Nudibranch named for Dr. Sylvia Earle

I am very late to this party. Back in 2020, a nudibranch was named in honour of Dr. Sylvia Earle when there was reclassification of the Yellow-margin Dorid and the research was published by Korshunova et al.

There is now Sylvia Earle’s Cadlina (Cadlina sylviaearleae).

Despite my great admiration for Dr. Earle and for sea slugs, I did not realize these two had come together until I recently posted one of the photos you see below. Karolle Wall very kindly let me know that this was no longer a Yellow-margin Dorid (Cadlina luteomarginata).

What follows is focused on the reclassification and how difficult it is to discern these species from external characteristics. If you have an electron microscope, it will be easier. 😉 You would be able to see the differences in the radula (tooth-like structures).

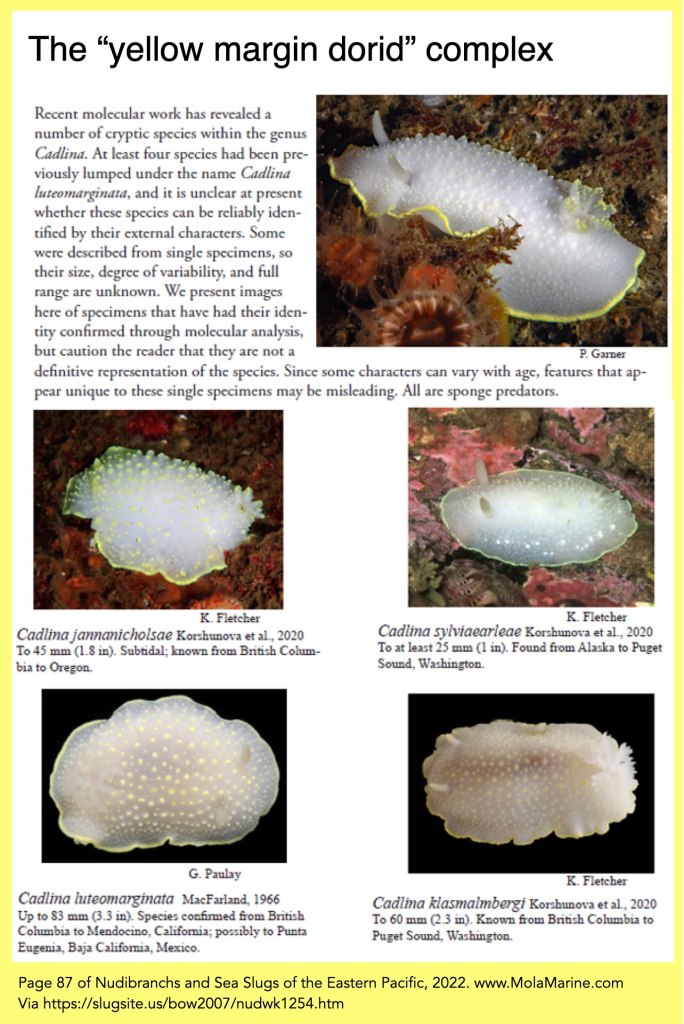

What was historically Cadlina luteomarginata is now at least four described “yellow-margin dorid” species. Sylvia Earle’s Cadalina is described as a sister species to Cadlina luteomarginata. What Karolle pointed out as a helpful discerning characteristic is the space between those distinctive tubercles on the nudibranch’s side.

From Korshunova et al., 2020

“Until recently, C. luteomarginata has been considered a single species with a whitish notum and yellow marginal line with a broad range in the north-eastern Pacific from Alaska to California (e.g. MacFarland, 1966; Behrens, 1991; Behrens & Hermosillo, 2005). Present integrative morphological and molecular analysis reveals that there is considerable hidden diversity among Cadlina from the north-eastern Pacific.”

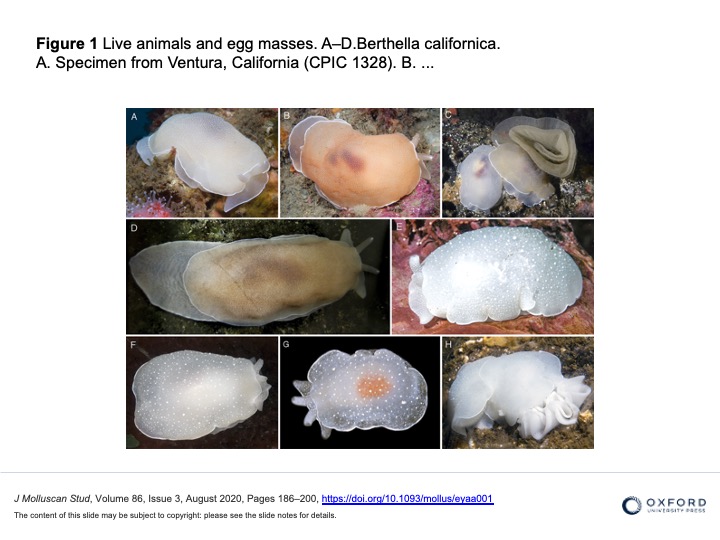

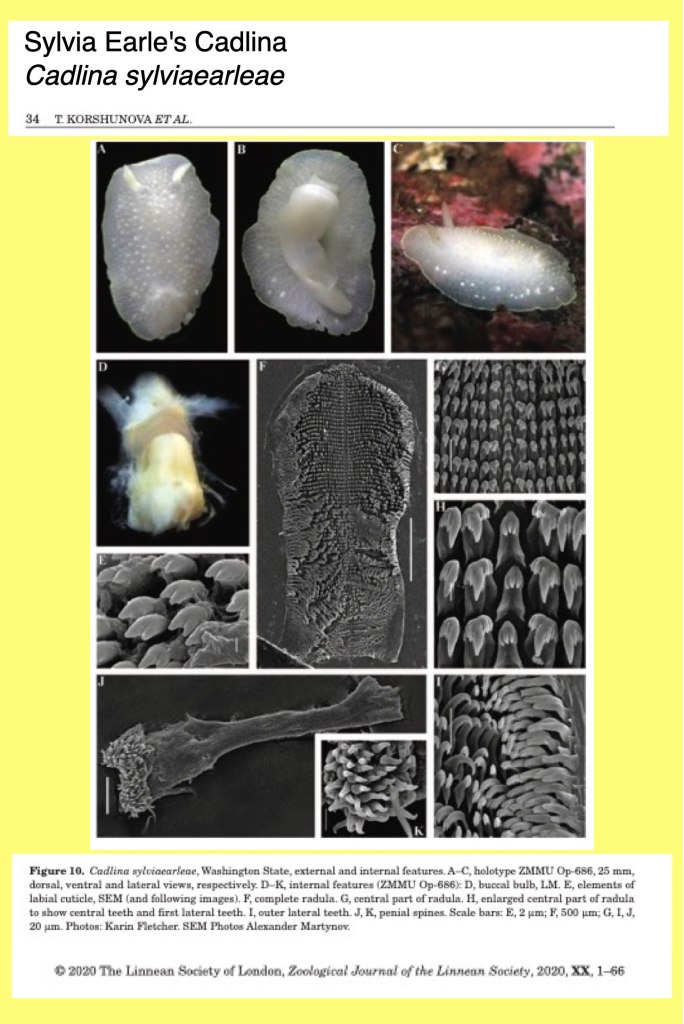

Sylvia Earle’s Cadalina (Cadlina sylviaearleae)

“Opaque whitish, with some small dorsal tubercles tipped with yellow. Rhinophores with slight yellow tint. Gills are semitransparent white, similar to ground colour . . . differs both molecularly and in a number of morphological features from all other described Cadlina species.” (Korshunova et al., 2020).

Size to at least 2,5 cm. “Known from British Columbia to Oregon”. (Behrens et al., 2022)

Differences with the Yellow-margin Dorid (Cadlina luteomarginata) as originally described by MacFarland (1905, 1966)

“Considerably less tuberculated notum [upper surface of the body], more weakly developed yellow line around notum and by patterns of the radula”. (Korshunova et al., 2020).

Size up to 8.3 cm. “Species confirmed from British Columbia to Mendocino, California, possibly to Punta Eugenia, Baja California” (Behrens et al., 2022).

More from Nudibranchs and Sea Slugs of the Eastern Pacific, 2022:

“Recent molecular analysis work has revealed a number of cryptic species with the genus Cadlina. At least four species have been previously lumped under the name Cadlina luteomarginata and it is unclear at present whether these species can be reliably identified by their external characteristics . . . All are sponge predators.”

Personal note: Reading about these species and writing this blog took me over 3 hours. Why do this? Time evaporates and I get lost for a while in science and the sea. I suppose that’s enough reason. A great bonus would be if this is of use to others too.

Sources:

Behrens, David & Fletcher, Karin & Hermosillo, Alicia & Jensen, Gregory. (2022). Nudibranchs and Sea Slugs of the Eastern Pacific.

Behrens, David. (2022). Slug Site.

Korshunova, Tatiana & Fletcher, Karin & Picton, Bernard & Lundin, Kennet & Kashio, Sho & Sanamyan, Nadezhda & Sanamyan, Karen & Padula, Vinicius & Schroedl, Michael & Martynov, Alexander. (2020). The Emperor’s Cadlina, hidden diversity and gill cavity evolution: new insights for the taxonomy and phylogeny of dorid nudibranchs (Mollusca: Gastropoda). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz126.

Olson, Danielle (2025). Meet Sylvia Earle, the Trailblazing Marine Biologist Who Has Spent Her Career Giving Algae Their Long-Deserved Due. Smithsonian Magazine.