Very Rare Fish Find: King-of-the-Salmon (Trachipterus altivelis)

Last updated 2026-01-09

The original post below was about a sighting of this species in Port McNeill in 2012. The blog has since been updated with additional sightings and details (including video about the species astounding feeding adaptations).

See below for the extraordinary feeding method of the King-of-the-Salmon by which they extend their jaw. This member of the ribbonfish family belongs off our coast. To date I have not been able to verify if the origin of the name of the species is indeed from Makah legend.

Here’s a finding to enhance your sense of wonder about the sea and how little we know about its inhabitants.

On March 23rd, 2012 Darren and Joanne Rowsell found this dead specimen on the beach at Lady Ellen Point, Port McNeill, British Columbia, Canada. When the photos landed in my inbox, I almost fell off my chair recognizing how rare a find this was. It’s a King-of-the-Salmon (Trachipterus altivelis). The adults feed in the open ocean at depths of 900+ m (3,000 feet) so they hardly ever wash ashore and I had never seen one before.

The King-of-the-Salmon belongs to the ribbonfish family (Trachipteridae). You’ll note from Joanne’s photos that the species is indeed very ribbon-like. It is extremely thin and maximum confirmed length is 2.45m (Savinykh and Baitalyuk. 2011). The long, high, crimson coloured dorsal fin is also very reminiscent of a ribbon, tapering down the full length of the fish’s back. These fish move in a snake-like fashion, undulating their long bodies.

The unique common name of the King-of-the-Salmon is said to originate from Makah First Nation legend. The legend is said to be that the fish was believed to be the “king” that would lead salmon back to their rivers to spawn and that to kill one was believed to bring bad luck, causing the death of the salmon. The Makah, like other fisherfolk, must occasionally have caught one on their lines or in their nets. HOWEVER, I have never been able to verify if this is indeed a Makah legend.

Photo Joanne Rowsell.

Video ©Josh Billauer showing the dorsal fin of a King-of-the-Salmon – November 2025 near San Diego.

Range:

The species’ range is believed to be from the Gulf of Alaska to Chile.

Diet and Feeding Method:

Smaller King-of-the-Salmon do feed closer to shore and their diet is known to include copepods, annelid worms, fish scales, and fish larvae. Larger individuals feed on copepods, krill (euphausids), polychaetes (bristle worms, small pelagic fish, young rockfish, squid, and octopus. Part of what makes the species so unique is that they can capture (and process prey) by extreme protrusion of the upper jaw. See photos below.

From Ferry, et al (notably the ONLY research I could find on this species): “T. altivelis does appear to have earned the title of “most extreme”in terms of premaxillary protrusion. The distance to which the upper jaw is protruded anteriorly away from the head exceeds that of any other known species . . .the gut was examined in an attempt to gain further insight into this species’ecology. The gut was empty, but the anatomy was unusual and potentially suggestive of extreme foraging habits. There were hundreds of very small diverticuli lining the gut, which suggest to us a mechanism for increasing digestive surface area and/or efficacy. This species has been described as a deep-midwater forager on crustacean zooplankton (Hart, 1973; Shenker, 1983), which is consistent with such mechanisms.”

Video ©Josh Billauer showing how the King-of-the-Salmon can protrude its jaw – November 2025 near San Diego.

Predation:

I presume that stomach content studies have allowed science to determine that the predators of the King-of-the-Salmon include the Bigeye Thresher Shark (Alopias superciloosus), and the Longnose Lancetfish (Alepisaurus ferox).

Swimming:

From Dr. Gavin Hanke of the Royal BC Museum: “King-of-the-Salmon swim by passing a sine wave down their dorsal fin – they can get a fair bit of speed just by doing that. They can also reverse using the same fin flutter. They slowly turn by putting a curve in the body. However, in the first few seconds of the linked video you can see that they also swim in a more typical fishy way (using eel-like body oscillation) when they need a burst of speed or a really quick turn.” See video below of one swimming.

And THAT appears to be all that is known about the King-of-the-Salmon – yet another one of our remarkable marine neighbours.

From Ferry, et al (2019): ” While much work remains regarding the ecology of T. altivelisa nd its relatives, it is certain that this fish holds many surprises yet in store”. No doubt!

Sources:

- Alaska Fisheries Science Centre; Ichthyoplankton Information System

- CBC News; September 24, 2017; ‘Very rare’ King-of-the-Salmon fish found on Vancouver Island beach

- Ferry, L.A., Paig-Tran, E.W., Summers, A.P., & Liem, K.F. (2019). Extreme premaxillary protrusion in the king-of-the-salmon, Trachipterus altivelis. Journal of morphology.

- Fishbase

- Fishwise Universal Fish Catalogue

- iNaturalist – King-of-the-Salmon

- Love, Dr. Milton. Certainly More Than You Want to Know about the Fishes of the Pacific Coast: A Postmodern Experience.

- Martinez CM, McGee MD, Borstein SR & Wainwright PC. 2018. Evolution of Feeding Motions.

- Royal BC Museum; October 11, 2018; “We Three Kings“

- Salem News; July 23, 2006; “Strange Fish Found on Beach Near Seaside”

- Savinykh, V. F. and A. A. Baitalyuk. 2011. Taxonomic status of ribbonfishes of the genus Trachypterus (Trachipteridae) from the northern part of the Pacific Ocean. J. Ichthyol. 51:581–589.

- Wikipedia

Sightings from Washington and BC – photos and video.

NOT a comprehensive account of all sightings!

2021

May 12, 2021: King-of-the-Salmon washed up at Witty’s Lagoon near Mechosin documented by John Michael Thorne.

2020

September 18, 2020: King-of-the-Salmon washed up at Whiffen Spit (Sooke) documented by Dana LeComte (photos below).

July 18, 2020: Live King-of-the-Salmon documented by Gary Bodine at Pillar Point, Washington.

June 24, 2020: ~1.5 m long King-of-the-Salmon found struggling to stay upright by Al Champ and Wendy Cooper in East Sooke (photo below).

June 8, 2020: King-of-the-Salmon documented by Harbor WildWatch in Salt Creek, west of Port Angeles, Washington. They provided the insight that “We speculate that this individual swam too close to shore and was killed by the waves as there was no evidence of predation. These are thin delicate fish adapted to the deep ocean. The tide pushed it up into the creek where it was discovered.”

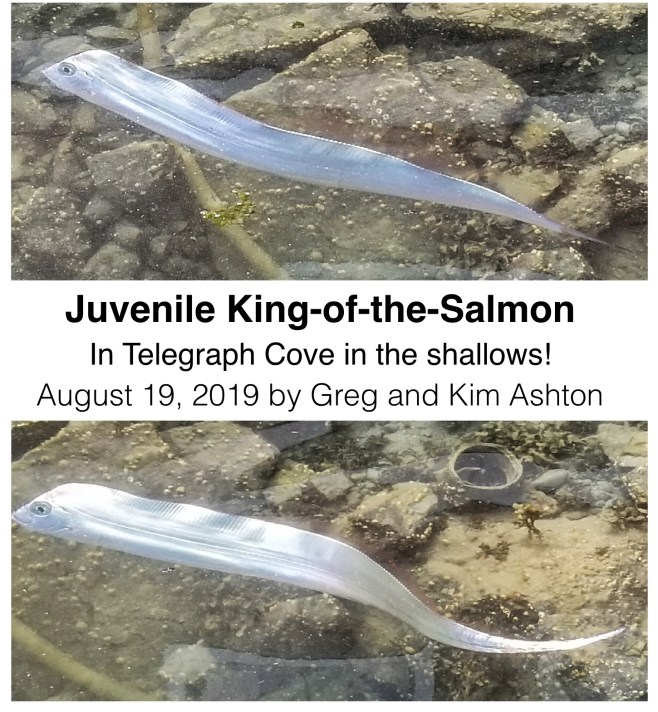

2019

2017

King-of-the-Salmon found near Oak Bay, British Columbia on September 21, 2017 by Ben Clinton Baker. It will end up on display in the Shaw Centre for the Salish Sea in Sidney, British Columbia. Photo: Oak Bay

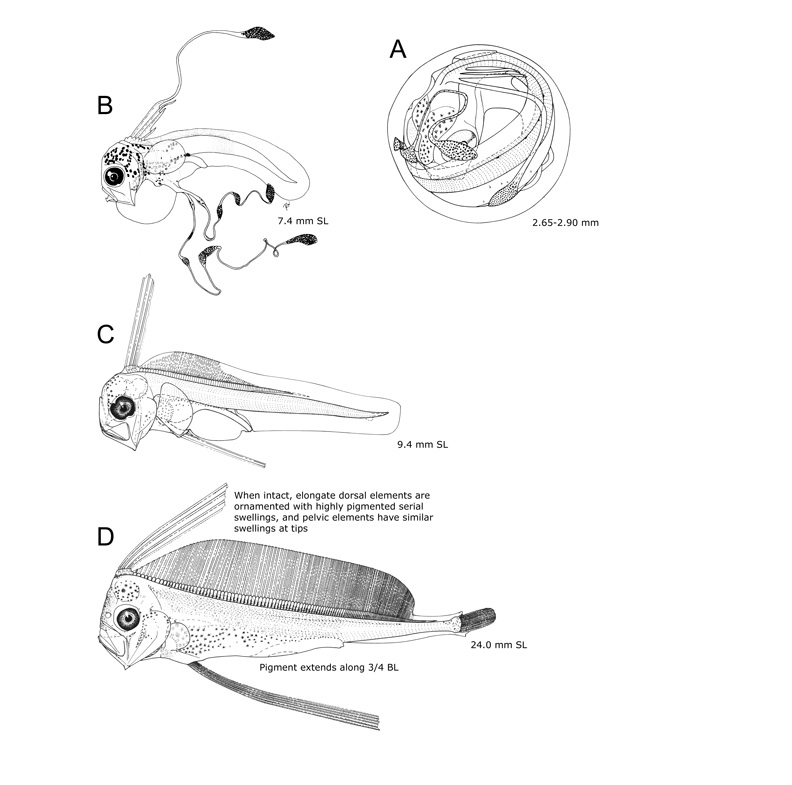

Plankton life stages of the King-of-the-Salmon

Credits:

A: Matarese, A.C., and E.M. Sandknop. 1984. Identification of fish eggs. In H.G. Moser, W.J. Richards, D.M. Cohen, M.P. Fahay, A.W. Kendall, Jr., and S.L Richardson (eds.), Ontogeny and systematics of fishes. Spec. Publ. 1, Am. Soc. Ichthyol. Herpetol., p. 27-31. Allen Press, Lawrence, KS, 760 p.

B: Charter, S.R., and H.G. Moser. 1996.Trachipteridae: Ribbonfishes. In H.G. Moser (ed.), The early stages of fishes in the California Current region. CalCOFI Atlas 33, p. 669-677. Allen Press, Lawrence, KS, 1505 p.

C and D: Matarese, A.C., A.W. Kendall, Jr., D.M. Blood, and B.M. Vinter. 1989.

Laboratory guide to early life history stages of Northeast Pacific fishes. NOAA Tech. Rep. NMFS 80, 652 p.

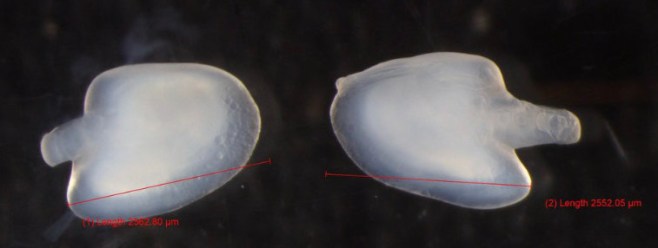

Otoliths / Ear Bones