Underwater Smoking Log and the Worm That is Not a Worm?

Submerging into the dark, you never know what you are going to see.

It is a large part of what is so intoxicating about diving in cold, dark waters – all the mystery; all the wonder; all the opportunity for learning and sharing.

So what was it today?

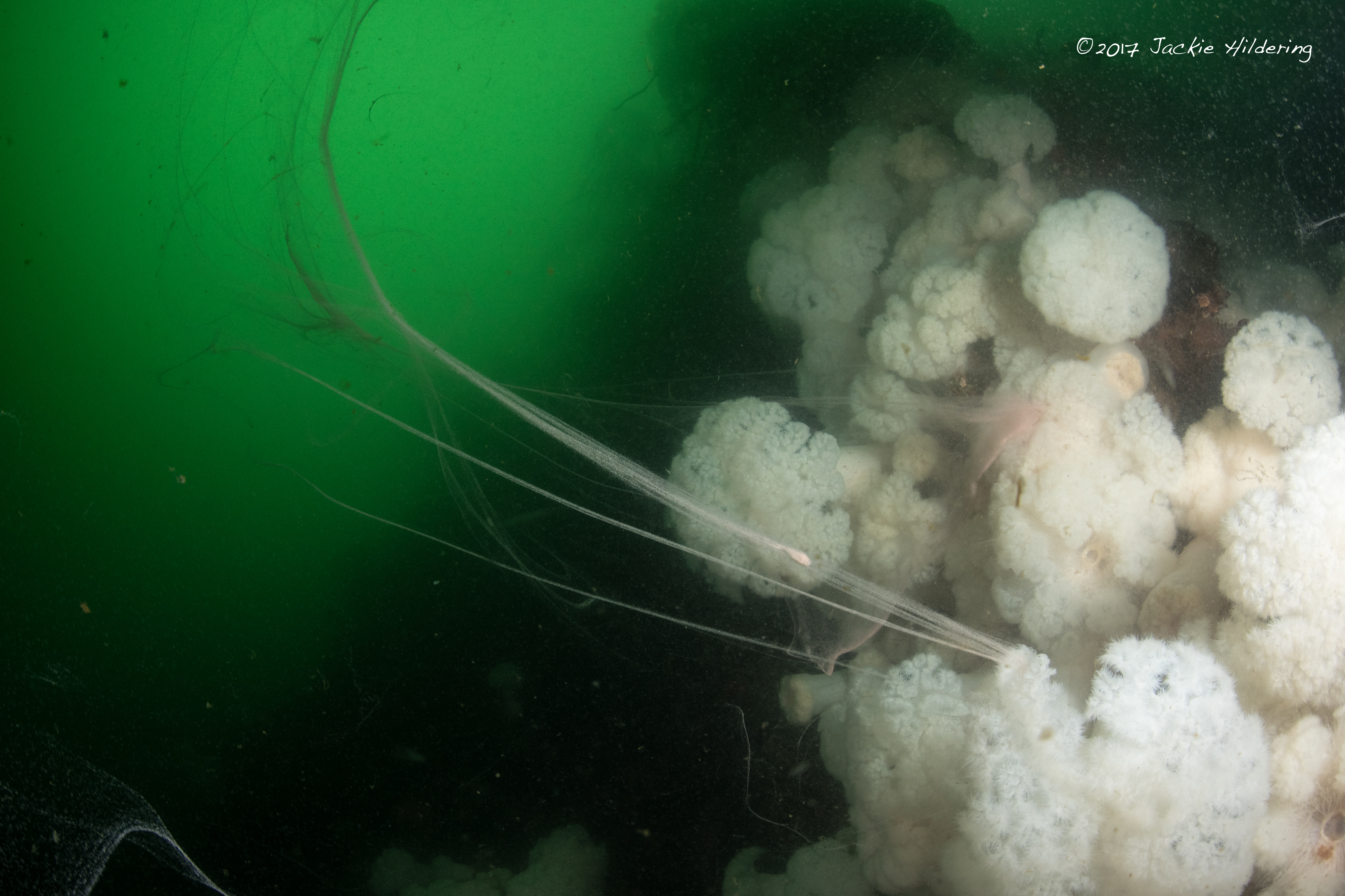

This – a smoking log at about 6 m depth!

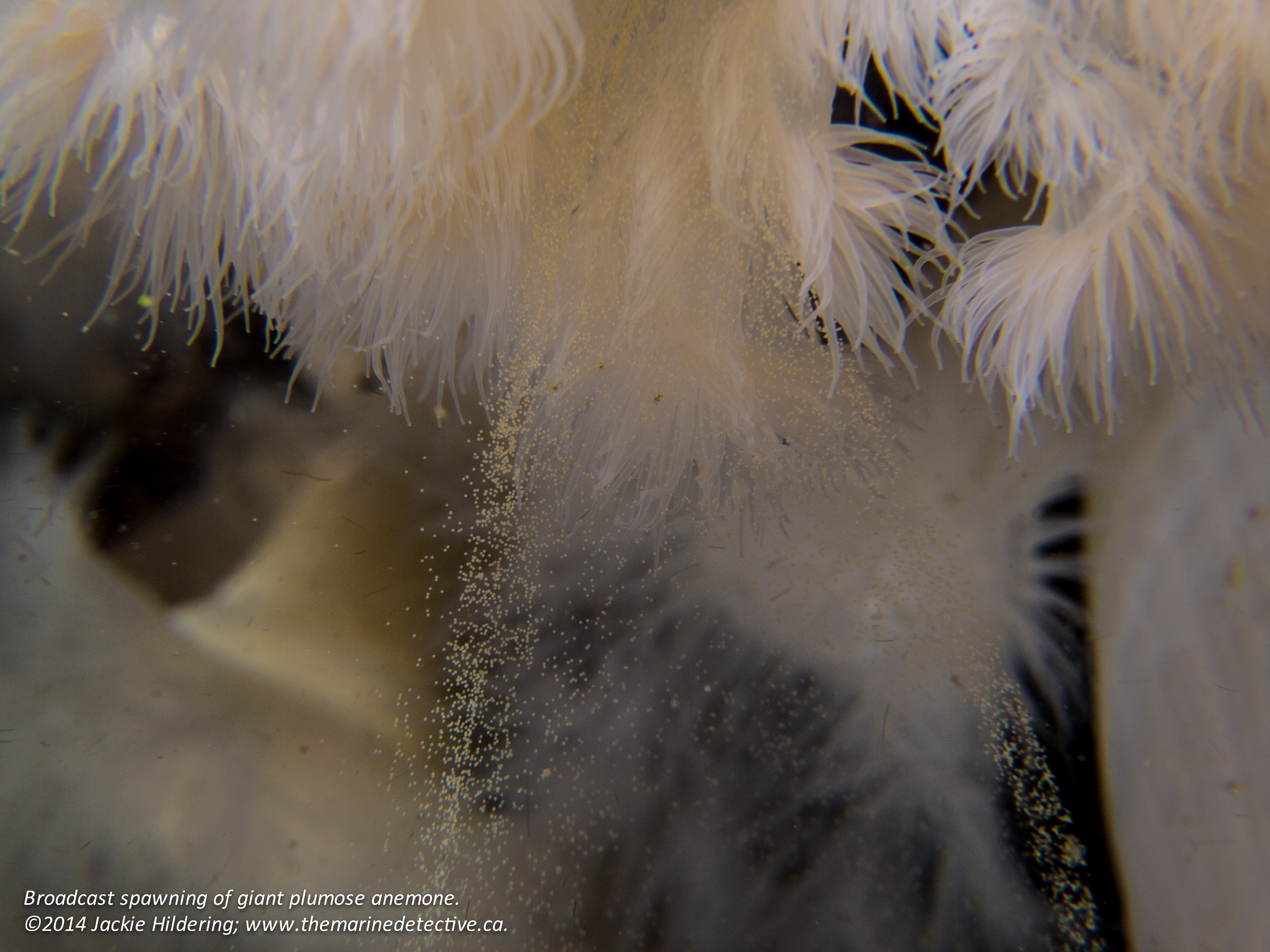

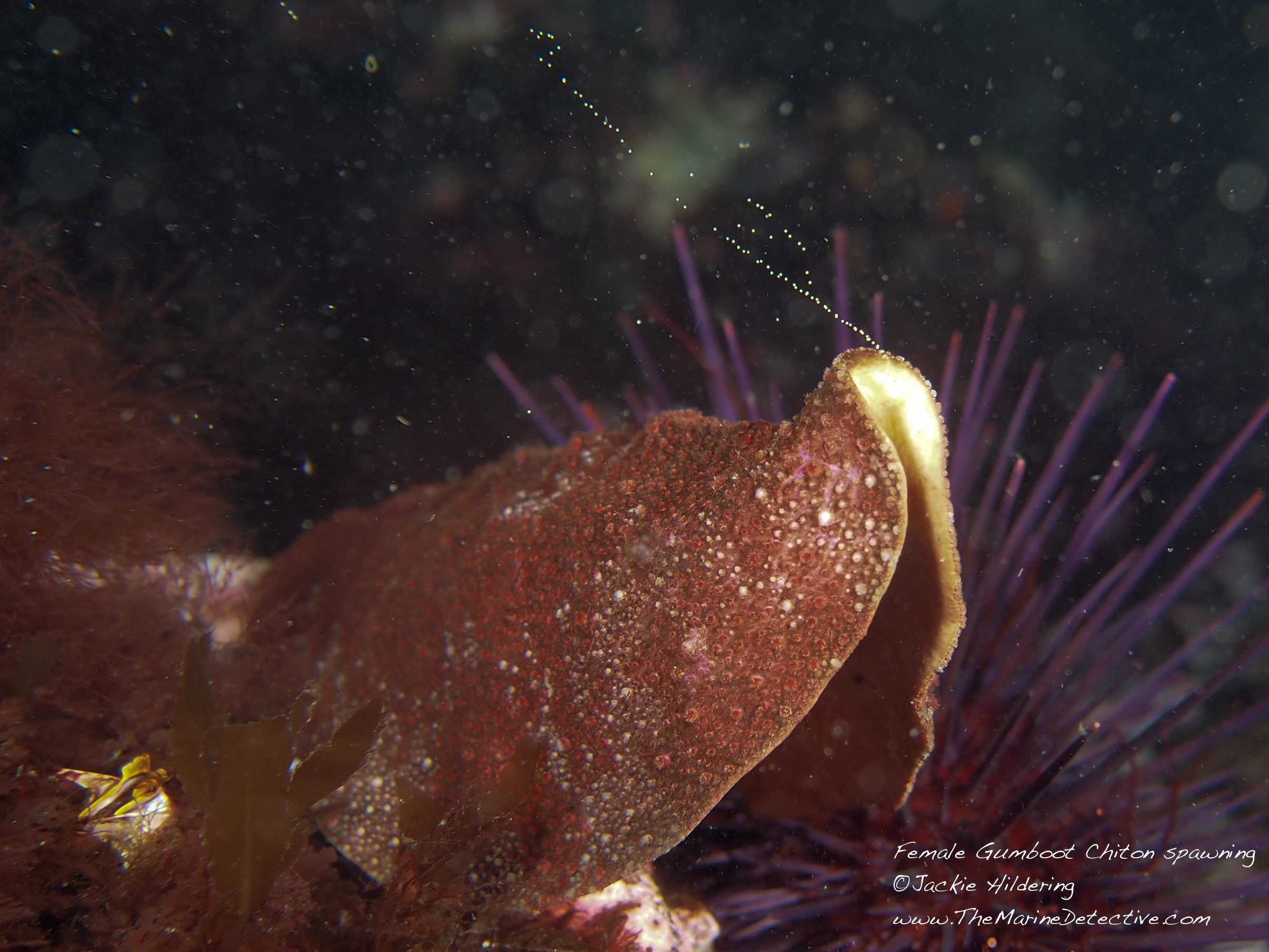

The “smoke” was brief but intense and of course it was not smoke at all. It was the spawn of some animal. Many marine invertebrates are broadcast spawners where all individuals in an area release their sex cells at the same time to enhance the chances of fertilization.

I knew the source of the “smoke” had to be a shipworm species since it was coming from a rotting log with lots of tunnels bored into it. I then had to do a bit of reading to be sure of whether it was the invasive Naval Shipworm (Teredo navalis), or the indigenous Northwest Shipworm (Bankia setacea).

Either way, shipworms are not worms at all!

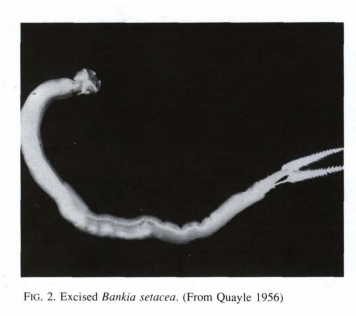

Shipworms are saltwater clams. They look like a worm in a calcareous tube but have two small shells at the front of their bodies that are specialized to bore through wood, much to our dismay! The clams also have symbiotic bacteria that release an enzyme to help break down the cellulose in the wood.

I believe in this case it was the Northwest Shipworm that was spawning and the initial cue for the synchronous release of sex cells in this species is believed to be a sudden change in temperature or salinity. Once the spawn begins, it is believed that neighbouring Northwest Shipworms drawing water into their siphons detect the spawn and that this further triggers them to release their sex cells.

The Northwest Shipworm it is more common in BC than the Naval Shipworm; the tunnels in the wood looked like those caused by this species; but also relevant in my knowing it was this species is that I saw eggs being released as well as sperm.

With the oh-so-successful Naval Shipworm that originated in the Atlantic but is now boring through wood in all the world’s oceans, only the males release sex cells. Sperm are then drawn into females’ inhalant siphons; the eggs are fertilized and develop in the female’s gills in huge numbers to be released as free-swimming larvae.

Northwest Shipworms spawning. The white material on the logs is known as “frass”- waste discharged through the clams’ excurrent siphons. March 8, 2015 ©Jackie Hildering.

The Northwest Shipworm does not have this reproductive strategy. With both genders broadcast spawning, you can imagine how many sex cells need to be released for successful reproduction.

After about 3 weeks (at 12 – 15°C), the Northwest Shipworm larvae appear to be able to detect wood. They attach themselves, soften the wood, bore into it, develop into adults and cause economic discontent in we humans. This is especially the case in the logging industry which depends on transporting and storing wood in the Ocean.

Apparently the Northwest Shipworm can burrow 10 cm per month at temperatures greater than 10°C. See here for examples of the damage to wood by this species. If you are a Northern Vancouver Islander, you can see how this wood has been used as a decorative wall covering in the Whale Interpretive Centre.

For me, there was no discontent today. It was a wonder to be swimming by at the exact time this species was spawning. Providing me with a further opportunity to . . . smoke out facts about our marine life and share them with you!

Related blog post:

Sources:

- http://www.asnailsodyssey.com/LEARNABOUT/CLAM/clamHabi.php

- http://www.asnailsodyssey.com/LEARNABOUT/CLAM/clamComp.php

- http://www.asnailsodyssey.com/LEARNABOUT/CLAM/clamRepr.php

- http://web.forestry.ubc.ca/fetch21/FRST308/lab8/bankia_setacea/shipworm.html

- http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/Library/138806.pdf