How to Love the Ocean – Daily Actions for Future Generations

Here’s a whole lot of information, and entertainment, about ocean education.

It includes:

- Ocean Inspiration (why it is so important to teach about the ocean)

- Action for the Ocean (detail on the many ways we can reduce impacts); and

- Guidelines for Beach Walks.

- My Ocean’s Day presentation on Ocean Wonders.

Ocean Inspiration

Why is it so important to educate and help others love the ocean?

Chances are that if you have the interest and motivation to read this, you already have that knowledge. May the following then provide you with affirmed purpose and inspiration.

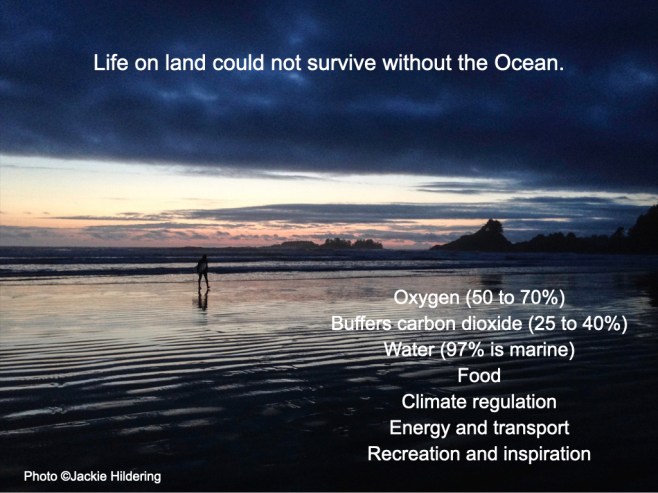

The ocean is the life-sustaining force on the planet. It is where life began. The ocean’s algae produce at least 50% of the world’s oxygen, buffering carbon dioxide in the process. As water cycles around, over 90% at any time is ocean. The ocean is the largest surface on earth, whereby it has a significant impact on climate regulation. The ocean is also a source of food, energy, inspiration, transportation, and healing.

Human psychology so often puts a divide between land and sea. There is not enough understanding that life on land cannot survive without the ocean, no matter how far you are from her shores. As a result of this perceived divide, assaults upon the ocean include persistent organic pollutants, agricultural runoff, warming and ocean acidification, disease organisms, and plastics and further marine debris. Consequently, the ocean so often testifies to socio-environmental problems first.

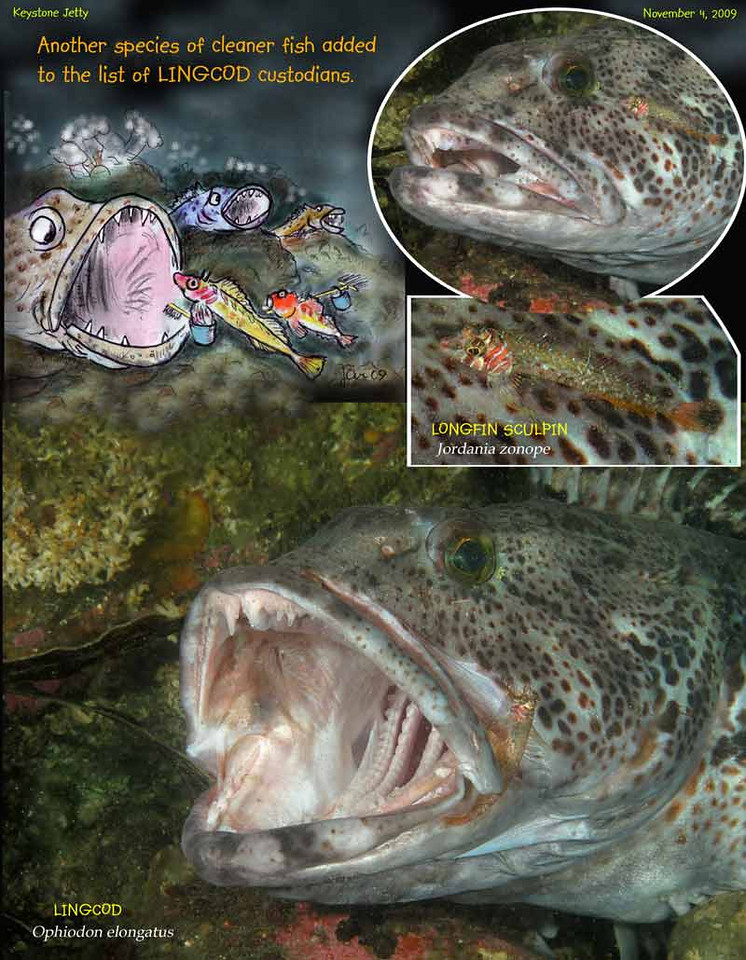

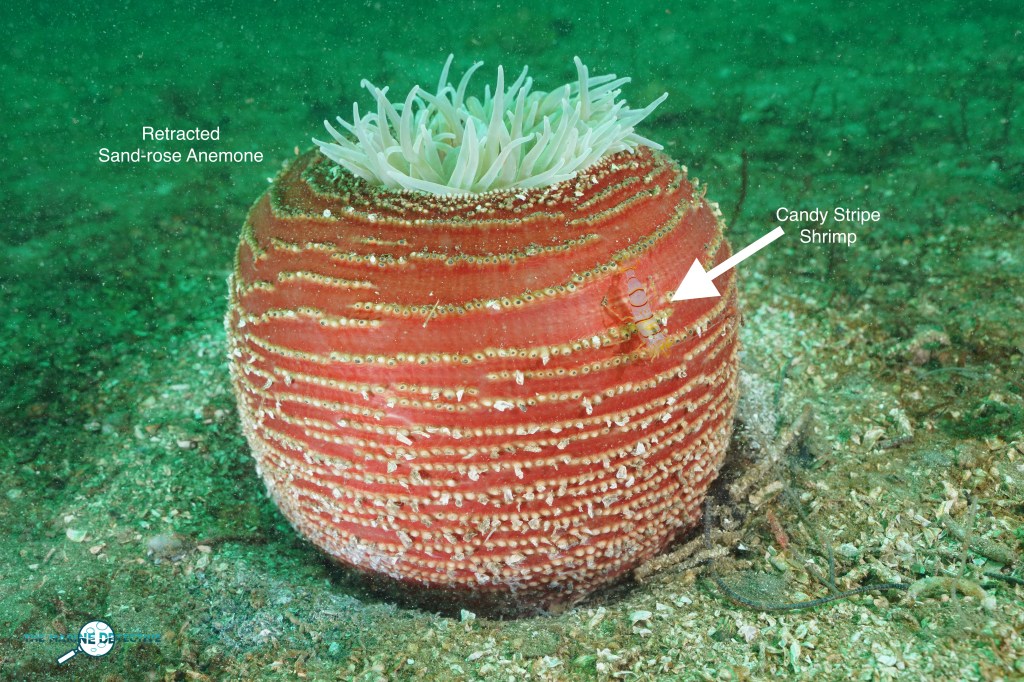

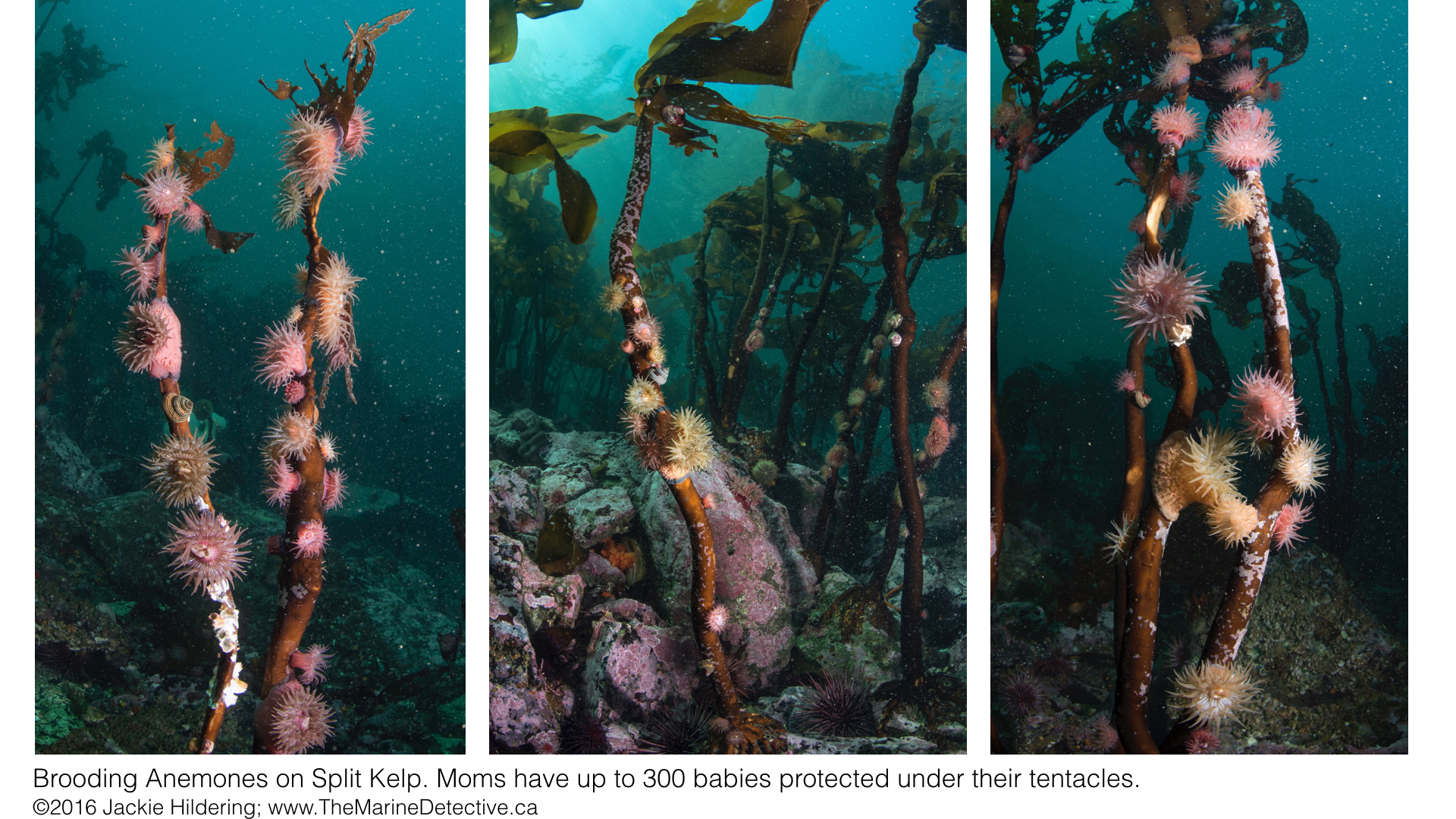

This “ocean blindness” is especially true of the perception of dark oceans where the rich plankton soup means we cannot see the marine life easily. Thereby, many of us form biases to thinking there is more life in warmer waters with less plankton. This is exactly backwards. Less plankton means there is less food at the bottom of the food web. Thereby, if you can easily see through water, there is less life in it.

This bias and blindness is exacerbated because, so often, the imagery we are fed in everything from documentaries, to children’s books and movies, is of life in warmer seas. If we do not know how extraordinary our marine neighbours are, and how important the ocean is, how can we be the teachers, parents and voters we need to be?

By helping others love the ocean, you are not only helping marine life, you are helping the future of our own species as well.

Power to you.

Ocean Action

First there’s a summary. Then, there’s depth.

SUMMARY

1. Learn about the ocean. Enjoy the ocean.

It is especially important to learn about species that live closest. No matter how far away the ocean is, we are connected to the life there through the cycling of water.

2. Care, knowing how important the ocean is to life on land and how amazing our marine neighbours are. We need to be especially careful because we still know so little about life in the ocean which means we could make big mistakes.

3. Use less because it is about gain, not loss. By making sure there is less garbage (includes less disposables and less consumerism) and less bad chemicals, there is less pollution in the ocean AND on land. By saving energy and helping use less oil and gas (fossil fuels), there is less change in temperature and climate. By using less water, less chemicals are added to the water at the sewage treatment plant. What cannot be biodegraded (rot away) or physically filtered out of the water at the treatment plant, will end in the ocean.

4. Teach and share with others about the importance of the Ocean and how easy it is to do good things that help the ocean AND ourselves.

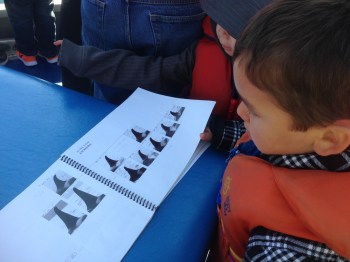

Children finding fish in one of my Find the Fish books.

MORE DEPTH

1. No Problems Without Solutions

Yes, it is important for students to know of environmental problems. But, there is the potential of creating overwhelm, fear / paralysis, disconnect and the perception that nature and/or the ocean is sick. It is vital to ensure that solutions are provided; that those doing the teaching are modelling those solutions; and that the common denominators between socio-environmental problems are made clear i.e. most problems have the same causes whereby there are the same solutions. Examples are the connection between Sea Star Wasting Disease in Sunflower Stars and warming seas; over-harvesting being related to inequality in the world and the lack of precaution in favour of short-term economic gain; and plastic pollution being the result of consumerism, overuse of disposables, and disconnect with the environment.

2. Connect / Learn / Respect

No matter how far you are from the ocean, you can connect to the ocean. I emphasize again the value of prioritizing learning about the most local ocean (and species) so that the biases and blindness I referenced above are not exacerbated. For example, turtles are amazing and engaging but what is most valuable for Canadians is connecting to the Leatherback Turtles that belong off both Canada’s east and west coasts.

Understanding of the water cycle is such an effective way to connect to the ocean from any distance i.e. the ocean is on top of mountains as snow, it flows through rivers and groundwater, and it comes out of the tap. Therefore it is impacted by what we do to water even when far away from the ocean. Including sewage treatment in the water cycle is of great value.

I find it helps to reference local marine life as “neighbours” as this suggests that we live together and are connected. Beach walks, if possible, certainly aid this if conducted as a study and with respect. Please see my guidelines for good beach walk practices below.

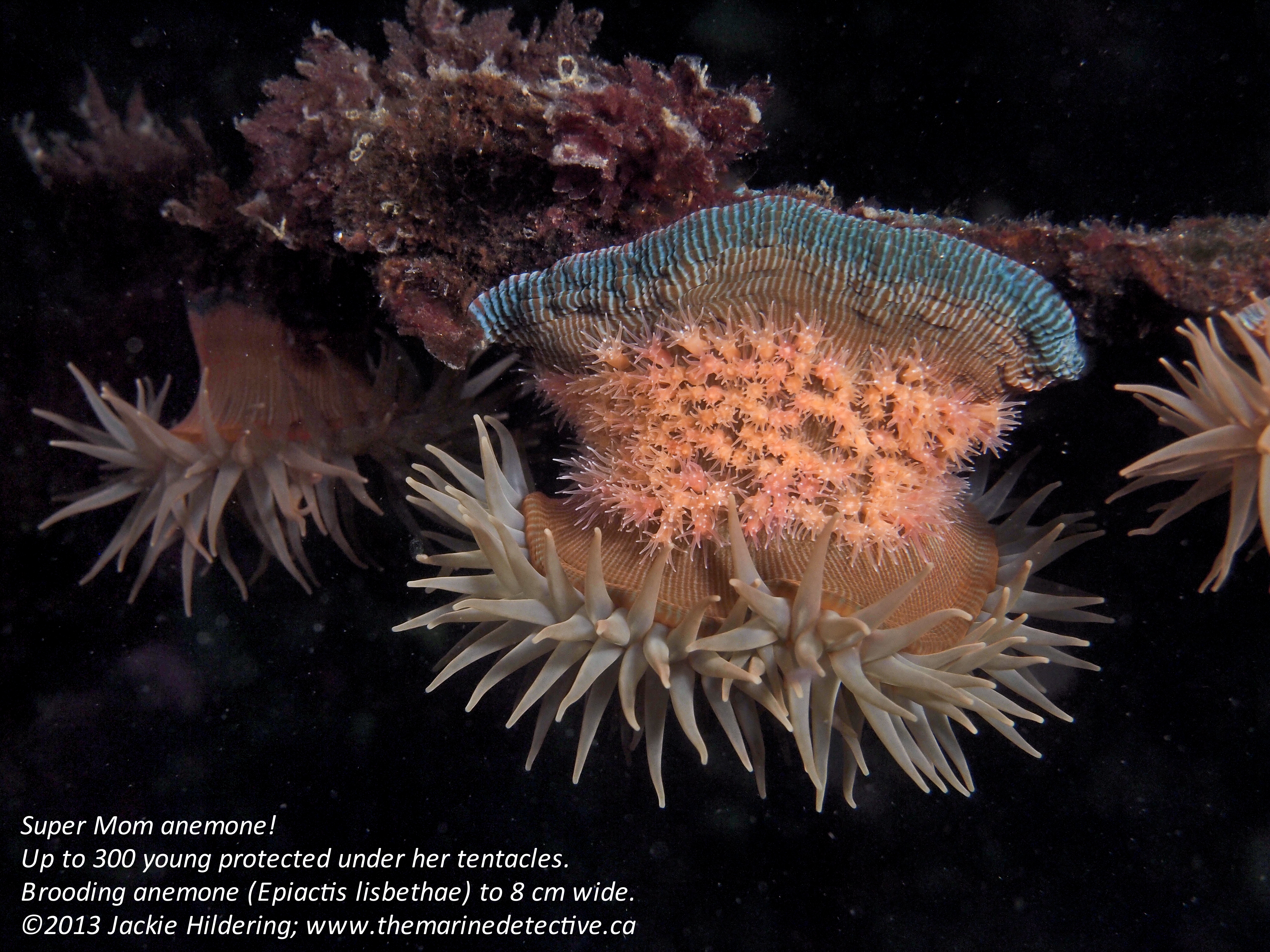

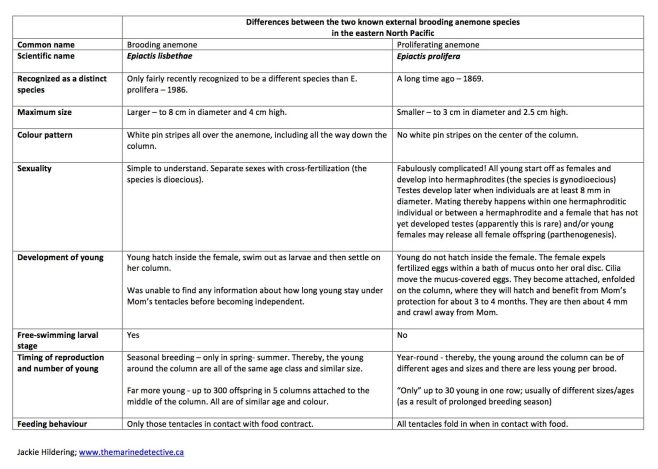

It is so valuable too to teach from a perspective of adaptations, allowing students to deduce why species look the way they do, live where they do, and/or behave as they do. This allows for the understanding that nature is not “random” but that organisms are connected, evolved, and have fulfilled niches to fit into the puzzle of life.

Please, do not limit learning to the species at the surface i.e. the charismatic marine megafauna like whales. To understand why there are these big animals, requires an understanding and valuing of the biodiversity and interconnectedness below the surface.

Please too do not encumber yourself with feeling you need to know a lot about marine species in order to aid love and action for the ocean. By not knowing, you give even more space for students to form connections and hypotheses about adaptations, and to own their knowledge. One of the most vital things in loving and learning about the ocean, is to emphasize how little is known about life in the ocean and, therefore, that it is essential to have the appropriate humility and precaution in how we “manage” the ocean.

3. Reduce

This is the single most important solution to reducing socio-environmental problems, including impacts to the ocean.

So many students believe that recycling is the best thing they can do (and our consumer paradigm of course favours this). It shows, in part, that understanding has been lost that the three “Rs” are a hierarchy. By far the most important is to REDUCE. Next is to re-use. And if reducing and reusing are not possible, then . . . recycle.

Reduce what?

It is very important to approach this from the perspective that reducing is not about loss, but about gain and that the following are also the solutions for so many other problems.

– Reduce the use of harmful chemicals that can flow or condense into the ocean. Which chemicals are bad? The easiest with younger students it to show the skull and crossbones on the label of products like bleach. Older students have curriculum content about pesticides and other persistent organic pollutants. It is valuable of course to discuss how the human-made bad chemicals are not essential and/or that there are alternatives that are not harmful.

– Reduce fossil fuel use because of the impacts on climate change. The ideal is to enable students to think in terms of carbon footprint and, thereby, to know how many ways we are empowered to reduce fossil fuel use in our every day actions and how smart and innovative we become when we care more.

Never too young to learn about animals as individuals.

– Reduce waste. This goes far beyond beach clean-ups. Understanding is needed of why there is so much garbage and how easily this can be solved when we learn and care. This includes using durable and reusable things, not buying so much, being aware of how much packaging things have and, here’s the BIGGY, to understand the difference between biodegradable and non-biodegradable. If something cannot rot away there is no “away”. It cannot be flushed “away” or thrown “away”. Non-biodegradable chemicals enter the water and food webs. Plastics that cannot rot will entangle, or get mistakenly eaten by animals, and/or break down into smaller pieces that enter the food web.

4. Empower

Sharing good news stories, especially of innovative and ethical thinking and technologies that create positive change, allows students to know about human social evolution, that we learn from our mistakes, and make huge steps forward when empowered with knowledge and caring. It will help make them feel there is space in the world for their ideas and that every generation learns from the ones before. It is tricky though to ensure that hope and human ingenuity are not perceived as exit strategies.

Empowerment too means providing students with the opportunity to participate in decision-making and respectful dialogue about practices and decisions made at home and at school. It will involve discussions about ethics and how we cannot be perfect. We have to use resources and make some garbage but can make decisions that reduce impacts. It invites critical thinking. It can lead to learning about who and what we support with our money and effort is like voting, and the importance of that.

Again, power to you. 💙

Below is my presentation on Ocean Wonders.

Black Prickleback father guarding eggs. Were he to be moved by those who think he does not have enough water, the eggs would be eaten by predators.

Good Beach Walk Practices Include:

No Taking and No Touching (with exceptions)

There are exceptions when you know for sure a species is hearty or truly in trouble. Hearty species like sea stars can gently be touched with one’s pinky. By using your little finger, you can’t apply much pressure and this very act instills greater understanding and respect in children for the life they are visiting and learning from. It is also the case, that what is one our hands, may not benefit other animals. I am sure there is heightened awareness of transmission of pathogens in our current COVID world

Collecting animals does not model respect (e.g. Shore Crabs). Even taking shells does not allow for the understanding that there are animals that will use these (e.g. hermit crab species) and that, as the shell breaks down, nutrients are returning to the Ocean. There are exceptions here too where a few “treasures” (non living) can be taken for further study.

Moving animals, even with the best of intentions, can lead to unintended consequences like displacing fish fathers from the eggs they were guarding. There are fish species that are very well-adapted to surviving with little water at low tide.

Another exception is, of course, that you DO want to remove garbage that you are sure IS garbage and that has not become habitat (has life living on it).

Another fabulous example of where the well-intentioned are not helping. These are not garbage. They are moonsnail egg collars. They are wondrous constructions to house and protect moonsnail embryos. There’s much more information about them in my blog at this link.

Rock Rules

Only lift rocks that you do not need to pivot and that you can put back very carefully. If you pivot big rocks, animals will rush to hide at the leverage point and will be crushed when you lower the rock.

A good rule is to only lift rocks smaller than your head, and that clearly have space under them (this means there are likely to be animals there and that you can better return the rock to its position). I have found it really helps to explain to children why life under a rock lives there and not on top of a rock (i.e. teaching about habitat). Children seem to understand well that lifting a rock is like lifting the roof off a human’s house.

Walk Carefully

This is not only for human safety but seaweed and Eelgrass are habitat to so many animals.

Barnacles too are living animals.

No Squealing and No YUCK!

This is negative and can perpetuate a physical reaction of disconnect and disrespect for the natural world. It is “rejection” and judgement of another organism being “wrong” rather than understanding the perfection of adaptations and evolution. Beach walks are about visiting organisms in their habitat and the gift of being able to learn that everything is the way it is for a reason. I find it helps to let children know, when about to lift a rock, that we are disrupting animals in their home so that we can learn and that, of course, the animals are going to be startled i.e. so they anticipate the potential of things like fish flopping about.

YES to pictures, learning and contributing to knowledge. 💙

Below, an exception to the rule. This Gumboot Chiton was upside down and could not have righted itself. They are tough organisms and provided a wonderful opportunity for students to feel how this is a living animal that responded to their gentle touch.

Related posts:

Find the Fish for Ocean Day (student activity)

More of my blog items on Ocean Inspiration and the importance of the Ocean.