What’s the Bigg’s Deal?!

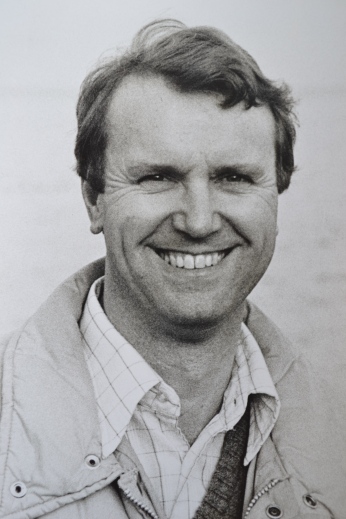

Super hero – Dr. Michael Bigg. Achieved so much before passing at just age 51 (1939 to 1990). Photo ©Graeme Ellis.

Updated March 27, 2024. New research paper putting forward the case for Bigg’s and Resident Orca to be recognized as distinct species. See here.

Morin Phillip A., McCarthy Morgan L., Fung Charissa W., Durban John W., Parsons Kim M., Perrin William F., Taylor Barbara L., Jefferson Thomas A. and Archer Frederick I. 2024 Revised taxonomy of eastern North Pacific killer whales (Orcinus orca): Bigg’s and resident ecotypes deserve species status R. Soc. Open Sci.11231368231368

_____________________

Original post:

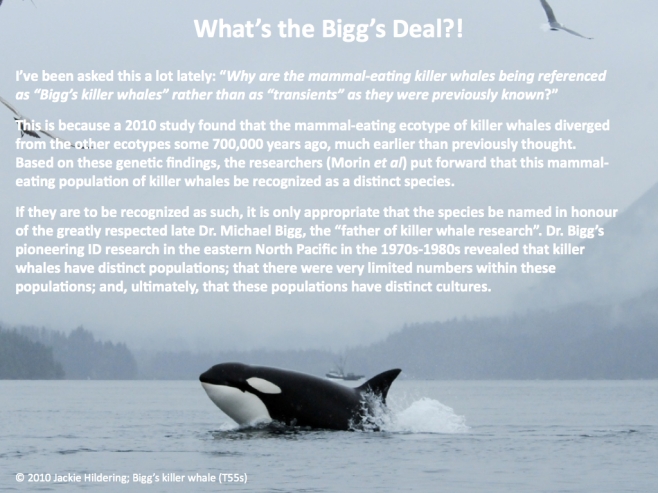

What’s the Bigg’s Deal? I’ve been asked this a lot lately: “Why are the mammal-hunting killer whales being referenced as “Bigg’s Killer Whales” rather than as “Transients” as they were previously known?”

This is because a 2010 study found that the mammal-hunting ecotype of Killer Whales / Orca diverged from the other ecotypes some 700,000 years ago and the researchers (Morin et al) put forward that they be recognized as a distinct species.

If they are to be recognized as such, many in whale-research-world believe it is only appropriate that the species be named in honour of the late and great Dr. Michael Bigg whose pioneering Killer Whale ID research in the eastern North Pacific in the 1970s – 1980s revealed that Killer Whales have distinct populations and that there are very limited numbers within these populations.

Ultimately, his research led to the understanding that Killer Whale populations have distinct cultures.

This knowledge of course had huge conservation implications. It was previously believed that there were abundant Killer Whales in the eastern North Pacific and that they all eat salmon in addition to marine mammals; rather than the reality that there are four at risk populations that are genetically and ecologically distinct:

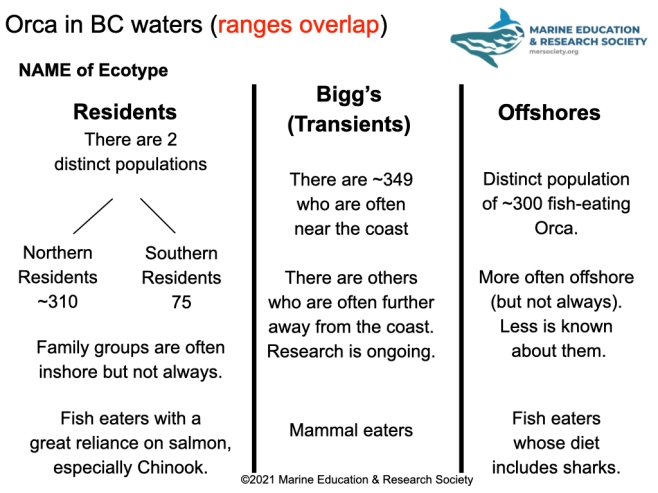

- 1. Bigg’s Killer Whales are marine mammal-hunters (they also eat an occasional bird and, very rarely, a terrestrial mammal). Because they are hunting marine mammals, they generally have to be stealthy and unpredictable (when hungry). The population estimate for this threatened population is ~349 individuals (end of 2018) that are more often along coastal BC, with research ongoing regarding population numbers further off the coast (estimated to be at least 217 whales in 2011; see “Biggs/Transients” information at this link). Their behaviour has changed in recent years, as reported by colleague researchers at the Marine Education and Research Society. They are not so “transient” anymore. In some areas they are more commonly sighted than “Residents” and appear to be travelling, socializing and hunting in bigger groups. They also appear to be more vocal, especially after a kill. This is believed to be due to changes in the location and density of their prey. More seals and sea lions means that they do not have to be as stealthy (65% of the diet of Bigg’s who feed along BC’s coast is seals and sea lions). Status report and further information at this link. Note that there are no documented incidents of Bigg’s Killer Whales in the wild ever injuring a human.

- “Residents” are inshore fish-eating Killer Whales (ingesting an occasional squid too) and there are two distinct populations. The vast majority of their fish diet is salmon and of the salmon species, their absolute favourite is Chinook. (Their diet is also known to include lingcod, halibut, herring, squid, rockfish, flounder). Because salmon is so predictable (salmon return to the river of their birth to spawn and die) and because fish have very bad hearing, these populations of Killer Whales can afford to be highly vocal and use echolocation a lot.

- 2. The Northern “Residents” are a threatened population of some ~302 whales (2018) more often found in northern British Columbia but also in southeastern Alaska and Washington State. Status report and further information here. For the story of one N. Resident Killer Whale family (the A23s) and what their story reveals about us, click here.

- 3. The Southern “Residents” are most often swimming around southern British Columbia and Washington State but are sometimes also in the waters of northern British Columbia, Oregon and California. At only 72 individuals (2019), this population is recognized as being endangered. Status report and further information here.

- 4. Offshore Killer Whales are fish-eaters often found along the continental shelf from the Aleutian Islands to California. To date, published research has confirmed that their diet includes Pacific Sleeper Sharks and Pacific Halibut. The population estimate is 300 individuals (2013) and this too is a threatened population. Status report and further information here.

Summary I made for our Marine Education and Naturalist Society Marine Naturalist Course (2021).

Through the research of Dr. Bigg, the Killer Whales of British Columbia have been studied as individuals longer than any other marine mammal species on the planet – and not only marine species have benefited from this. We all have.

Due to his work, whereby the age, gender, diet and range is known for almost every Killer Whale in British Columbia, these whales “tell the story” of global chemical pollution. The work of Dr. Peter Ross examines the toxins in the blubber and indeed the Killer Whales of BC are the “canaries in the coal mine” informing the science that should shape international policies and regulations regarding toxins.

However, there is also much that has NOT changed since the days of Dr. Bigg’s pioneering Killer Whale research.

At that time, Killer Whales were the scapegoat for declining salmon populations and the “gold rush” on their being put into captivity was likely perceived as a favourable management tool. Conservation costs money, not only for science and management, but also by limiting industries whose activities may negatively impact species at risk.

Flash forward some 40 years to 2013. Dr. Peter Ross’ work with Fisheries and Oceans Canada has been terminated as part of what can only be called the demise of Canada’s ocean contaminants research program and prior to his termination he, like so many other government scientists in Canada, has been constrained in being able to communicate about his research. (Update 2014: Dr. Ross now heads the Ocean Pollution Research Program at the Vancouver Aquarium).

The ultimate Bigg’s Deal is that one person can make a profound positive difference – replacing knowledge where fear and misunderstanding once dwelled.

However, to work against government forces that imperil our environment and suppress science in favour of short-term economic gain, it is going to take a very great many of us to make our voices and actions . . . Bigg-er.

_________________________________________________________

- Towers, Jared & J. Sutton, Gary & J.H. Shaw, Tasli & Malleson, Mark & Matkin, Dena & Gisborne, Brian & Forde, John & M. Ellis, Graeme & Ford, John & Doniol-Valcroze, Thomas. (2019). Photo-identification Catalogue, Population Status, and Distribution of Bigg’s Killer Whales known from Coastal Waters of British Columbia, Canada

- Bigg’s Killer Whales, see this link and click “Bigg’s (Transients)

- British Columbia Magazine; November 2016; BC’s Pioneer of Killer Whale Research.

- Blog item by fellow Marine Education and Research Society researchers on changes in how Transients behave; February 6, 2014; “Transient killer whales not so transient anymore much to dolphins’ dismay”

- Global News; February 5, 2014; “Epic ocean battle: Orca vs dolphin” [Video, with interpretation by DFO’s James Pilkington, of Bigg’s Killer Whales attacking Pacific White-Sided Dolphins outside Nanaimo on February 3rd, 2014.]

- CBC News, July 26, 2019; Shark-eating offshore killer whales are the ‘mystery animals’ of B.C. waters

- CBC News; January 10, 2014; The Fifth Estate – “The Silence of the Labs“

- Bundling of news items related to the muzzling of Canadian scientists.

- BC Cetacean Sightings Network; December 18, 2012; “What’s in a name?”

- Morin PA, Archer FI, Foote AD, Vilstrup J, Allen EE, Wade P, Durban J, Parsons K, Pitman R, Li L, Bouffard P, Abel Nielsen SC, Rasmussen M, Willerslev E, Gilbert MTP, Harkins T. 2010 Complete mitochondrial genome phylogeographic analysis of killer whales (Orcinus orca) indicates multiple species. Genome Res, doi:10.1101/gr.102954.109

- Morin Phillip A., McCarthy Morgan L., Fung Charissa W., Durban John W., Parsons Kim M., Perrin William F., Taylor Barbara L., Jefferson Thomas A. and Archer Frederick I. 2024 Revised taxonomy of eastern North Pacific killer whales (Orcinus orca): Bigg’s and resident ecotypes deserve species status R. Soc. Open Sci.11231368231368

- Riesch R, Barrett-Lennard LG, Ellis GM, Ford JKB and Deecke VB (2012) Cultural traditions and the evolution of reproductive isolation: ecological speciation in killer whales? Biol J Linn Soc 106(1):1–17, DOI: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2012.01872.x

- Compilation of web-links on Bigg’s Killer Whales