A Pacific Spiny Lumpsucker – and a Lump in My Throat

See him?

The Pacific Spiny Lumpsucker?

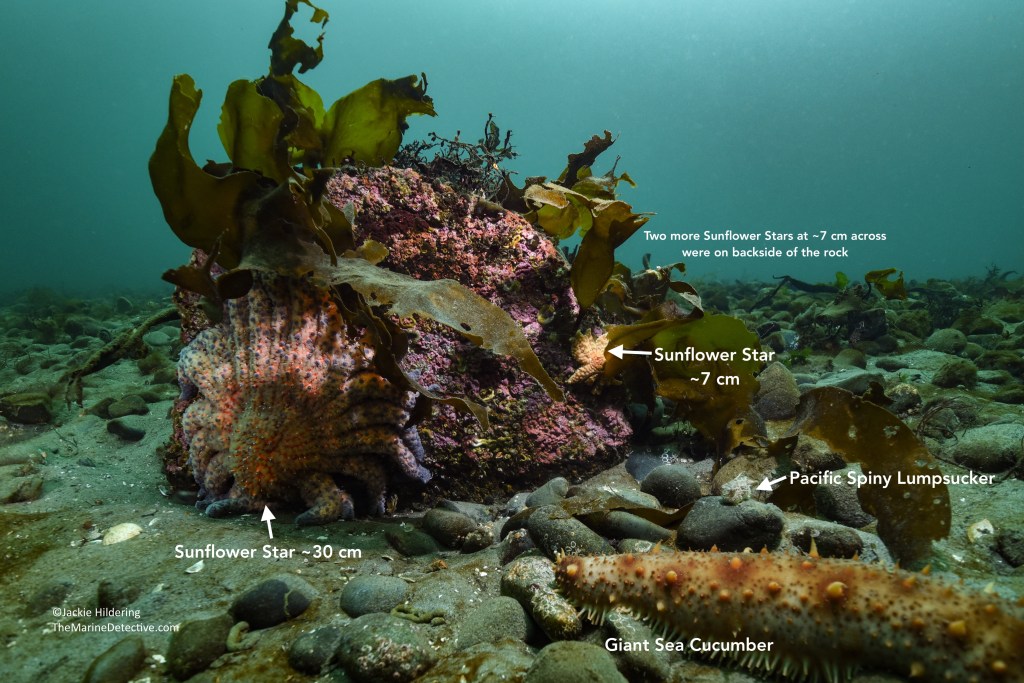

See them?

The Sunflower Stars AND the Pacific Spiny Lumpsucker?

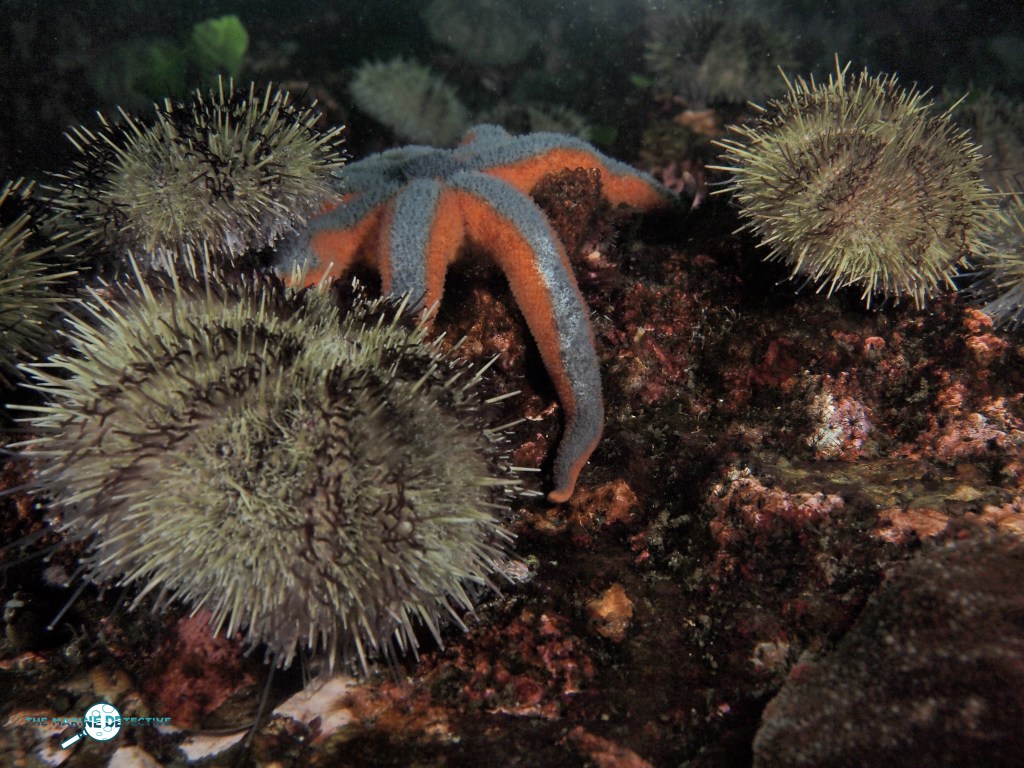

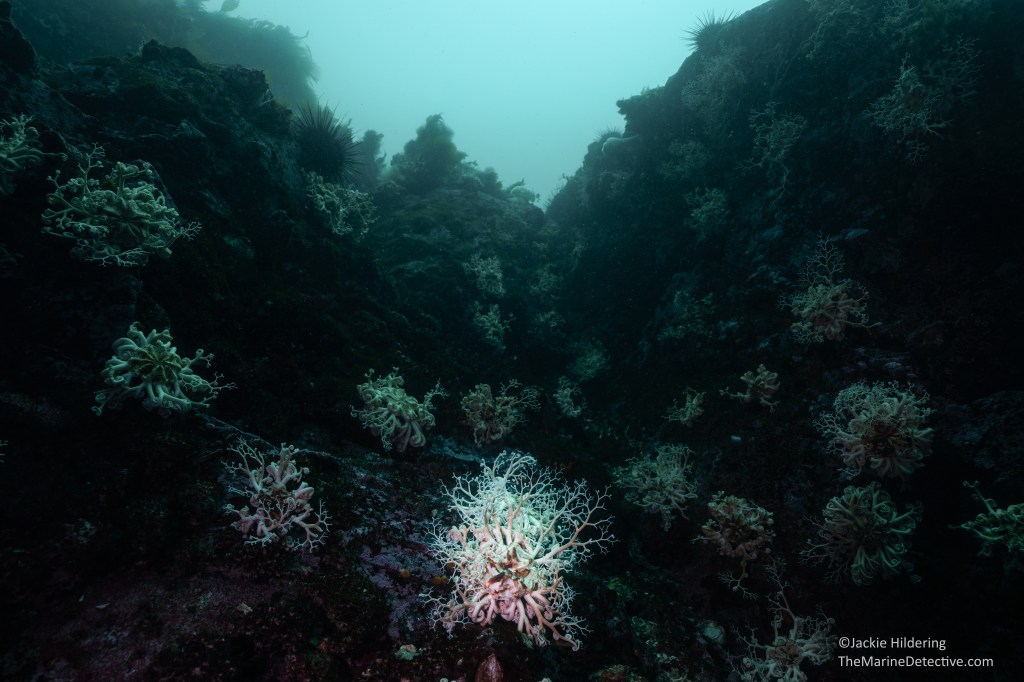

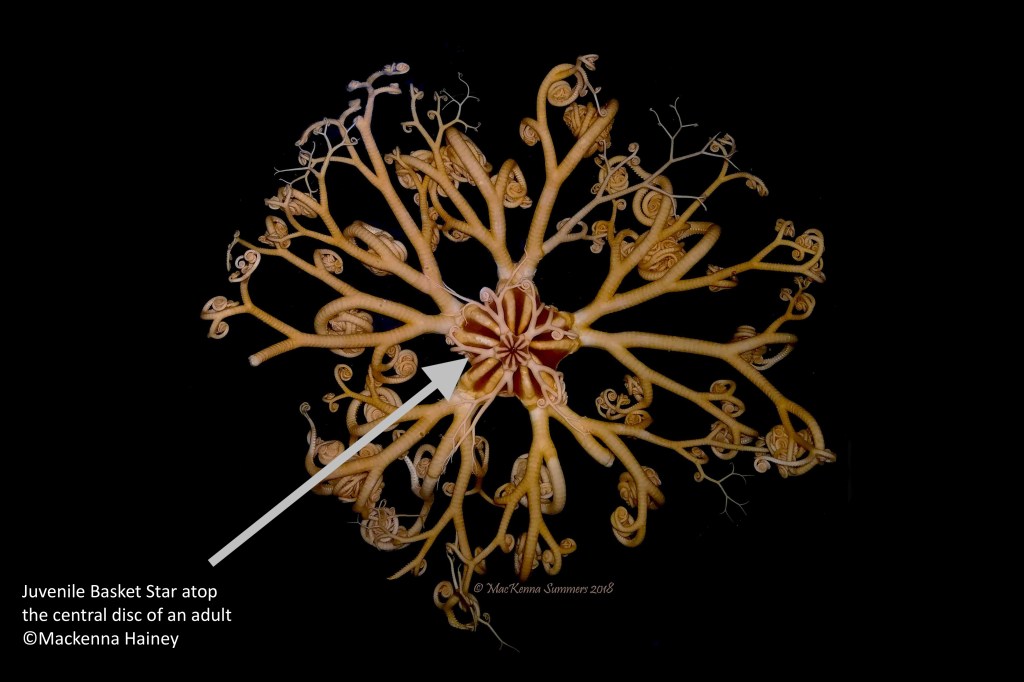

It brought a lump to my throat to see both these species at the same time. The Pacific Spiny Lumpsucker because this species is so cryptic and extraordinarily adapted (please read more about them in my blog “Pacific Spiny Lumpsucker – the fish, the disc, the marvel”). The Sunflower Stars because they are in such trouble due to Sea Star Wasting Disease. Sunflower Stars (Pycnopodia helianthoides) are the biggest sea star species in the world at up to 1 metre across.

But, somehow the conditions are such at this location that some adults appear to be surviving. I regularly document “waves” of juveniles but have seen so very few large ones since the onset of Sea Star Wasting Disease (SSWD) in 2013. I report all Sunflower Star sightings to researchers.

We would document thirteen Sunflower Stars during this dive – four at around seven cm across and nine at over 20 cm across.

And with that lump in my throat, I thought of sharing the photos of the Sunflower Stars with you and what the reaction might be. When I share photos of Sunflower Stars, some reactions suggest that I am diluting concern about them rather than educating about their plight and how this is believed to be related to a changing climate (which means there are common, and well known solutions that benefit life on earth).

Yes, there is hope. There certainly is. But, as I find myself stating and feeling so often, hope without action is paralysis. I recently came across the following quote which captures this so powerfully:

“People speak of hope as if it is this delicate, ephemeral thing made of whispers and spider’s webs. It’s not. Hope has dirt on her face, blood on her knuckles, the grit of the cobblestones in her hair, and just spat out a tooth as she rises for another go.” Source Matthew @CrowsFault on X

So here’s to the action that is Hope in all her power – for the stars, the lumpsuckers, and for all of us too.

The photos below show more Sunflower Stars documented on this dive, and how shallow some were. Please see the additional text below for details about the plight of Sunflower Stars.

February 16, 2026 ©Jackie Hildering.

Survivors

The text below is from my December 31, 2025 blog “Survivors” providing detail about the plight of Sunflower Stars and why, tragically, it is has become exceptional to see them (especially large individuals). The Sunflower Stars documented in the photos are from the same location as those in the above photos. Yes, some of them may be the same individuals. 💙

Why Does It Matter?

Sunflower Stars are the world’s largest sea star species at up to 1 metre across (Pycnopodia helianthoides). Before 2013, were you to look down from a dock in BC and Washington, you would likely see them . . . icons of our coast, common giants, and often what children would draw in seascapes.

That is no more.

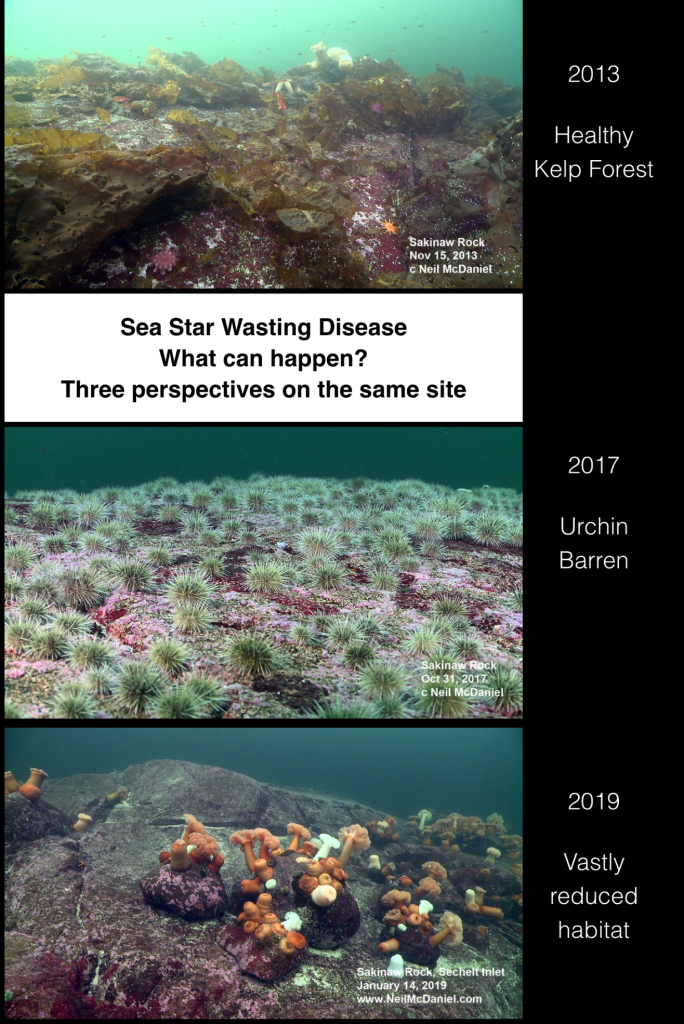

What happened to 20 sea star species in the Northeast Pacific Ocean has been referenced as “the largest epidemic ever recorded in a wild marine species.” Sunflower Stars were the most impacted and there are far-reaching impacts due to their ecological role.

Still many people do not know about their plight despite over 12 years of disease (and a horrific progression of symptoms). You can bet that if a whole lot of Sea Otters (which have similar ecological roles) died there would have been almighty public outcry. But this happened below the surface, in the dark, to species without eyes and fur.

What Happened?

Sea Star Wasting Disease (SSWD) began in 2013 and yes, recently Canadian researchers concluded what the pathogen / causative agent is. It’s the bacterium Vibrio pectenicida. But of course this does not mean that Wasting Disease is “solved”.

Why would this bacterium be able to have the impact it has? What changed?

From the research by Prentice et al. (2025) “Vibrio spp. have been coined ‘the microbial barometer of climate change’, because of the increasing prevalence of pathogenic species associated with warming water temperatures. Given that existing evidence indicates a relationship between increasing seawater temperature and SSWD incidence . . . ”

Where Are Things at Now?

In May 2025, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) recommended to the Government of Canada that Sunflower Stars be protected as an endangered species under Canada’s Species at Risk Act. It can be years before there is a decision.

This is not only important in Canada but the survivors in BC might be a reservoir for Washington State too where things appear to be even worse for the species.

What To Do?

Celebrate survivors – yes. Know that the plight of Sunflower Stars is not an additional problem. SSWD is a symptom of the same changes that impact our own species which means, there are common solutions regarding energy use, how we vote, and consumerism generally.

If you have read to this point in the blog, you are particularly important. You clearly care about life below the surface, in the dark. Help others know the importance of this coast. Help work against “ocean blindness” where the cold, dark waters full of plankton are devalued because it is more difficult to see the life living there. (Warm, clear waters are often perceived to be “better” because you can see far more easily see below the surface. But, if you can see through the water, there is far, far less plankton – the fuel of the marine food web.)

Children should know Sunflower Stars and their place on this glorious coast.

Since the onset of SSWD in 2013, I have tracked research and developments at this link. Includes where to report sightings.

All photos near northeastern Vancouver Island in the traditional territories of the Kwakwakw’akw. ©Jackie Hildering @The Marine Detective. Dive buddies on the dives referenced here: Janice Crook, John Congden and Ruxton Pitt.