Ra Ra Ratfish!

LOOK at this fish!

Those who are as in awe of the species as I am, describe it as “adorably bizarre” (Dr. Milton Love) and as “true survivors from before the dinosaurs . . . no wonder they look like they’re from another world.” (Ray Troll, source 5).

Spotted Ratfish (Hydrolagus colliei). Maximum size 1 m and 1.8 kg; females are larger than males.

©Jackie Hildering

Maybe not as flattering a description, but certainly accurate is: “They look like you put three or four things in a blender” (unnamed scientist, source 5).

Indeed, this family of fishes is aptly named the “Chimeras” for the creature from Greek mythology that is a composite of other species.

Spotted Ratfish (and a Blackeye Goby). ©Jackie Hildering.

The common name of this fish is the “Spotted Ratfish” favouring the perceived likeness to that rodent. The scientific name “Hydrolagus collieli” favours the rabbit-like resemblance with “Hydrolagus” translating into “water rabbit”.

For me, it is an exquisitely beautiful species and a source of marvel. Notice the wing-like pectoral fins; huge eyes that seem to be able to pivot back and forth in their sockets; scaleless, white-spotted skin with a silvery sheen; and the beautiful gold “stitching” that make it look all the more like it has been assembled from other parts. Oh and then there are the remarkable structures in the males! Read on for an explanation of what they’re all about.

Male Spotted Ratfish. ©2016 Jackie Hildering.

Likely Spotted Ratfish are well known to many fisher-folk in their range from the western gulf of Alaska to southern Baja California but, as a fish out of water, I think it is so difficult to see the species’ beauty. We divers are so lucky to see them below the surface and I’m hoping the photos and information below enhance an appreciation for this fish that should never, ever be referenced as “ugly”! 🙂

Source: Didier, D.A. Chimeras. http://www.fao.org/tempref/docrep/fao/009/y4160e/y4160e41.pdf

Are they sharks? The Chimeras are closely related to rays, skates and sharks. They are all cartilaginous fishes (Chondrichthyes) but sharks and rays belong to the subclass “Elasmobranchii” and the Chimaeras are in a separate subclass, the “Holocephali”. They diverged from their shark ancestors some 400 million years ago.

Senses: Like rays, skates and sharks, they have pores in their heads with which they can detect the electrical fields of their prey – even tiny heartbeats under the sand (source 5). Their huge eyes suggest that Spotted Ratfish are more active at night. Even though Spotted Ratfishes are often in the shallows, my personal observations support that their eyes are designed to function in low light. I will never forget my excitement at seeing one for the first time and, without thinking, turning my dive light on the poor guy. The result appeared to be that I temporarily blinded him. He swam forward – directly into a rock. Eek!

Close up on the head of a Spotted Ratfish. ©Jackie Hildering.

Diet: Ratfish have plate-like grinding teeth and they are reported “to have the highest jaw leverage of any cartilaginous species studied” (source 3). This makes them well-suited to be able to crush the hard bits of fish, crabs including hermit crabs, shrimp, snails, sea urchins, worms, bivalves like clams, and isopods (source 9).

Male Spotted Ratfish appearing to attack a Red Rock Crab. ©Jackie Hildering

Defences: In addition to their biting strength, Spotted Ratfish have a retractable spine with a venom gland. See it there in front of the dorsal fin? This causes some discomfort in humans but, one study revealed that it can be fatal to Pacific Harbour Seals by perforating the esophagus or stomach and migrating into vital tissues. The spines have also been found in the heads and necks of a few California and Steller Sea Lions but have not been proven to be the cause of death (source 1). In addition to seals and sea lions; Spotted Ratfishes’ predators include Sablefish; shark species like the Bluntnose Sixgill and Spiny Dogfish; birds like Buffleheads, Common Murres and Pigeon Gullemots; Humboldt Squid and, apparently, Northern Elephant Seals eat their eggs (source 9). We humans only went after Spotted Ratfish for their livers in the 1800s. We don’t like the taste of their flesh – lucky Ratfish.

Spotted Ratfish. See the spine in front of the first dorsal fin? ©2016 Jackie Hildering.

Mobility: In having such a thin, whip-like tail that can’t provide much force, propulsion in Ratfish comes from their wing-like pectoral fins. It is such a thing of beauty to see them swim, or is it fly? Like rays, skates and sharks, they have large livers that aid buoyancy whereby they can hover in the water column and then glide off.

Video: Spotted Ratfish swimming. ©Jackie Hildering.

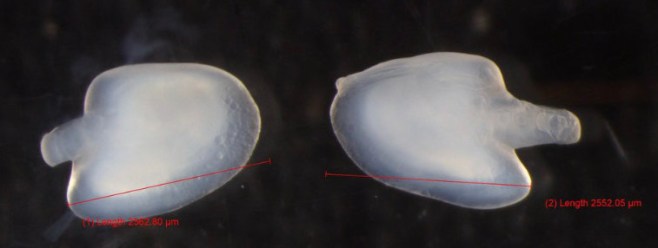

Female bits: Like many rays, sharks and skates, chimeras are “oviparous”. Fertilization is internal and then egg cases are laid. The leathery egg cases look like “little violin cases” (source 2) and each contain one egg. As seen in Wendy Carey’s remarkable photo below, they female “extrudes’ two egg cases at a time – one from each oviduct. Reportedly, they often hang from her in the water column for four to six days before falling to the ocean bottom. Then, she lays another pair (this suggests female Ratfish may be able to store sperm). The baby Ratfish develop within the egg case for 5 to 10 months and then wiggle out when they are around 14 cm. It appears to me that they spawn throughout the year but there may be a peak from May into October (source 9). Little is known about the longevity of Ratfish but preliminary research suggests that they are likely late maturing with females becoming sexually mature at age ~14 and males at age ~12 (source 7). See this link for my blog with photos of other NE Pacific Ocean fish egg cases known as “mermaid’s purses”.

Female Spotted Ratfish egg-laying. ©Wendy Carey.

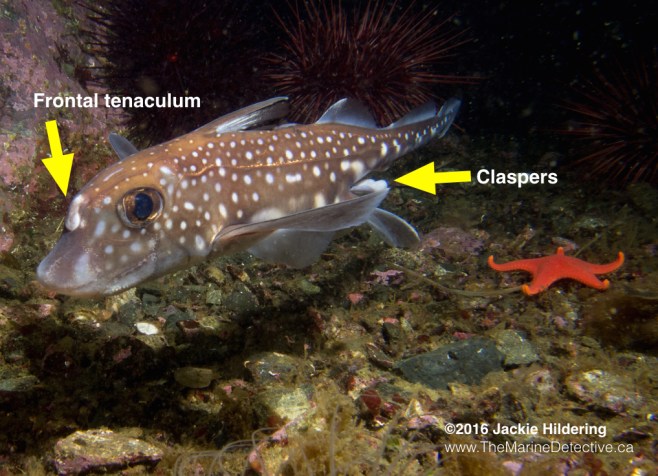

Male bits: So those “dangly bits”, what are they?

The claspers in the pelvic area you may know from shark species. They are the males’ sex organs containing sperm and they are used only one at a time to inseminate the female.

Male reproductive organs. ©2016 Jackie Hildering

Male Spotted Ratfish found dead on beach. Frontal tenaculum is being pointed out. ©Jacqui Engel.

The remarkable stalked club structure with little hooks on the male’s head is the “frontal tenaculum” and it is unique to adult males in the Chimera family. It is usually withdrawn into the groove in their foreheads but, during copulation, is used to clamp onto the female’s pectoral fin. There is also another grasping structure, the pre-pelvic tenaculum, just before the pelvic fins that also allow the male to anchor into position.

In sharks, males bite onto the female’s pelvic fin to get into position but I suggest, with Chimera’s very different teeth, this would not work well and thereby, that there was a selection pressure for such unique structures. It is noteworthy too that male Chimeras have to be much smaller than females because otherwise, with their heads attached onto the pectoral fin, they wouldn’t be able to position a clasper into the female (source 8).

Ray Troll (colourful always) describes the frontal tenaculum as a “girl grabber” but don’t let that suggest that there isn’t courtship between Ratfish. Apparently, there are colour changes and distinct swimming patterns and, once the male’s clasper is inserted in the female, they swim together like this for between 37 and 120 minutes (source 9).

I assure you, if I manage to witness Spotted Ratfish courtship or mating, there WILL be an update to this blog!

Now you know – mature male or female? ©2016 Jackie Hildering

Male Spotted Ratfish near the surface. ©Jackie Hildering.

Sources:

- Akmajian, A. M., D. M. Lambourn, M. M. Lance, S. Raverty, and J. K. Gaydos. 2012. Mortality related to Spotted Ratfish (Hydrolagus colliei) in Pacific harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) in Washington State. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 48:1057-1062. DOI: 10.7589/2011-12-348.

- Biology of Rays and Sharks; Chimaeras – The Neglected Chondrichthyans.

- Huber, D.R., Dean, M.N., Summers, A. P. 2008. . Hard prey, soft jaws and the ontogeny of feeding mechanics in the spotted ratfish Hydrolagus colliei

Journal of the Royal Society Interface 5 (25), 941-953.

- Didier, D.A. Chimeras.

- Doughton, Sandi. August 14, 2010. Rise of the Ratfish in Puget Sound. Seattle Times.

- Florida Museum of Natural History. Spotted Ratfish.

- Preliminary age, growth and maturity estimates of spotted ratfish (Hydrolagus colliei) in British Columbia. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 115: 55-63

- Klimley, Peter A. 2013. The Biology of Sharks and Rays. The University of Chicago Press.

- Love, M. 2012. Certainly More Than You Want to Know About The Fishes of The Pacific Coast—A Postmodern Experience. Copeia: …Milton S.Love Santa Barbara Really Big Press

Deep sea ROV video of what may be the species Pointy-Nose Blue Ratfish (Hydrolagus trolli) in the NE Pacific. Good general information on ratfishes in general and would mean a very significant range expansion for this species.