When a Giant Falls . . . and people care.

This photo is of the juvenile male humpback whale that died in the early morning hours of June 12th on a beach in White Rock (some 40 km south of Vancouver).

Fellow Marine Education Research Society (MERS) director, Caitlin Birdsall was on site in her capacity with the British Columbia Cetacean Sightings Network and I have been haunted by her photos ever since she shared them with me.

While the images stir deep despair, they are also achingly beautiful and fill me with a great depth of hope.

People cared enough to place flowers on the deceased little whale.

People cared enough to stand in awe and respect.

People . . . cared.

With this little whale dying on a beach in an urban centre, great public concern and national media attention were attracted, creating a potent opportunity for education.

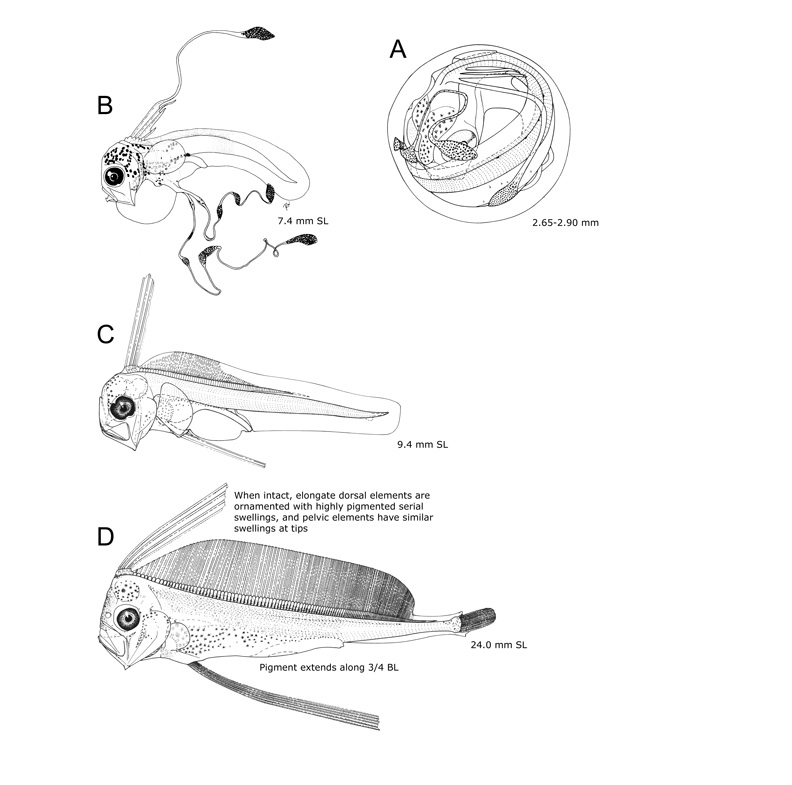

The death of this whale illuminates how little we know about marine life, even the ocean’s giants.

Had anyone seen the whale before? To date, no one has been able to identify this whale as an individual and thereby determine where he might have come from. We at MERS were not able to find this whale in our catalogue nor in that of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

How did the whale die? The whale had an excruciatingly slow death from starvation due to entanglement in fishing gear. The gear had lacerated into the whale’s skin and had cut deep into the whale’s mouth. Ultimately, the young emaciated humpback became stuck on the beach at low tide and died there.

What type of fishing gear killed the whale? Fishing gear that was unfamiliar to local experts. Scott Landry, from the Provincetown Centre for Coastal Studies in Massachusetts, is one of the world’s foremost experts on entanglement and he shared with MERS director Christie McMillan that the line was very likely from offshore longline fisheries and was more difficult to recognize because the hooks had been in the water so long, they had corroded off the lines. Let’s truly absorb that for a moment – the whale may have been entangled so long that he outlasted the hooks on the fishing line.

Do humpback whales get entangled often? Entanglement is identified as a threat in the Recovery Strategy for the North Pacific Humpback Whale in Canada but the threat is very poorly understood. Therefore, we at the Marine Education and Research Society have undertaken an entanglement scar study to determine how often humpback whale entanglement might occur. British Columbia’s vast coastline and relatively new Marine Mammal Response Network unquestionably lead to many undetected and unreported entanglements. Even in the Gulf of Maine where there is a well-established reporting network, studies have determined that less than 10% of large whale entanglements are witnessed or reported and only a fraction of deaths are detected. Scar studies in Southeast Alaska suggest that up to 78% of humpbacks are entangled at some point in their lives.

Are there solutions? Humpback whales of the North Pacific must continue to receive protection under the Species at Risk Act. They are currently listed as “Threatened” but a 2011 assessment suggests they could be down-listed to being of “Special Concern”. This is premature. Not enough is known about the population structure of the North Pacific humpbacks, let alone about threats such as entanglement. With a better understanding of the incidence of entanglement, fisheries regulations could be adapted including gear modifications that allow nets and lines to break-away.

But the lessons here go beyond those relating specifically to humpbacks and to entanglement.

This “case” of an unidentified juvenile humpback dying in on a beach in an urban centre after months of agony, undetected and unreported, testifies to how little we know about our oceans and how easy it is to kill a giant, even with a bit of stray human-made fishing line.

The key to saving whales and the ecosystems for which they are ambassadors, is to retain the humility and connectedness we feel when we see pictures like this, letting it impact our consumer and electoral choices and our value systems. We too often act as if we know it all; that we will be able to “manage” even unknown human impacts; and therefore, we relentlessly assault the oceans in favour of short-term economies.

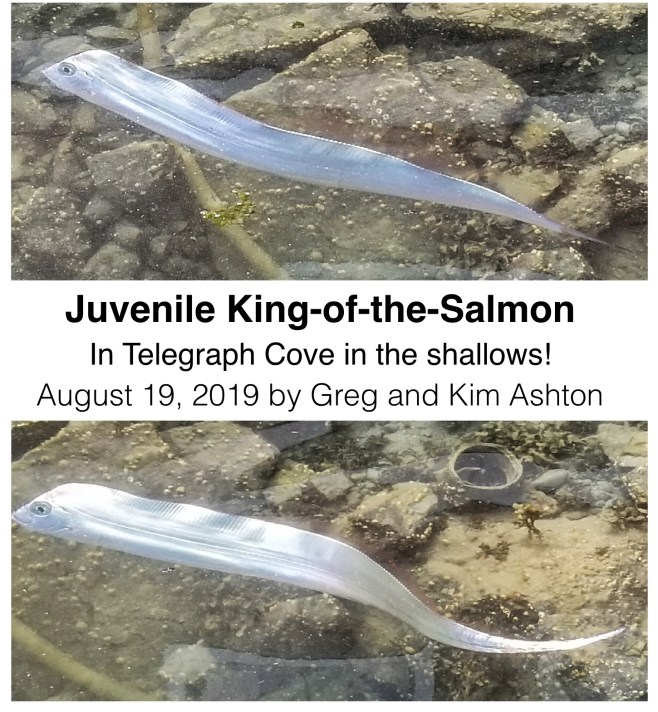

Thanks to the efforts of many volunteers, coordinated by Jim and Mary Borrowman, this little humpback’s skeleton will come to hang in Telegraph Cove’s Whale Interpretive Centre. Maybe the powerful photograph will hang life-size behind it, adding to the potential of this whale’s death leading to some sort of positive gain for the environment and therefore . . . for ourselves.

Sources:

- Neilson, J. L., J. M. Straley, C. M. Gabriele and S. Hills. 2009. Non-lethal entanglement of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in fishing gear in northern Southeast Alaska.Journal of Biogeography 36:452–464.

- Robbins, J. and D.K. Mattila. 2001. Monitoring entanglements of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the Gulf of Maine on the basis of caudal peduncle scarring. Unpublished Report to the 53rd Scientific Committee Meeting of the International Whaling Commission. Hammersmith, London. Document number SC/53/NAH25.

- Robbins, J. and D.K. Mattila. 2004. Estimating humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) entanglement rates on the basis of scar evidence. Report to the National Marine Fisheries Service. Order number 43ENNF030121. 22 pp.

- Robbins, J. 2009 Scar-based inference into Gulf of Maine humpback whale entanglement: 2003-2006, pp. 40: Report to the National Marine Fisheries Service. Order Number EA133F04SE0998.

Strand of the fishing line that led to the death of the whale. © 2012 Caitlin Birdsall. Click to enlarge.

The Vancouver Aquarium’s Dr. Lance Barrett-Lennard takes questions from media. © 2012 Caitlin Birdsall. Click to enlarge.

On February 22nd, I received the following notification: “Dear Marine Detective, Your blog has won a Liebster Blog award from

On February 22nd, I received the following notification: “Dear Marine Detective, Your blog has won a Liebster Blog award from