mitigation measure for nuclear testing in Alaska).

The population grew (and spread out) from there. And yes, they eat a lot. Even with their incredibly dense fur (which made them so “desirable” in the fur trade), they need to fuel their furnace by eating up to 1/4 of their body mass daily to survive in the cold ocean.

More Sea Otters = more kelp forests (since they eat the urchins that eat the kelp) = more habitat, more oxygen, more food, and more carbon sequestration.

Sea Otters are recognized as a species of Special Concern in Canada.

More Information

Sea Otters

– CBC, To oblivion and back – How sea otters are radically changing the West Coast ecosystem 50 years after their return to B.C.

– Nichol, L.M., Doniol-Valcroze, T., Watson J.C., and Foster, E.U. 2020. Trends in growth of the

sea otter (Enhydra lutris) population in British Columbia 1977 to 2017. DFO Can. Sci. Advis.

Sec. Res. Doc. 2020/039. vii + 29 p.

Pacific Geoduck

– DFO, Geoduck clam

– IFLScience, What Is a Geoduck? The Ocean’s Giant Burrowing Clam

– iNaturalist.ca, Pacific Geoduck