Ky, Ky, Ky – Chitons!

I’ve wanted to write a blog about chitons for so long because, they are wondrous and . . . we need wonder.

If you are fortunate enough to live near the Ocean, chitons are there, on rocks right in the intertidal zone, descendent from ancestors that date back ~500 million years. Chitons are in fact referenced as living fossils since their body design has not changed significantly for more than 300 million years.

Other members of this class are found at great depth. There are about 1,000 species worldwide with 50 known to live in the range from Baja California, Mexico to the Aleutian Islands, Alaska.

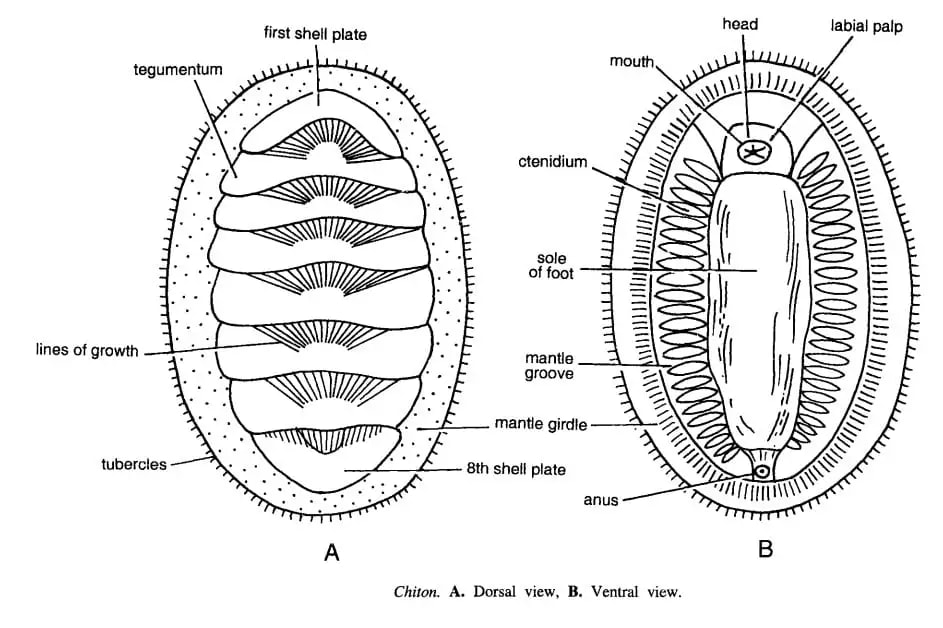

What makes them unique among molluscs (the soft-bodied invertebrates) is that while some molluscs have no shell (octopuses, squid and sea slugs); and some molluscs have one shell (snails, abalone and limpets); and some molluscs have two shells (clams and oysters) . . . chitons went their own way to all have EIGHT shells, known as plates.

This is reflected in the name of the class to which they belong – the “Polyplacophora” which translates into “many plates” in Greek. Oh and “chiton” also reflects that they have multiple shells. Chiton is Greek for “coat of mail”. Chiton is pronounced “ky-ton” by the way.

But all the preceding information about chitons is what you could read in a field book. Let me share the wonder of chitons with you as it has awakened in me, taking my appreciation far beyond the limits of drawings and words in biology textbooks.

Chitons are THIS.

And THIS

And THIS

And THIS

And THIS

Most chitons graze, scraping algae off rocks with their radula (see video at the end of this blog).

However, Veiled Chitons are carnivores! When an animal wanders under

their veil, this triggers the veil to drop and then . . . lunch.

You can see how quickly that happens in the video at the end of this blog.

By having eight plates and a band of muscle (the girdle) chitons are flexible and can secure themselves really well to uneven or curved surfaces. This is very different from molluscs like limpets. With their single shell, they have to be on a very flat surface to be secure, and therefore safe from predators.

In most species of chiton, you can see the eight plates. The exception is the giant in the group – the Gumboot Chiton aka the Giant Pacific Chiton. In this species, the girdle fully covers the plates.

See the photo below and my blog dedicated to Gumboot Chitons at this link. That blog includes photos of their “butterfly shells” and video of Gumboot Chitons spawning. Yes, you can then discern males from females!

Gumboot Chitons are another species in these rich waters that are the “biggest of their kind in the world”. The maximum size of Cryptochiton stelleri is reported to be 35 cm!

Nature once presented me with the following opportunity to take a picture that shows the diversity of molluscs. I did not move the species into the positions you see in my photo below.

1. Keyhole Limpet, protected by its single-shelled cap and by sucking down on flat surfaces. This individual is in a precarious position for predation because it is not secured to a flat surface.

2. Wrinkled Amphissa Snail, protected by its single shell and a keratinous “trapdoor” (operculum) that seals the shell.

3. Pomegranate Aeolid (nudibranch species), with no shell but protected by the stinging cells obtained from its prey – the Raspberry Hydroid.

4. Blue-Line Chiton protected by its eight shell plates and a strong band of muscle that lets it solidly adhere to non-flat surfaces.

Sources:

- Berkley Education – The Polyplacophora, Chitons, the eight-shelled molluscs

- Science Direct – Polyplacophora

- Shape of Life – Chiton

- Sigwart JD. Morphological cladistic analysis as a model for character evaluation in primitive living Chitons. Am. Malacol. Bull. . 2009;27:95–104

- Tradtional Animal Foods of Indigenous Peoples of Northern North America – Chitons