Twelve Minutes With a Giant

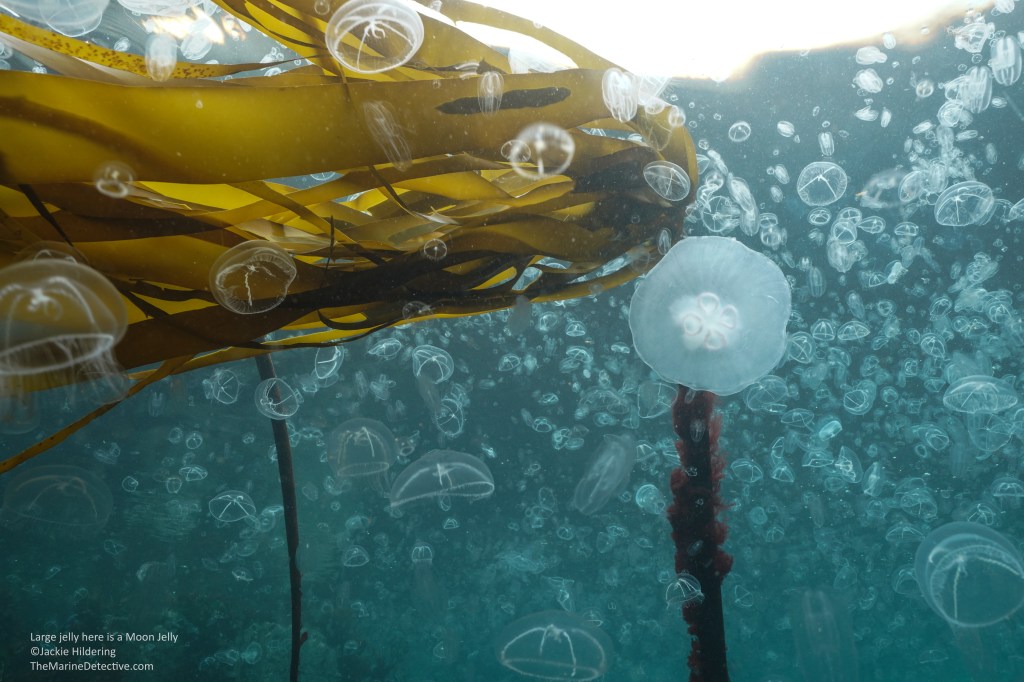

In April, there were quite a few Egg Yolk Jellies around northeast Vancouver Island. I dedicated one dive to trying to find at least one and watch it for a while. You never know what you’ll learn from a species that has survived on Earth for ~500 million years.

Egg Yolk Jellies are also known as Fried Egg Jellies. Gee, I wonder how this species got their common names? 😉 Their scientific name is Phacellophora camtschatica.

They are big at up to 60 cm across the bell. But that’s no where near as big as the other common giant jelly species off our coast, the Lion’s Mane Jelly. They can be 2.5 m across the bell (the bigger Lion’s Mane Jellies are usually not near the coast).

The yellow centres in Egg Yolk Jellies are the gonads. They can be much lighter coloured than the individuals you see here. Egg Yolk Jellies have 16 large lobes that alternate with much smaller lobe-like structures giving the bell a scalloped edge. Each lobe has clusters of up to 25 tentacles making for up to 400 tentacles (25 x 16) and they can be 6 metres long.

I was more than 30 minutes into the dive when I saw the white, slow pulsing through the soup of plankton. The jelly was swimming in my direction. I swam toward the jelly.

For twelve minutes, I watched, photographed, and learned.

I saw how the tentacles became longer and that the jelly stopped pulsing. Motionless in the water column, the tentacles spread out like a net. See that in the series of photos below?

I don’t think there was a “catch” (they feed on zooplankton, including ctenophores and other jellies). Had there been, the tentacles with the prey would have moved toward the jelly’s mouth.

I now have a much better appreciation for how they are not “passively planktonic”. They are active swimmers responding to cues in the environment. Moriarty et al., 2012 used acoustic transmitters to tag them and noted differences in swimming speed and vertical migration dependent on time of day and tidal cycle.

Jellies have sensory structures called rhopalia.

From Rebecca Helm, 2018:

Each ropalium . . . is packed with microscopic crystals at its tip. These crystals help the jelly sense up and down, by bending in the direction of gravity, similar to our inner ear. They also have a small pigment spot, which likely helps the jelly sense basic light and dark. So far, we’ve got an animal that can tell which way it’s pointing in space, and see rough light and shadow. Next we’ve got a few mystery structures, like the little bonnet-like structure surrounding the rhopalium above, which may act like a jelly nose, helping it sense chemicals in the water . . . Each rhopalium also acts like a pacemaker, helping coordinate jelly movement, similar to the way our cerebellum coordinates ours.”

And you thought they were just “going with the flow”. 💙

All photos in the above series are of the same individual.

April 19, 2025 north of Port Hardy in the Traditional Territories of the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw (the Kwak̕wala-speaking Peoples). ©Jackie Hildering.

For more information about the diversity of jellies on our coast, see my previous blog post “Gob Smacked” at this link. From that blog:

Lion’s Mane Jellies and Egg Yolk Jellies. are the only two common jelly species in our waters that can create a sting that irritates human skin, even when the jellies are dead. The stinging cells (nematocysts) work even when the jelly is dead or you get a severed tentacle drifting by your face. The sting from a Lion’s Mane Jelly is reported to be worst than that of an Egg Yolk Jelly.

I’ve been stung by both and clearly it’s not been enough to deter me from striving to get photos of them. But if you have far more skin exposed or are a fisher grabbing nets with many of the tentacles wrapped in them, it is reported to be very uncomfortable.

The solution to the irritation is vinegar (acid), meat tenderizer (enzyme) and I know that many fishers swear by Pacific canned milk as well. Research puts forward that vinegar is the only real solution and that urine does not work at all.

Sources:

- JellyBiologist.com – How do jellyfish perceive the world?

- MarineBio.org – Fried Egg Jellyfishes

- Moriarty P, Andrews K, Harvey C, Kawase M. 2012. Vertical and horizontal movement patterns of scyphozoan jellyfish in a fjord-like estuary. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 455:1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.3354/meps09783

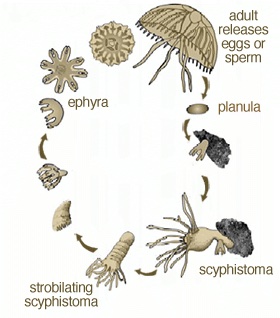

There is alternation between a polyp with asexual reproduction and a medusa with sexual reproduction.

I have not been able to find specifics about the lifespan of Egg Yolk Jellies other than “species can have a lifespan of several years.” I have questions about why we saw quite a few dead on the ocean bottom around the same time in different locations, and what that may suggest about the lifecycle.