Sharks Among Us – The Brown Cat Shark

Here’s a mystery shared (and solved) by Farlyn Campbell.

This was found in May of 2018 north of Port Hardy.

Photo: Jared Towers. Brown Cat Shark egg case found on May 30, 2018 near Doyle Island off NE Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Found by Jared and Farlyn when they came upon a rope with buoy drifting in the ocean. They removed the rope due to its potential to entangle animals and of course placed the egg case back in the ocean.

It’s the egg case of a Brown Cat Shark (Apristurus brunneus) with an embryo developing inside and it’s mind-blowing how long it takes before it hatches. Read on!

The Brown Cat Shark is a common species of shark off British Columbia’s coast but, here we go again . . . very little is known about it.

Most sharks (about 60%) have “viviparous” reproduction where the young develop inside the female and hatch out when fully developed.

However, Brown Cat Sharks have “oviparous” reproduction where the eggs hatch outside the body of the female. The embryo develops inside the egg, feeding on the yolk. Yes, this is how birds develop too. The egg cases of oviparous sharks are not shelled however, as you can see above. They have distinct shapes per species but all have this tough “leathery” membrane. The egg cases are also known as a “mermaid’s purses”. (See the end of this blog for further information on reproductive strategies in sharks).

Female Brown Cat Sharks lay one egg case at a time that contains a single embryo. Each egg case is around 5 cm long and 2.5 cm wide. In the case of Brown Cat Sharks, the embryo develops inside for more than 2 years! In our cold waters, maximum known incubation period is 27 months. The size of the hatched pup is 7 to 9 cm. (Source: Love). Development is shorter where temperature is warmer.

The distinctive “tendrils” on the egg cases of Brown Cat Sharks are believed to help anchor them to hard surfaces.

In British Columbia, the females carry (and deposit) between 1 to 16 mature eggs most often between February and August. (Source: Love and McFarlane). Further to the south in their range, they females apparently lay egg cases year round.

Little is known about what feeds on the egg cases but bore holes suggest that gastropods like whelks drill into them.

Brown Cat Shark – Details

See below for more information on the 16 species of shark known to be off the coast of BC. Image source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Sharks of British Columbia.

Cat sharks (Scyliorhinidae) are the most diverse and largest family of living sharks. There are ~157 species worldwide. Their common name may be in reference to their cat-like eyes.

Brown Cat Sharks are harmless to humans. They feed on small true shrimps, pelagic red crabs, euphausiids, mysid shrimps, isopods, squids, and small fishes (Source: Love) Off the coast of BC, maximum documented size for the Brown Cat Shark is 70.4 cm for males and 65.1 cm for females (Source: Wallace et al).

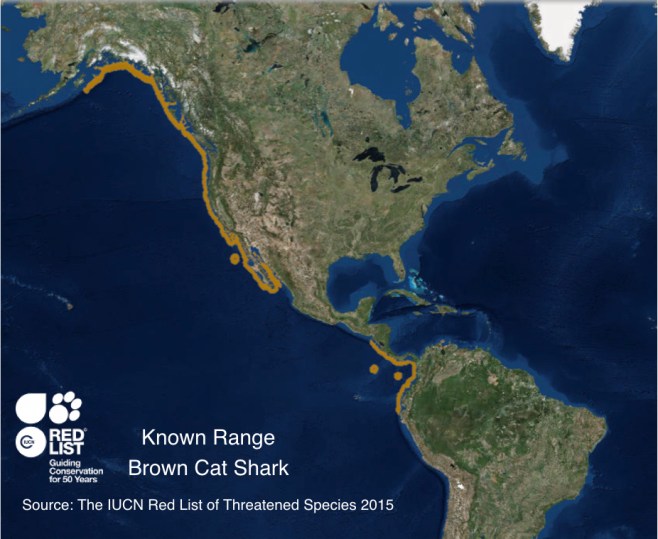

The Brown Cat Shark is a cold water species, found in waters from 5 to 8°C in the Eastern Pacific. They appear to be most common from British Columbia to northern Baja California, Mexico with their known range extending from Alaska to Columbia in South America. They are probably also off Panama, Ecuador, and Peru.

Known global range of the Brown Cat Shark. Source: IUCN.

Brown Cat Sharks are a deep-dwelling species, often over mud/sand and on the outer continental shelf. Known depth range is 33 to 1,298 m. They are most often found at depths of 137 to 360 m in the cold waters off the coast of British Columbia. Where it is warmer, they are likely to be deeper e.g. most often at depths of 656 – 932 m off southern California (Source: IUCN).

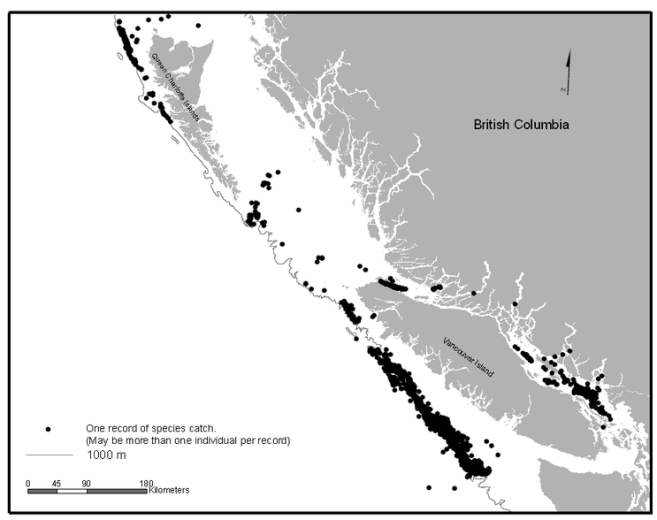

Distribution of Brown Cat Shark off the west coast of Canada from 1965 to 2007. Source: McFarlane.

As aforementioned, the Brown Cat Shark is one of the most common shark species off the coast of BC but so little is known about it and there have not been the recommended efforts to fill knowledge gaps.

Risks to the Brown Cat Shark include that it is commonly taken as bycatch in deepwater trawl fisheries (Source: IUCN). The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) reported in April 2007 that there was not enough information known about the species to evaluate how at risk it was = Data Deficient. MarFarlane et al, 2010 determined that the Brown Cat Shark was among those shark species off the coast of BC that was a high priority for further study. This has not yet happened. Reportedly, there are no management measures currently in place for the Brown Cat Shark anywhere in the world (Source: IUCN).

Shark Reproduction

Unlike most fish, sharks have internal fertilization, where the eggs are fertilized inside the female’s body. The males have reproductive structures known as “claspers” (modified parts of the pelvic fins). Claspers are appropriately named as, not only do they transport sperm into the female’s oviduct, they also anchor into the female.

Most sharks are viviparous, giving birth to fully developed young. As mentioned above, Brown Cat Sharks are not. They are oviparous.

Shark egg development modes in further detail:

Oviparity = egg-laying. After fertilization, the egg cases are deposited into the ocean. There is no development of the embryo inside the female. The embryo develops inside the egg case feeding on the yolk. The only oviparous shark off the coast of BC is the Brown Cat Shark. The skates off our coast are oviparous as is the Spotted Ratfish. (See the image at the end of this blog contrasting their egg cases / mermaid’s purses).

Viviparity = after fertilization, the embryo develops inside the mother and the young are fully developed when born. There are two types of viviparity:

- Placental viviparity:

We humans and most other mammals and reptiles also developed via placental viviparity. The embryos develop inside the mother, attached to her placenta (in the case of viviparous sharks, the umbilical cord is between the pectoral fins). Through the placenta, the mother’s blood delivers nutrients and oxygen to the embryo and waste is transported away. Examples of sharks off the coast of BC who develop by placental viviparity: Sixgill Shark, Sevengill Shark, Blue Shark, Pacific Sleeper Shark, Spiny dogfish. - Aplacental viviparity (Ovoviviparity): In this case, there is no placenta to nourish the embryo. The young develop inside the eggs while in the mother’s oviduct and are born fully developed. They feed from the yolk as well as from glands in the oviduct walls (there are varied ways this “uterine milk” is delivered). The embryos hatch into the oviduct and finish development feeding from gland secretions and unfertilized eggs (known as being “oviphagous”). In some species, the first pup to hatch eats their developing siblings. This is referenced as being “embryophagic” or “adelphophagic” (translates literally into “eating one’s brother”) and is not known in any other animals other than some species of sharks. You can imagine that final litter size is small in sharks with this “intrauterine cannibalism”. Examples of sharks off the coast of BC who develop by aplacental viviparity are: Tope (Soupfin) Shark, Pacific Angel Shark, Spiny Dogfish, Common Thresher Shark, Bigeye Thresher Shark, Shortfin Mako Shark, Basking Shark and Salmon Shark. Those whose embryo development is known to include embryophagy are the: Common Thresher Shark, Bigeye Thresher Shark, Shortfin Mako Shark, Basking Shark and Salmon Shark (Source: Elasmo-Research).

Sharks off the Coast of British Columbia

Image source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Sharks of British Columbia. Click to enlarge.

In BC waters there are 16 species of shark from 11 families.

Brown Cat Shark (Apristurus brunneus)

Spiny Dogfish (Squalus acanthias)

Sevengill Shark (Notorynchus cepedianus)

Salmon Shark (Lamna ditropis)

Blue Shark (Prionace glauca)

Pacific Sleeper Shark (Somniosus pacificus)

Common Thresher Shark (Alopias vulpinus) ICUN status: Vulnerable

Bigeye Thresher Shark (Alopias superciliosus) ICUN status: Vulnerable

Shortfin Mako Shark (Isurus oxyrinchus) ICUN status: Endangered

Green-Eye Shark (Etmopterus villosus)

Protected under Canada’s Species at Risk Act:

Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus) – Endangered (and ICUN status: Vulnerable)

Sixgill Shark (Hexanchus griseus) – of Special Concern

Tope (or Soupfin) Shark (Galeorhinus galeus) – of Special Concern (and ICUN status: Vulnerable)

Incidental:

Great White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias) ICUN status: Vulnerable

Hammerhead Shark – 2 known sightings up to 2016 (Source: Royal BC Museum)

Pacific Angel Shark – 1 known sighting up to 2016 (Squatina californica) ICUN status: Near Threatened

Contrast of egg cases commonly found along coastal British Columbia. Only the Big Skate can have more than one embryo per egg case. Reported to be up to a maximum of 7 embryos but more often 3 to 4.

Sources:

- De Maddalena, Alessandro & Preti, Antonella & Polansky, Tarik. (2007). Sharks of the Pacific Northwest. Including Oregon, Washington, British Columbia and Alaska.

- Elasmo-Research.org. From Here to Maternity.

- Enchanted Learning. Shark Reproduction.

- Fishbase. Brown catshark and Family Scyliorhinidae.

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Sharks of British Columbia.

- Flammang, Brooke E. et al. “Reproductive biology of deep-sea catsharks (Chondrichthyes: Scyliorhinidae) in the eastern North Pacific.” Environmental Biology of Fishes 81 (2006): 35-49.

- Huveneers, C., Duffy, C.A.J., Cordova, J. & Ebert, D.A. 2015. Apristurus brunneus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T44209A80671448.

- Love, M. 2012. Certainly More Than You Want to Know About The Fishes of The Pacific Coast—A Postmodern Experience, Really Big Press, Santa Barbara, California.

- McFarlane, Gordon & Mcphie, Romney & King, Jacquelynne. (2010). Distribution and Life History Parameters of Elasmobranch Species in British Columbia Waters.

- Royal BC Museum. A new Shark for BC – Pacific Angel Shark

- Wallace, S., McFarlane, G.A. and King, J.R. 2006b. COSEWIC Status report on brown cat shark Apristurus brunneus prepared for Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 20 p