Amber Forest

Sob! I am having a moment.

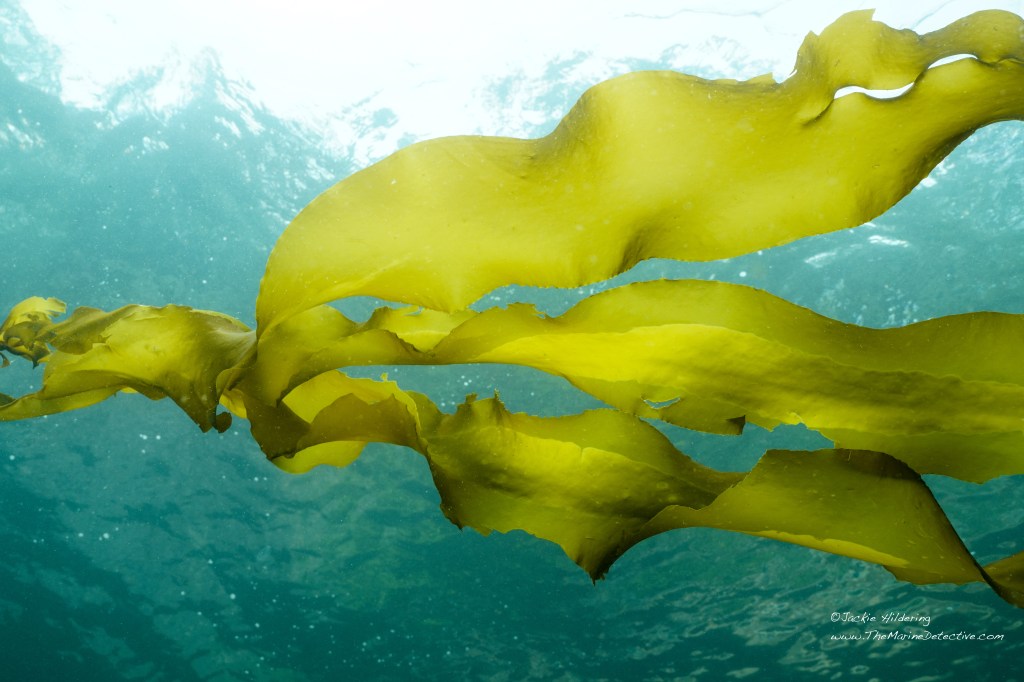

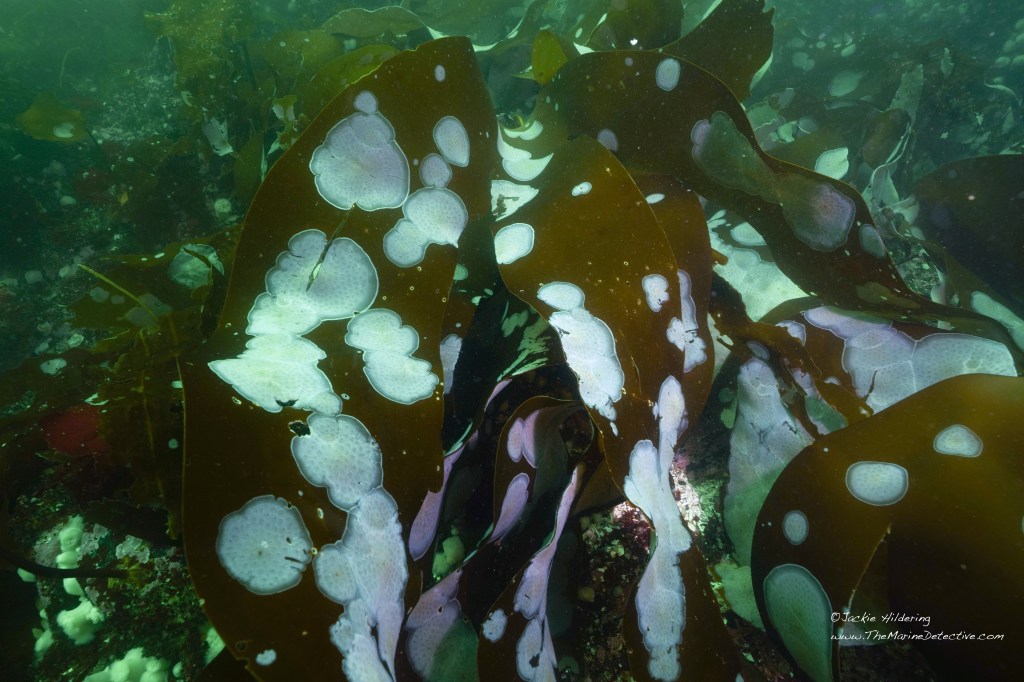

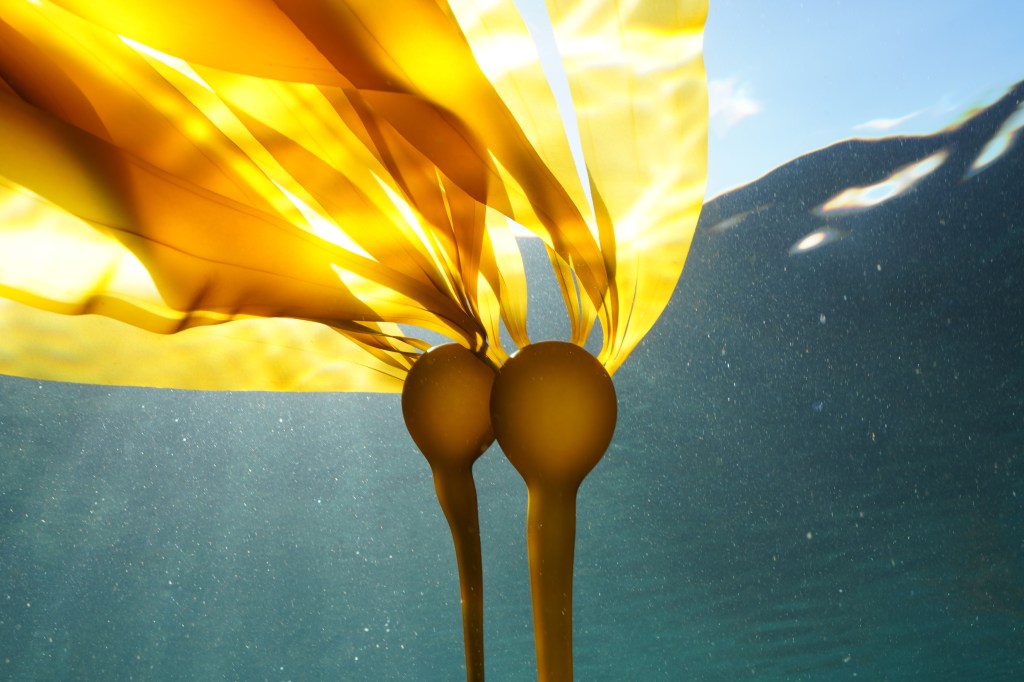

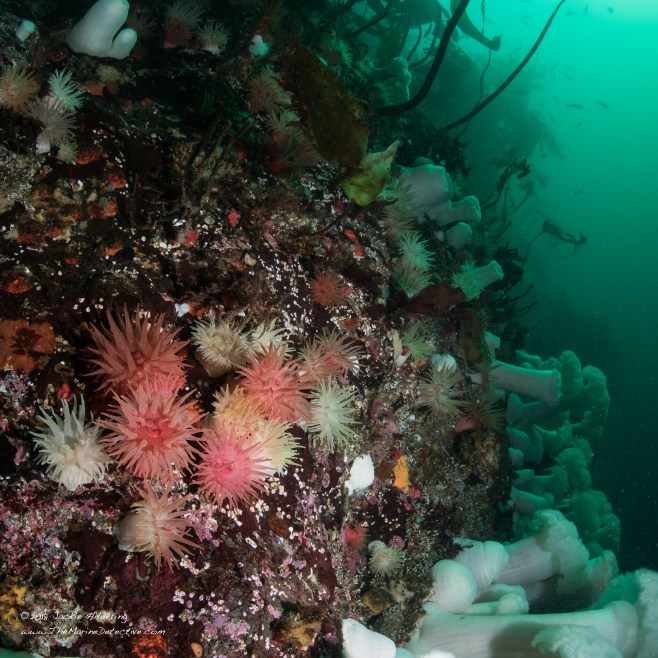

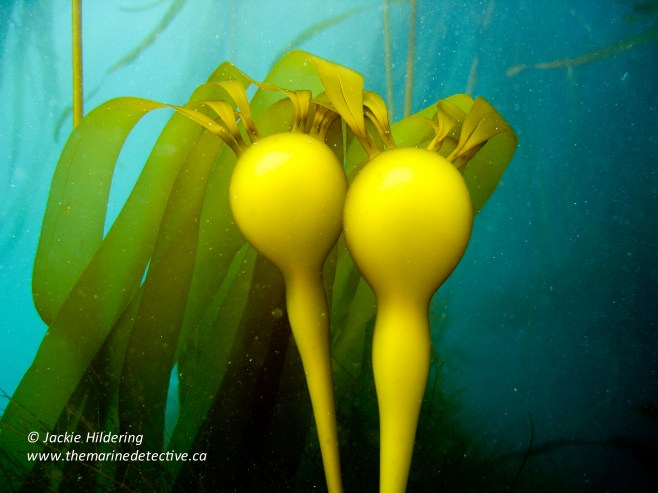

The photos you see here are from the new exhibit “Seaweed: Mysteries of the Amber Forests” at the Shaw Centre for the Salish Sea. Those are my kelp photos. ![]()

I am choking up at typing that. I have never seen my photos printed that big and am massively moved that they are part of this education aimed at increasing awareness and action for algae.

.

. In green – friend and Director of Exhibits & Engagement, Leah Thorpe.

On right, Executive Director of the Centre, Pauline Finn. On left, Director Allan Lane.

Also featured is the art of Josie Iselin. She scans seaweeds with her flatbed scanner and then often places the photos atop historical images from when that species of seaweed was first described.

I am so grateful to Leah Thorpe, Director of Exhibits & Engagement, for all of her work to make this real.

I have NOT seen the exhibit in person but am now strangely compelled to go to 9811 Seaport Pl, Sidney, southern Vancouver Island. How about you? Show me photos when you go?

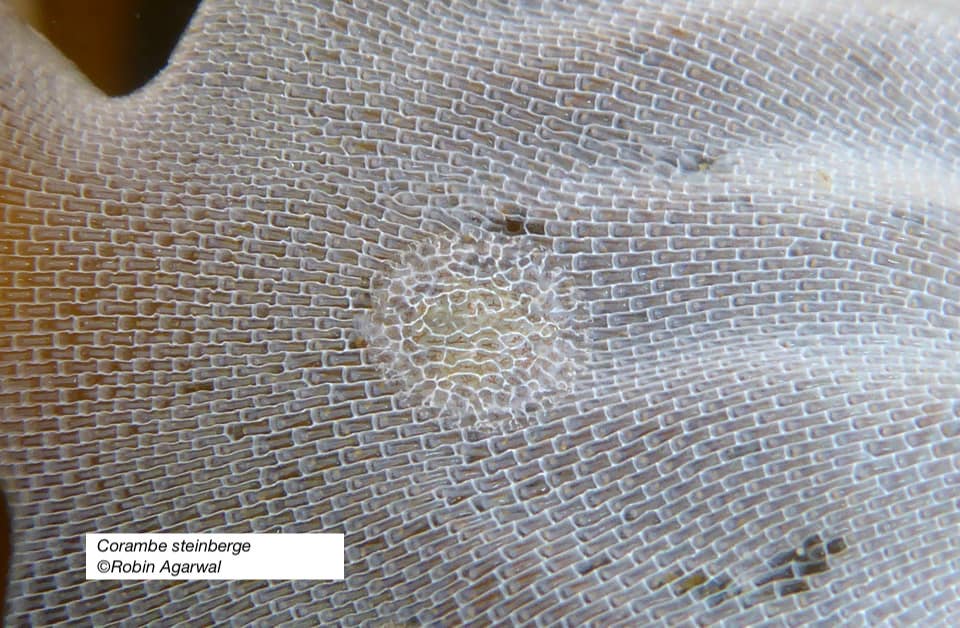

You will be thrilled to see there are also some my Find the Fish challenges in the exhibit but in BIG photos WITH answers. ![]()

How to Help the Kelp, and Why?

The Ocean’s algae, from the microscopic and to the giant kelps:

- Produce at least 50% of the Earth’s oxygen.

- Another result of their photosynthesis is that they absorb very significant amounts of carbon dioxide – a very significant climate-changing gas.

- The algae / seaweeds are producers, converting sunlight to food to fuel the food web. They offer we humans so much nutrition too.

- Kelps are habitat for hundreds of species.

Kelp Is in Trouble

Where every species lives is, of course, because the conditions are right. For example, the temperature is not too cold. It’s not too hot. It’s just right. Yes, this is referenced as the Goldilocks Principle. Changing temperatures are impacting the health of kelp forests, as are other variables involved with climate change such as more frequent and stronger winds ripping away more kelp.

Also, there are far fewer Sunflower Stars due to Sea Star Wasting Disease which is believed to be associated with climate change. Sunflower Stars are predators of Green Urchins. Green Urchins graze on kelp. With less Sunflower Stars, there are more Green Urchins. More urchins leads to more grazing on kelp. In the extreme, this leads to “urchin barrens” where the kelp forest has been grazed away.

Less kelp = less food, oxygen, habitat and buffering of carbon dioxide.

Don’t Despair!

This is not an additional problem. It’s another symptom of the same problem. Whatever you do to reduce fossil fuel use (from consumerism to how you vote), will help the kelp and all that depends on them.

May the knowledge motivate, not lead to fear and paralysis which perpetuates the problem. It truly is the case that if you are not contributing to solutions, you are part of the problem.

Care more. Connect more. Consume less.

The exhibit “Seaweed: Mysteries of the Amber Forests” will be at the Salish Sea Centre for about a year.

See my other blogs about the importance of kelp at this link.