The rarest of the rare? Haliclystus californiensis in British Columbia?

[Last updated on November 3, 2025.

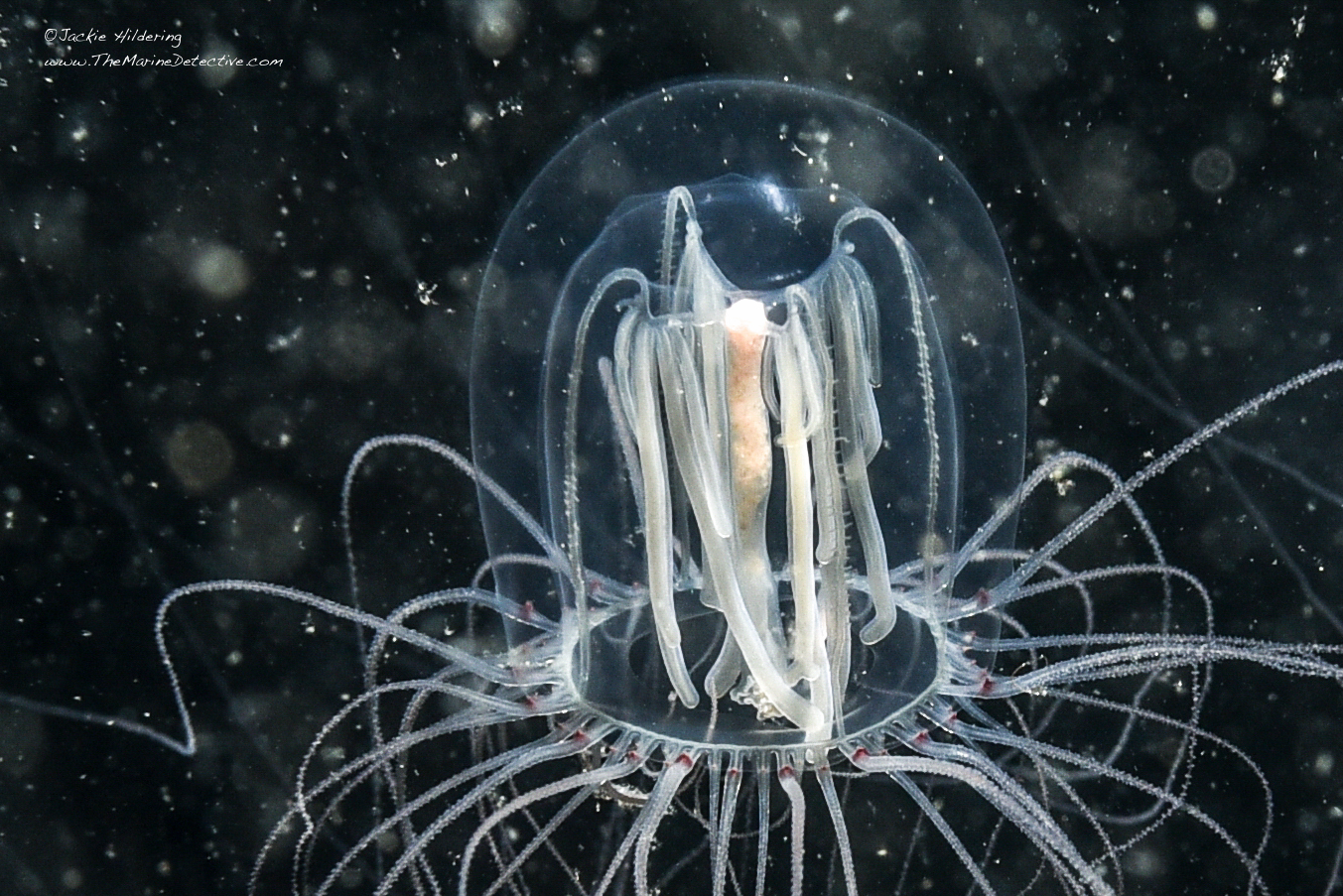

Can a 2 cm stalked jelly make you feel small? Yes.

Can it fill you with awe, wonder, affirmation, purpose, and drive? Yes.

Does it make it feel like all the immersion, the cold, and the learning from this little bit of the planet, somehow makes a positive difference? In a quiet voice, I say . . . yes.

It has been confirmed by Claudia Mills that I have the identification of this stalked jelly correct as Haliclystus californiensis. Note that:

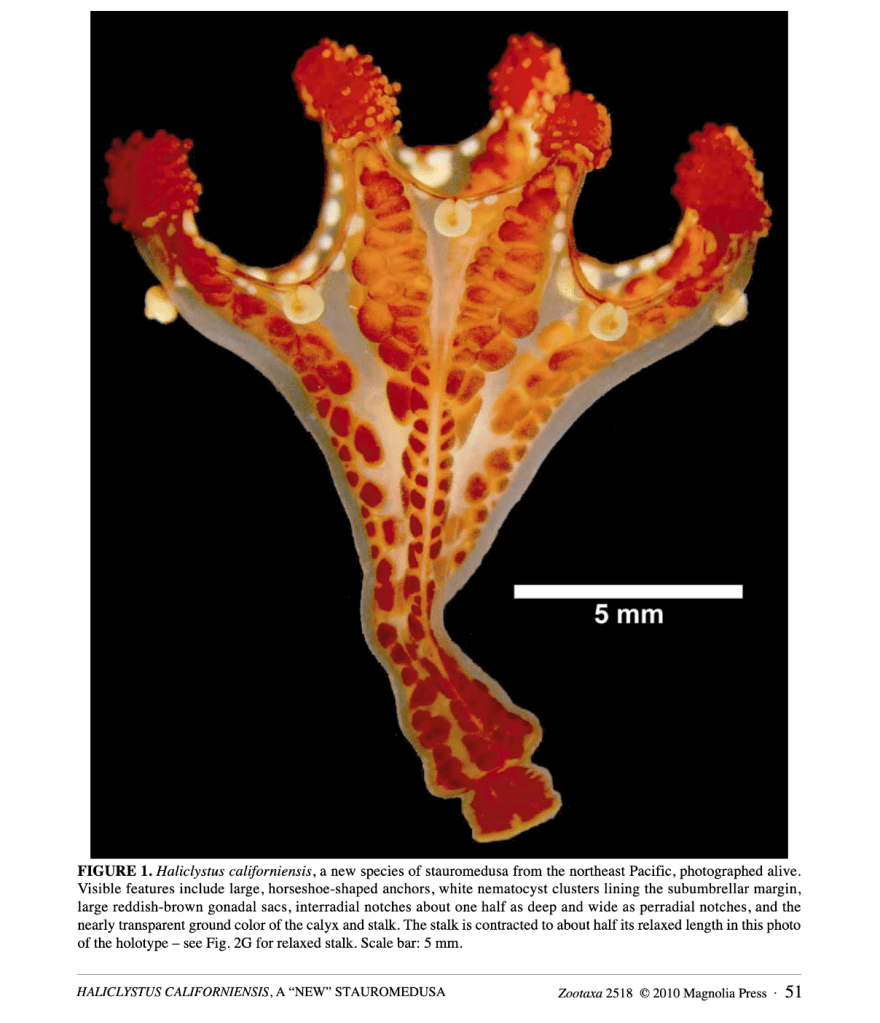

- It has only been recognized as a distinct species in 2010 (Kahn et al., 2010). At the time of that publication, only 10 individuals had been found and only “from southern to northern California in coastal waters” (hence the species name “californiensis“).

- There are only two other known sightings in British Columbia. One in 2017 as a result of a collaboration including the Smithsonian Institution’s Marine Global Earth Observatory and the Hakai Institute. Additionally, I learned from Claudia Mills that one was sighted near Bamfield by Ron Larson in October 1983.

- This would be only the 25th global documentation to be included on the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, which, since the research of Kahn et al. in 2010, includes findings of the species in Sweden and Denmark. Note that there is doubt about whether the individuals documented in the Atlantic are indeed the same species.

Are they deep-dwelling? No. In the research I reference above, it is stated that they are known from depths of 10 to 30 metres. I found this one at about 6 metres depth.

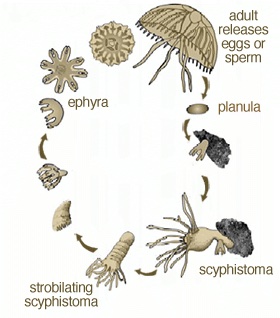

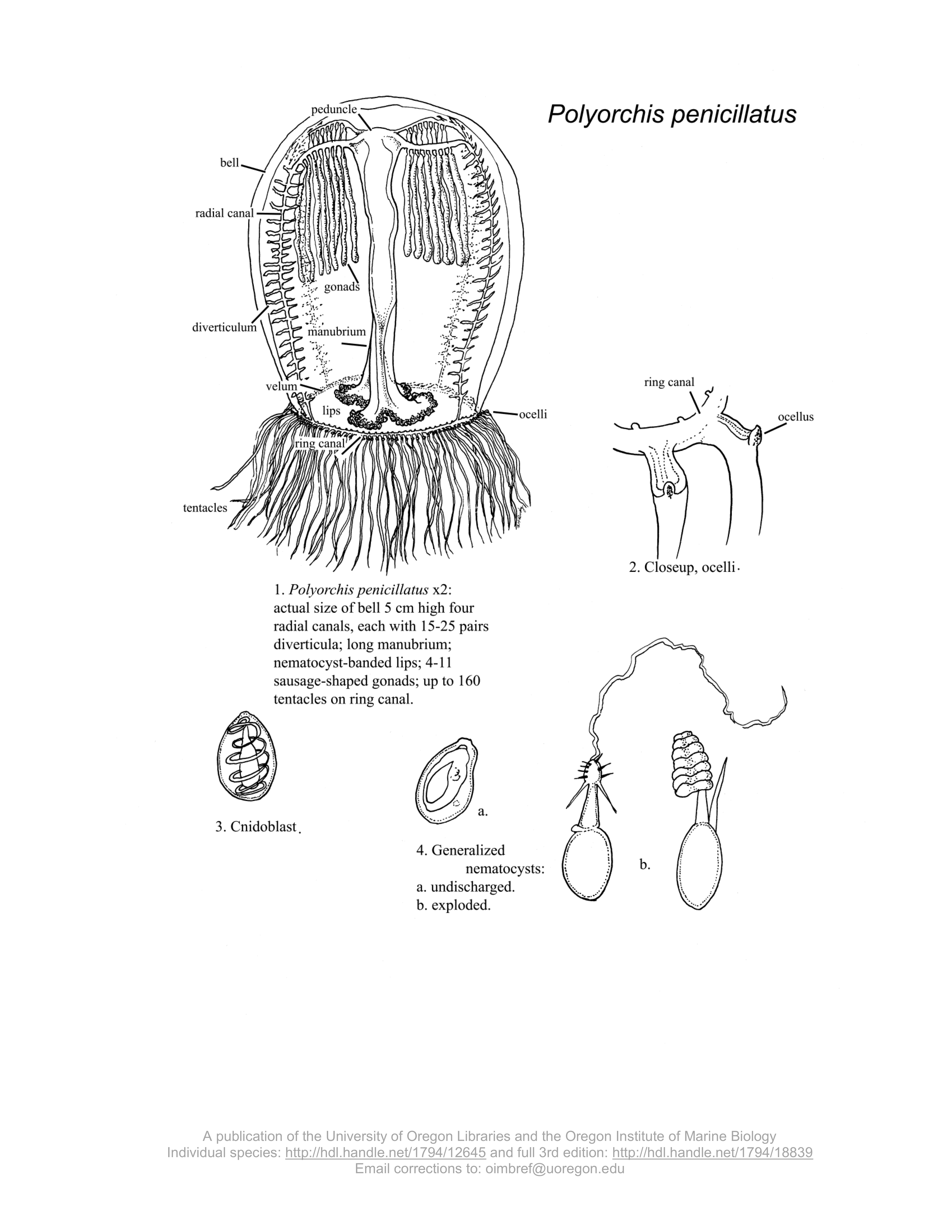

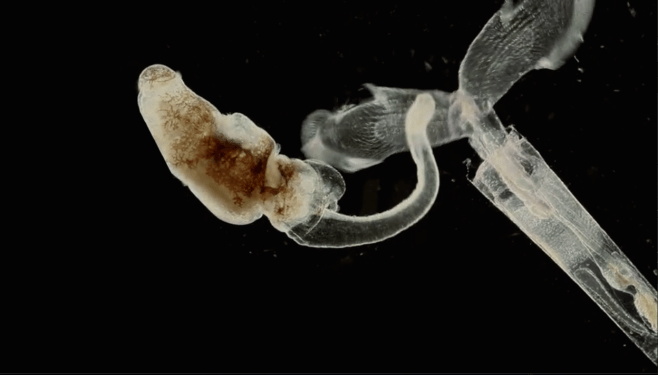

What are stalked jellies? They never become free-swimming, bell-shaped medusae like other jellies. They attach by their sticky stalk and have 8 arms with pom-pom-like clusters of tentacles at the ends. These tentacles have stinging cells to catch small crustaceans, which are then moved to the mouth at the centre of the 8 arms. If detached, stalked jellies can grip a surface with their tentacles and quickly reattach their stalk.

How did I find this one? There was fortuitousness involved. But also, I was looking when many would not. I was looking because of what I have been able to learn previously.

The sighting was on October 30, 2025, when diving with a group I organized to go to God’s Pocket Resort. It was our last dive of the trip and the last dive for the God’s Pocket Team for 2025. It had already been an astounding morning, which included documenting Humpbacks and Bigg’s Killer Whales while on the boat. Captain Bryan had been considering another dive site in Browning Pass, but the current and the potential for him to get more opportunistic whale IDs (with telephoto lens) while we were diving, led him to choose this location.

We had dived this site earlier in the week, and then too I had rushed to the “end” where I know there is a little patch of Eelgrass. I was looking for another species of Haliclystus I have found there before, for which a species name has NOT been assigned. This does not mean in any way that I discovered it, but rather that researchers have not yet published the research describing how it is morphologically and genetically distinct. See photo below.

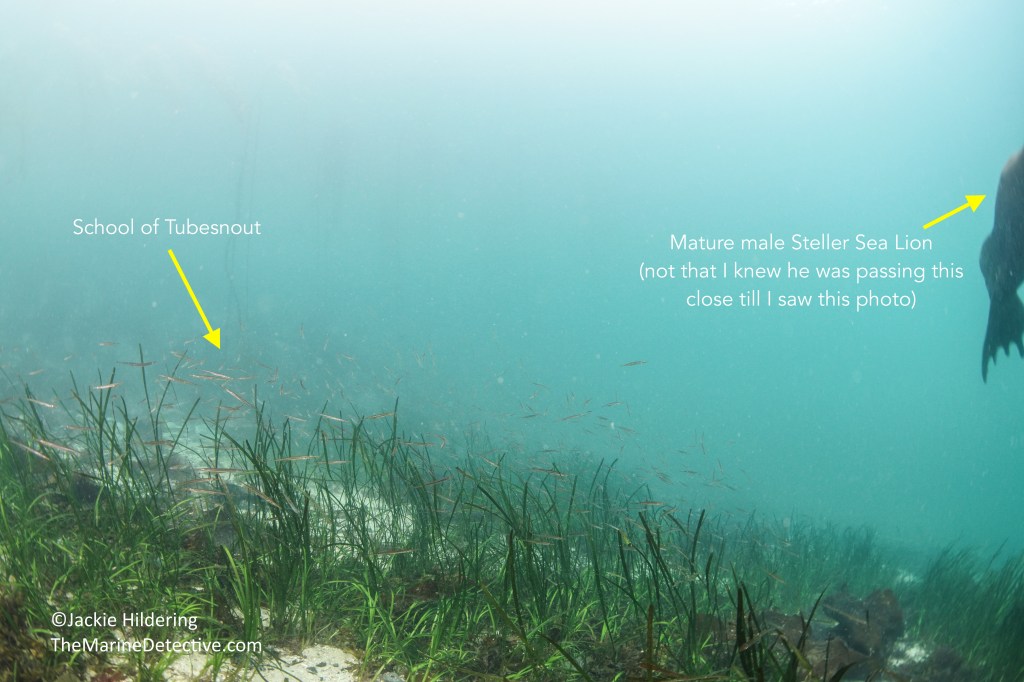

I reached the Eelgrass bed and watched a school of Tubesnout (fish) swim around. Then, I focused on the Eelgrass to see if, maybe this time, I could find the undescribed species. Later, my photos would reveal just how intent I had been. See below for a photo of the school of fish with the flipper of a mature Steller Sea Lion in the frame. I had noticed he had passed so close to me. Yes, I can find 2 cm stalked jellies, and miss a ~3 m, 1,000 kg Steller Sea Lion.

And then, there it was. My brain started screaming immediately, knowing this was a unique species. Does it matter? It does to me. And maybe, it does to you.

May this add to wonder, appreciation, and the appropriate humility that we humans know so little about even the marine species that live in the shallows. May that foster care, and actions that benefit all of us connected by water and air on this ocean planet.

Sources:

- Global Biodiversity Information Facility Backbone Taxonomy – Haliclystus californiensis

- iNaturalist – Haliclystus californiensis

- KAHN AS, MATSUMOTO GI, HIRANO YM, COLLINS AG. Haliclystus californiensis, a “new” species of stauromedusa (Cnidaria: Staurozoa) from the northeast Pacific, with a key to the species of Haliclystus. Zootaxa. 2010;2518(1). doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2518.1.3

- Mills, Claudia (pers comms 2025-11-03) about known past documentations of this species:

- Southernmost is Santa Cruz Island (1950, Gwilliam).

- Four in central California noted by Kahn (2010).

- One in Depoe Bay, Oregon.

- One near Calvert Island on the Central Coast of British Columbia on August 1st, 2017 as a result of a collaboration including the Smithsonian Institution’s Marine Global Earth Observatory and the Hakai Institute.

- One near Bamfield, southwest Vancouver Island, British Columbia, by Ron Larson, October 1983.