Rockfish vocalizations: “Knock knock, who’s there?”

I feel compelled to share this new research by Lancaster et al., 2025 with you because:

1. It is about a non-destructive / non-invasive way to study fish. Using Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM) to determine wild fish presence in the same way one would identify birds by their calls.

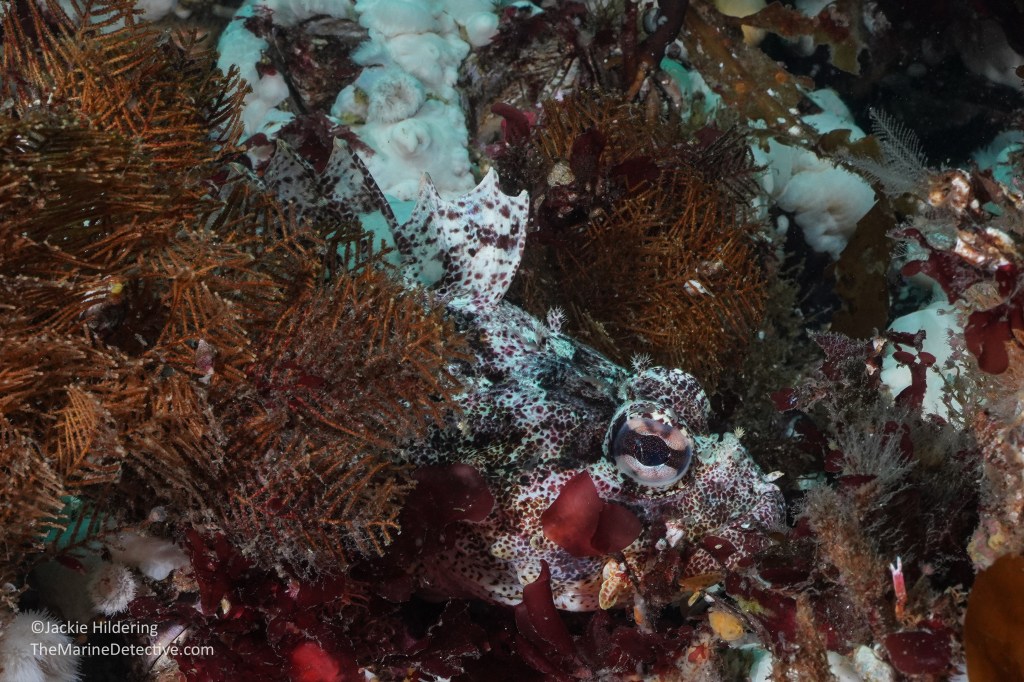

2. It is yet another example of how little we know about even common marine species. Among the eight species of fish near Vancouver Island for which vocalizations were documented by the researchers, this is the first time ever that the sounds of Canary and Vermillion Rockfish have been identified.

3. The title of the research paper is so clever: “Knock knock, who’s there? Identifying wild species-specific fish sounds with passive acoustic localization and random forest models”.

4. I know you want to see the video below and listen to the sounds!

Excerpts from the University of Victoria’s media release about the research:

“University of Victoria (UVic) biologists have discovered that even closely related fish species make unique and distinctive sounds and determined that it’s possible to differentiate between the sounds of different species. The discovery opens the door to identifying fish based on sound alone.

Using passive acoustics, the researchers identified unique sounds for eight different Vancouver Island fish species in their natural habitats. They then developed a machine learning model that can predict which sounds belonged to which species with up to 88 per cent accuracy. This could have positive implications for marine conservation efforts and allow scientists to monitor specific fish species using acoustics, says Darienne Lancaster, a PhD candidate in biology who led the project.

The research, published in the Journal of Fish Biology, is part of the larger fish sounds project run out of the Juanes Lab at UVic…

While researchers have been identifying fish sounds for years, these sounds were typically recorded in a laboratory setting, rather than in the wild and whether different species made unique sounds had never been tested.

Lancaster identified unique sounds for eight different species of fish commonly found on the coast of British Columbia: the black rockfish, quillback rockfish, copper rockfish, lingcod, canary rockfish, vermillion rockfish, kelp greenling and pile perch. This was the first time, in the lab or the wild, that sounds had been identified for the canary and vermillion rockfish.

“It has been exciting to see how many different species of fish make sounds and the behaviours that go along with these calls,” says Lancaster. “Some fish, like the quillback rockfish, make rapid grunting sounds when they’re being chased by other fish, so it’s likely a defensive mechanism. Other times, fish, like copper rockfish, will repeatedly make knocking sounds as they chase prey along the ocean floor.”

The black rockfish make a long, growling sound similar to a frog croak and the quillback rockfish make a series of short knocks and grunts…

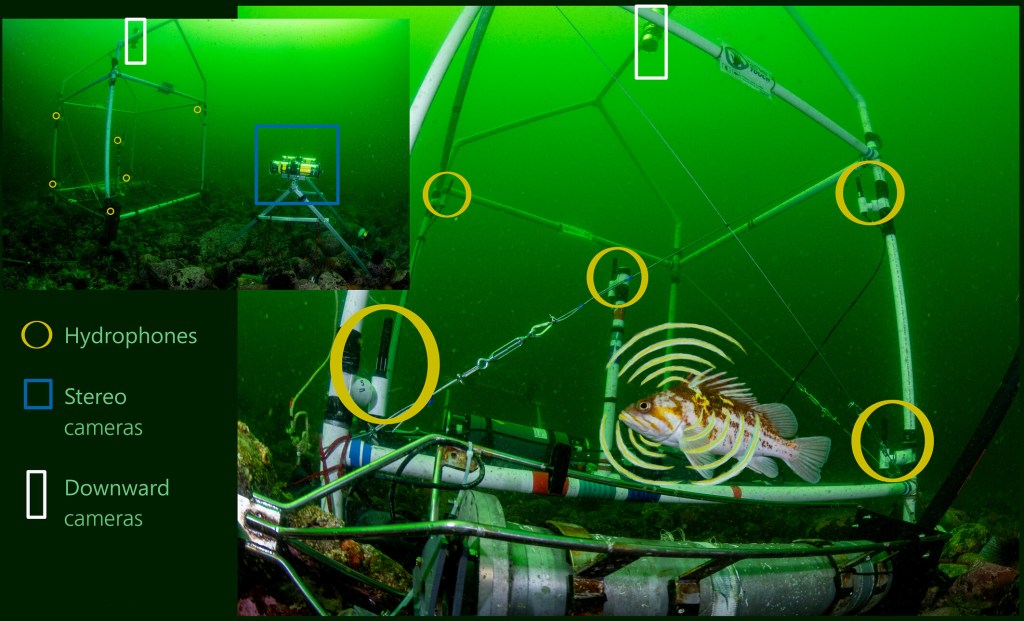

Lancaster used a technique called passive acoustic monitoring to identify the fish sounds. She collected underwater audio and video using a sound localization array designed by former UVic PhD student and project collaborator, Xavier Mouy, and then used sound characteristics to identify differences in species calls.

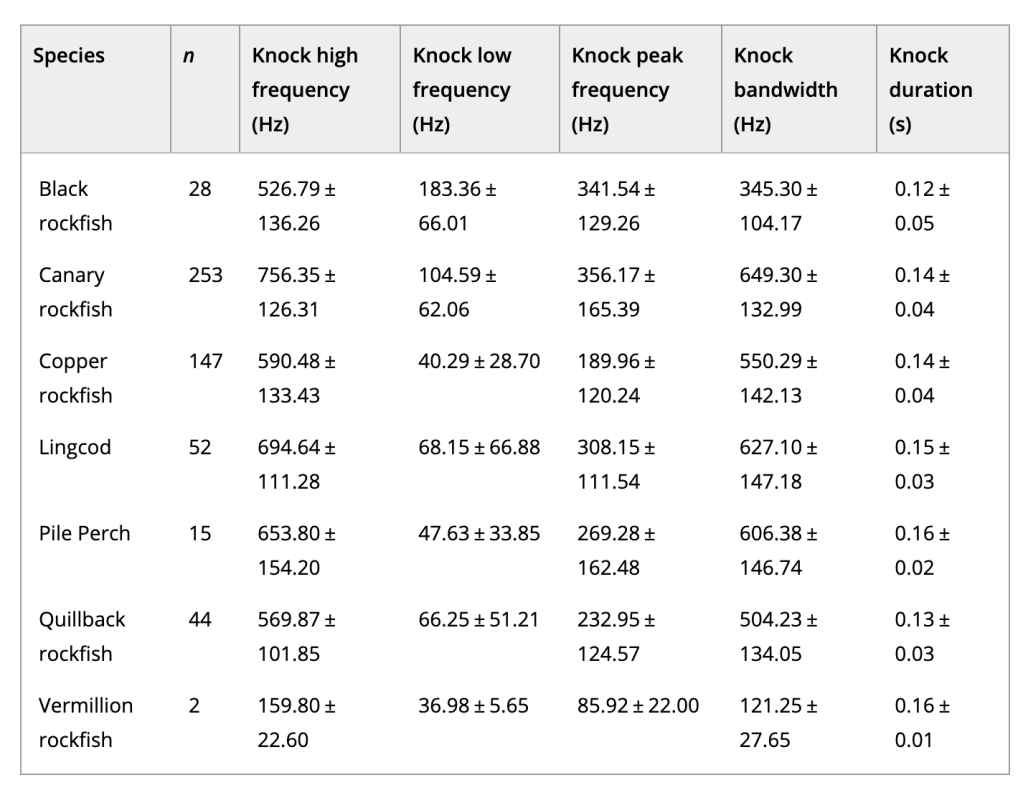

Her machine learning model used a set of 47 different sound features, such as duration and frequency, to detect small differences in each species’ sounds that can be used to tell them apart. The model used these small differences in sound features to group species calls together.

“The ability of passive acoustics to identify specific fish by sound could be an important new tool for conservationists and fisheries managers,” says Francis Juanes, UVic biology professor and principal investigator on the project. “Passive acoustics could allow us to estimate population size, monitor activity, and assess the overall health of a fish population in a way that is minimally invasive to vulnerable marine animals.”

Excerpts from the research paper’s discussion:

“We documented knocks and/or grunts for eight species of rocky reef fish. Two species—canary and vermillion rockfish—have never been documented as soniferous, and pile perch sounds have not been documented since 1966 (Meldrim & Walker, 1966). Black rockfish sounds have never been described or presented in spectrogram form (Fletcher, 1969). We provide summaries of species sound features in Tables S3–S5 and audio of species sounds are available on our data repository. We also demonstrate the importance of analysing field rather than aquarium recordings to determine if fish are soniferous and to characterize species calls. Aquarium-based studies can struggle to determine sonifery and the range of sounds in fishes’ repertoires. For example, an aquarium study by Nichols (2005) failed to elicit sounds from canary, black, and vermillion rockfish through prodding, but our study in fish habitat found that all three species are soniferous…

It was not possible to determine if kelp greenling are soniferous during this study. Kelp greenling were frequently present in videos, and we identified 25 possible kelp greenling calls with low ID confidence. Kelp greenling were typically interacting with other soniferous fish during calling activities so it was impossible to confidently determine which fish was calling. Further studies on kelp greenling calling would be useful to determine if they are soniferous.

Copper and quillback rockfish showed similar sound feature characteristics and were sometimes misclassified in the random forest knock model. This similarity is unsurprising as these two species can hybridize (Schwenke et al., 2018). However, quillback rockfish knocks and grunts had higher peak frequencies than copper rockfish sounds. We are unsure if this is a species-specific trait or an artefact of size differences across species. Higher frequency sounds often occur in smaller conspecifics (Kasumyan, 2008; Mann & Lobel, 1995; Myreberg et al., 1993; Rountree & Juanes, 2020), and larger copper rockfish are typically found at the same depth range as smaller quillback rockfish (Love et al., 2002). Future work will use our stereo-camera length information to examine size impacts on call characteristics.

This study expands the utility of PAM for assessing species richness and presence/absence, which are cornerstones of conservation and fisheries monitoring. We outline a novel method for collecting wild fish sounds and identifying species-specific sound features for use in fish sound detectors. Our study results can be used to detect the presence of specific fish species based on our documented sound parameters, which provide much greater precision than acoustic indices like ADI (Dimoff et al., 2021; Minello et al., 2021). Our work also contributes to the growing library of marine fish sounds required for PAM abundance estimation, but more localization studies are required to document the diversity of soniferous fish sounds. Future research should focus on localizing sounds for more species as well as collecting additional sound samples for underrepresented species. Further research into regional differences in species-specific calls is also recommended to determine the transferability of sound characteristics.”

You could be lucky enough to get BC researchers to provide education on fish bioacoustics: “FishSounds Educate is a free educational program that aims to use the topic of bioacoustics (biological sounds) to encourage future conservation leaders and enhance ocean literacy across Canada.” See this link.

Sources:

- Discovery of Sounds in the Sea (DOSITS) – Fish

- Fishsounds.net

- Global News, January 9, 2026, B.C. biologists identify unique sounds of 8 fish species

- Lancaster, D., Mouy, X., Haggarty, D., & Juanes, F. (2025). Knock knock, who’s there? Identifying wild species-specific fish sounds with passive acoustic localization and random forest models. Journal of Fish Biology, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.70294

- UVIC media release, December 18, 2025 “UVic researchers use AI to decipher fish sounds“

Note: I will try to get/find the sound samples of the Canary and Vermillion Rockfish. They have not yet been uploaded to Fishsounds.net. From that resource I did find the samples of the vocals of these species referenced in the research:

- Copper Rockfish – listen via this link.

- Lingcod –listen via this link.

- Pile Perch – listen via this link.

And for more vocals from fish (and other species) go to the “Discovery of Sounds in the Sea (DOSITS)” website. You do NOT want to miss the sounds of the Plainfin Midshipman, another common species off our coast. Then also go to this Nature of Things clip featuring this species with expert input from Sarika Cullis-Suzuki who did her PhD research on Plainfin Midshipman.