Wasted. What is happening to the sea stars of the northeast Pacific Ocean?

I published this blog near the beginning of the onset of Sea Star Wasting Disease (SSWD) in 2013. It has been updated since 2013 with research developments. See the original blog at the end, which includes photos of the progression of SSWD.

Last update: February 9, 2026

Good summative news story on the history of the research into Sea Star Wasting – National Post, February 9, 2026 “Sea star murder mystery: What’s killing a key ocean species?”

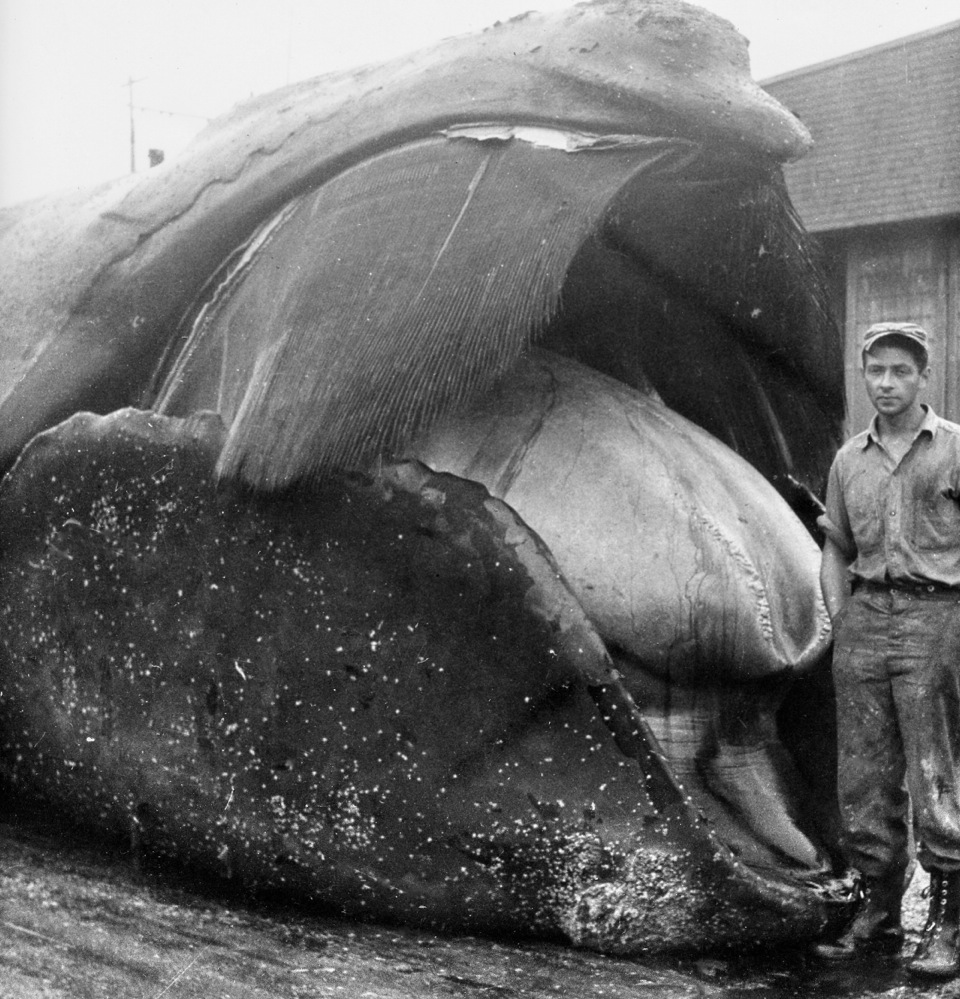

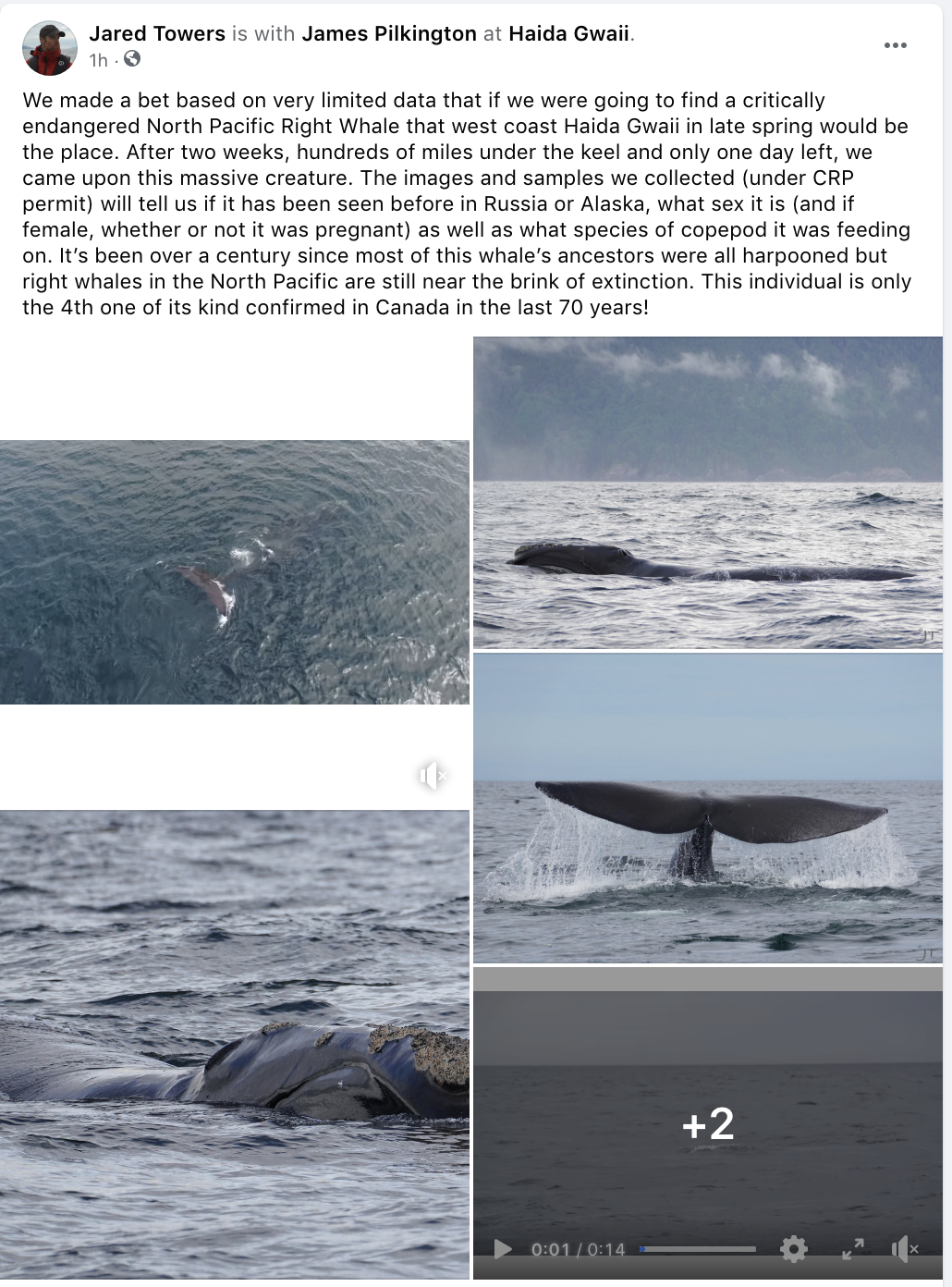

Background: Since 2013, more than twenty species of sea star have been impacted by Sea Star Wasting Disease from Mexico to Alaska. There is local variation in the intensity of the disease and which species are impacted. It is one of the largest wildlife die-off events in recorded history. Sea stars contort, have lesions, shed arms and become piles of decay. Sunflower Stars (the world’s biggest sea star species) remain devastated with far-reaching impacts on kelp forests and the marine ecosystem.

Where to relay sea star data (of great value in understanding the survival, species impacted, range, and potentially, contributing factors of Sea Star Wasting Disease (SSWD):

- University of California Santa Cruz via this link or email seastarwasting@googlegroups.com with species, depth, time, location, photo, and ideally GPS coordinates).

- Or, if you already contribute to iNaturalist, provide your sightings there https://inaturalist.ca.

February 9, 2026 – Good summative news story on the history of the research into Sea Star Wasting – National Post, “Sea star murder mystery: What’s killing a key ocean species?”

August 4, 2025 – Very big breakthrough:

After more than 10 years, the causative agent for Sea Star Wasting Disease (SSWD) has been found. Bacteria – Vibrio pectenicida (in the same family as bacteria that causes Cholera in humans).

Media release includes: “Now that scientists have identified the pathogen that causes SSWD, they can look into the drivers of disease and resilience. One avenue in particular is the link between SSWD and rising ocean temperatures, since the disease and other species of Vibrio are known to proliferate in warm water . . .”

Research paper includes: “Vibrio spp. have been coined ‘the microbial barometer of climate change’, because of the increasing prevalence of pathogenic species associated with warming water temperatures. Given that existing evidence indicates a relationship between increasing seawater temperature and SSWD incidence, an important next phase of research will be to empirically define this relationship, a goal now possible as a result of the identification of a causative agent.”

Prentice, M. B., Crandall, G. A., Chan, A. M., Davis, K. M., Hershberger, P. K., Finke, J. F., Hodin, J., McCracken, A., Kellogg, C. T. E., Clemente-Carvalho, R. B. G., Prentice, C., Zhong, K. X., Harvell, C. D., Suttle, C. A., & Gehman, A. M. (n.d.). Vibrio pectenicida strain FHCF-3 is a causative agent of sea star wasting disease. Nature Ecology & Evolution.

____________________________

May 15, 2025 – Very important development:

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) is recommending to the Government of Canada that Sunflower Stars be protected as an endangered species under Canada’s Species at Risk Act. This was decided at their May 8, 2025 meeting.

Why share the information about Sea Star Wasting Disease and put the effort into tracking and educating about the research?

It is often marine species that testify to environmental problems first, serving as indicators for the resources upon which we too depend. The hypothesis remains that the sea stars have succumbed in an unprecedented way because of changed ocean conditions (stressors). Too few of us realize the importance of sea stars in the ocean food web (see video below) let alone the importance of what they might be indicated about environmental health.

Quote from Drew Harvell, Cornell University professor of ecology and evolutionary biology who studies marine diseases: “these kinds of events are sentinels of change. When you get an event like this, I think everybody will say it’s an extreme event and it’s pretty important to figure out what’s going on . . . Not knowing is scary . . . If a similar thing were happening to humans, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would commit an army of doctors and scientists to unraveling the mystery.“

Below, January 30, 2019 video by the Hakai Institute re. Sunflower Stars and Sea Star Wasting Disease.

Research on Sea Star Wasting Syndrome in reverse chronological order:

June 6, 2025

Mancuso RT, Gravem SA,Campbell RS, Hunter N, Raimondi P, Galloway AWE, Kroeker KJ. 2025 Sunflower sea star chemical cues locally reduce kelp consumption by eliciting a flee response in red sea urchins. Proc. R.Soc. B 292: 20250949.

Research suggests that Sunflower Stars can be 15 metres away and still help with deterring urchins, specifically red urchins.

April 2, 2025

Gehman AM, Pontier O, Froese T, VanMaanen D, Blaine T, Sadlier-Brown G, Olson AM, Monteith ZL, Bachen K, Prentice C, Hessing-Lewis M, Jackson JM. Fjord oceanographic dynamics provide refuge for critically endangered Pycnopodia helianthoides. Proc Biol Sci. 2025

June 2024

An analysis of how there was initially an incorrect pathogen identified for SSWD (a densovirus).

Hewson, I., Johnson, M. R., & Reyes-Chavez, B. (2024). Lessons Learned from the Sea Star Wasting Disease Investigation. Annual Review of Marine Science. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-040623-082617

July 19, 2023

Andrew R. McCracken et al, Microbial dysbiosis precedes signs of sea star wasting disease in wild populations of Pycnopodia helianthoides, Frontiers in Marine Science (2023).

March 15, 2023 Announcement by NOAA: Recommendation by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association that Sunflower Stars receive protection as a Threatened species under the American Endangered Species Act.

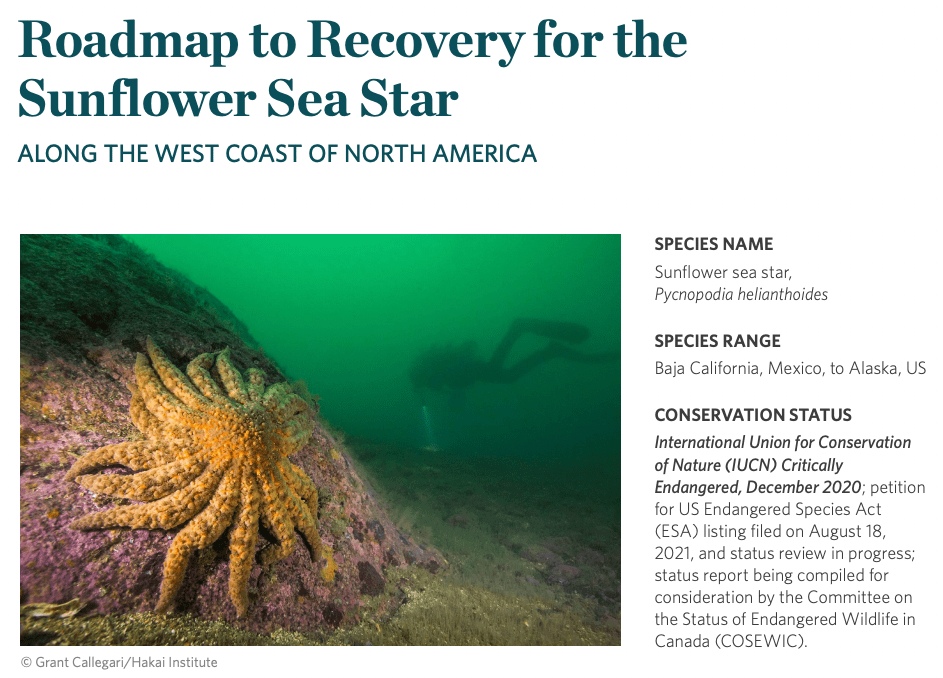

Sunflower Stars are already recognized as Critically Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature but this does not offer them protection in Canada or the US. In Canada, an “unsolicited assessment” has been provided to the Committee on the Status on Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) in hopes of expediting the protection of Sunflower Stars under Canada’s Species at Risk Act.

The March 15 announcement by NOAA includes: “While Sea Star Wasting Syndrome is not well understood, it appears to be exacerbated by rapid changes in water temperature, warmer ocean temperatures, and other physical stressors. Outbreaks are likely to recur as the climate continues to warm. Outbreaks may also be more frequent or spread more quickly . . . Populations of the species appear relatively more viable are in cooler, and possibly deeper, waters to the north, including Alaska, British Columbia, and the Salish Sea in the Pacific Northwest. Losses due to the syndrome in these waters were not as high as in more southerly waters.”

February 22, 2023

Galloway A. W. E., Gravem S. A., Kobelt J. N., Heady W. N., Okamoto D. K., Sivitilli D. M., Saccomanno V. R., Hodin J. and Whippo R. 2023. Sunflower sea star predation on urchins can facilitate kelp forest recovery Proc. R. Soc. B. 29020221897.20221897

December 2022: Roadmap to recovery for the sunflower sea star (Pycnopodia helianthoides) along the west coast of North America. The Nature Conservancy (Heady et al).

From the Executive Summary:

“A sea star wasting disease (SSWD) event beginning in 2013 reduced the global population of sunflower sea stars by an estimated ninety-four percent, triggering the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to classify the species as Critically Endangered. Declines of ninety-nine to one hundred percent were estimated in the outer coast waters of Baja California, California, Oregon, and Washington. From the Salish Sea to the Gulf of Alaska, declines were greater than eighty-seven percent; however, there is uncertainty in estimates from Alaska due to limited sampling. A range-wide species distribution analysis showed that the importance of temperature in predicting sunflower sea star distribution rose over fourfold following the SSWD outbreak, suggesting latitudinal variation in outbreak severity may stem from an interaction between disease severity and warm waters. Given the widespread, rapid, and severe declines of sunflower sea stars, the continued mortality from persistent SSWD, and the potential for the disease to intensify in a warming future ocean, there is a need for a Roadmap to Recovery to guide scientists and conservationists as they aid the recovery of this Critically Endangered species . . . The area of greatest concern and need for immediate action common to all geographic regions is understanding disease prevalence and disease risk. Here we use the term “disease” to describe SSWD, also known as Sea Star Wasting Syndrome or Asteroid Idiopathic Wasting Syndrome, which affects some twenty species of sea stars and the cause(s) of which remain unknown and under debate in the literature. Much work is needed to improve our understanding of SSWD, the cause(s) of SSWD, how SSWD impacts wild sunflower sea stars, SSWD dynamics in a multi-host system, and to discover and develop measures to mitigate SSWD impacts and risks associated with conservation actions.”

December 29, 2021 – assessment report for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature = Gravem, S.A., W.N. Heady, V.R. Saccomanno, K.F. Alvstad, A.L.M. Gehman, T.N. Frierson and S.L. Hamilton. 2021. Pycnopodia helianthoides. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021.

January 1, 2022 (first published in October 8, 2021) Burton, A. R., Gravem, S. A., & Barreto, F. S. (January 01, 2022). Little evidence for genetic variation associated with susceptibility to sea star wasting syndrome in the keystone species Pisaster ochraceus. Molecular Ecology, 31, 1, 197-205.

August 2021: Hamilton S. L., Saccomanno V. R., Heady W. N., Gehman A. L., Lonhart S. I., Beas-Luna R., Francis F. T., Lee L., Rogers-Bennett L., Salomon A. K. and Gravem S. A. (2021) Disease-driven mass mortality event leads to widespread extirpation and variable recovery potential of a marine predator across the eastern Pacific. Proc. R. Soc. B.288

June 2021: Jackson, E.W., Wilhelm, R.C., Johnson, M.R., Lutz, H., Danforth, I., Gaydos, J., Hart, M., & Hewson, I. (2020). Diversity of Sea Star-Associated Densoviruses and Transcribed Endogenous Viral Elements of Densovirus Origin. Journal of Virology, 95.

January 2021: Aquino CA, Besemer RM, DeRito CM, Kocian J, Porter IR, Raimondi PT, Rede JE, Schiebelhut LM, Sparks JP, Wares JP and Hewson I (2021) Evidence That Microorganisms at the Animal-Water Interface Drive Sea Star Wasting Disease. Front. Microbiol. 11:610009. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.610009. See Cornell University coverage of this research “Organic matter, bacteria doom sea stars to oxygen depletion”. Also, see further communication from one of the lead researchers, Dr. Ian Hewson, at this link.

This research suggests that the pathogen is not a virus but a bacteria. The research puts forward that warmer oceans and increased organic matter appear to lead to increases in specific bacteria (copiotrophs) that then use up the oxygen at the interface of the sea star and the bacteria, and the sea stars can’t breathe. The hypothesis includes that “more heavily affected species were rougher and therefore had a much larger boundary layer (the layer at the animal-water interface) than those species which were less affected.”

November 2020: Hewson, I.; Aquino, C.A.; DeRito, C.M. Virome Variation during Sea Star Wasting Disease Progression in Pisaster ochraceus (Asteroidea, Echinodermata). Viruses 2020, 12, 1332.

Rogers-Bennett, L., & Catton, C. A. (2019). Marine heat wave and multiple stressors tip bull kelp forest to sea urchin barrens. Scientific Reports, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51114-y

Harvell, C. D., Montecino-Latorre, D., Caldwell, J. M., Burt, J. M., Bosley, K., Keller, A., Heron, S. F., … Gaydos, J. K. (January 01, 2019). Disease epidemic and a marine heat wave are associated with the continental-scale collapse of a pivotal predator (Pycnopodia helianthoides). Science Advances, 5, 1.)

Quote from lead author: “The main takeaway is the speed with which a multi-host infectious disease can cause decline in the most susceptible host [Sunflower Stars] and that warming temperatures can field bigger impacts of disease outbreaks.” Abstract includes: “Since 2013, a sea star wasting disease has affected >20 sea star species from Mexico to Alaska. The common, predatory sunflower star (Pycnopodia helianthoides), shown to be highly susceptible to sea star wasting disease, has been extirpated across most of its range. Diver surveys conducted in shallow nearshore waters (n = 10,956; 2006–2017) from California to Alaska and deep offshore (55 to 1280 m) trawl surveys from California to Washington (n = 8968; 2004–2016) reveal 80 to 100% declines across a ~3000-km range. Furthermore, timing of peak declines in nearshore waters coincided with anomalously warm sea surface temperatures. The rapid, widespread decline of this pivotal subtidal predator threatens its persistence and may have large ecosystem-level consequences.”

The paper’s discussion includes: “Cascading effects of the P. helianthoides loss are expected across its range and will likely change the shallow water seascape in some locations and threaten biodiversity through the indirect loss of kelp. P. helianthoides was the highest biomass subtidal asteroid across most of its range before the Northeast Pacific SSWD event. Loss or absence of this major predator has already been associated with elevated densities of green (Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis), red (Mesocentrotus franciscanus), and purple urchins (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) across their range, even in regions with multiple urchin predators. Associated kelp reductions have been reported following the outbreak . . . SSWD, the anomalously warm water, P. helianthoides declines, and subsequent urchin explosions . . . have been described as the “perfect storm.” This “storm” could result not only in trophic cascades and reduced kelp beds but also in abalone and urchin starvation.”

Burt JM, Tinker MT, Okamoto DK, Demes KW, Holmes K, Salomon AK (2018) Sudden collapse of a mesopredator reveals its complementary role in mediating rocky reef regime shifts. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 285(1883): 20180553.

Sunflower Stars are of great ecological importance in maintaining kelp forests. Burt et al in 2018 quantifies the importance of Sunflower Stars in maintaining kelp forests. Sunflower Stars feed on Green Urchins which graze on kelp. Findings included that the decline of Sunflower Stars “corresponded to a 311% increase in medium urchins and a 30% decline in kelp densities”. The loss of kelp forests can impact many other ecologically and commercially important species that relay upon them as habitat and food. Note too that our reliance on kelp forests includes oxygen production and carbon dioxide buffering.

Hewson I, Bistolas KSI, Quijano Cardé EM, Button JB, Foster PJ, Flanzenbaum JM, Kocian J and Lewis CK (2018) Investigating the Complex Association Between Viral Ecology, Environment, and Northeast Pacific Sea Star Wasting. Front. Mar. Sci. 5:77. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00077

Schiebelhut, Lauren (2018), Supporting Files for Schiebelhut LM, Puritz JB & Dawson MN (2018) Decimation by sea star wasting disease and rapid genetic change in a keystone species, Pisaster ochraceus PNAS, UC Merced Dash, Dataset.

This research, specifically on Ochre Stars, found that the genetic makeup of the species has changed since the outbreak. Young Ochre Sea Stars are more similar genetically to adults who survived than to those who succumbed. This “may influence the resilience of this keystone species to future outbreaks”. The findings of an additional March 2018 paper (Miner et al) include ” . . . we documented higher recruitment of P. ochraceus [Ochre Stars] in the north than in the south, and while some juveniles are surviving (as evidenced by transition of recruitment pulses to larger size classes), post-SSWD survivorship is lower than during pre-SSWD periods.

Miner CM, Burnaford JL, Ambrose RF, Antrim L, Bohlmann H, Blanchette CA, et al. (2018) Large-scale impacts of sea star wasting disease (SSWD) on intertidal sea stars and implications for recovery. PLoS ONE 13(3): e0192870. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192870

___________________________________________

The content below is from my original blog November 10, 2013:

There has already been much reporting on the gruesome epidemic spreading like wildfire through several species of sea star in the NE Pacific Ocean.

“Sea Star Wasting Syndrome” is incredibly virulent and is causing the mass mortality of some sea star species in British Columbia and beyond. “Sea stars go from “appearing normal” to becoming a pile of white bacteria and scattered skeletal bits is only a matter of a couple of weeks, possibly less than that” (Source #1).

What I have strived to do is bundle the state of knowledge, relying heavily on the expertise of two extraordinary divers and marine naturalists: (1) Neil McDaniel, marine zoologist and underwater photographer / videographer who maintains a website on local sea stars and has put together A Field Guide to Sea Stars of the Pacific Northwest, and (2) Andy Lamb, whose books include Marine Life of the Pacific Northwest.

I am hoping that kayakers, beach-walkers and fellow divers will help monitor and report on the spread of the disease but I am also hoping that all of us may learn from this tragedy that has impacted “one of the most iconic animals on the coast of British Columbia . . . more abundant and diverse in our waters than anywhere else in the world” (Source #3).

Sea Star Wasting Syndrome reminds us of the fragility of ocean ecosystems; how very quickly disease could spread in the ocean; and how we are all empowered to reduce stressors that increase the likelihood of pathogens manifesting as disease (e.g. climate change) or even that pathogens enter the environment (e.g. sewage).

Species impacted?

High mortalities (note that the first 4 are members of the same family – the Asteriidae):

- Sunflower star (Pycnopodia helianthoides) hardest hit in southern British Columbia. From communication with Neil McDaniel ” . . .so far I estimate it has killed tens, possibly hundreds of thousands of Pycnopodia in British Columbia waters.”

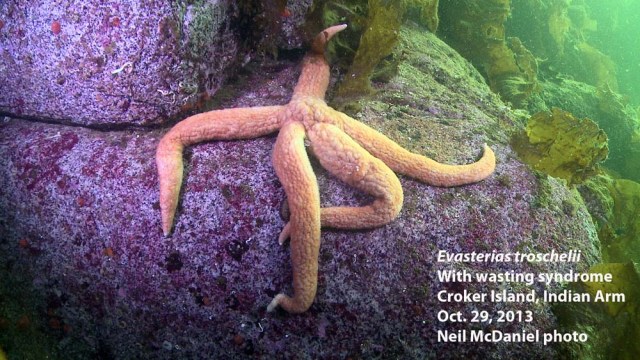

- Mottled star (Evasterias troschelii)

- Giant pink star (Pisaster brevispinus)

- Ochre star aka purple star (Pisaster ochraceus)

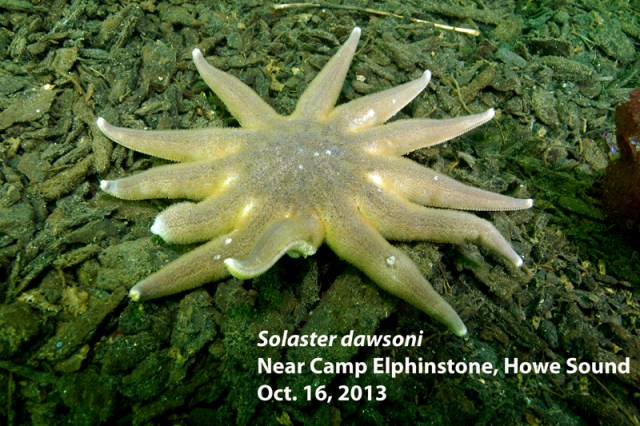

- Morning sun star (Solaster dawsoni)

More limited mortalities:

- Vermillion star (Mediaster aequalis); video of an afflicted star here.

- Rainbow star (Orthasterias koehleri)

- Leather star (Dermasterias imbricata)

- Striped sun star (Solaster stimpsoni)

- Six-rayed stars (Leptasterias sp.)

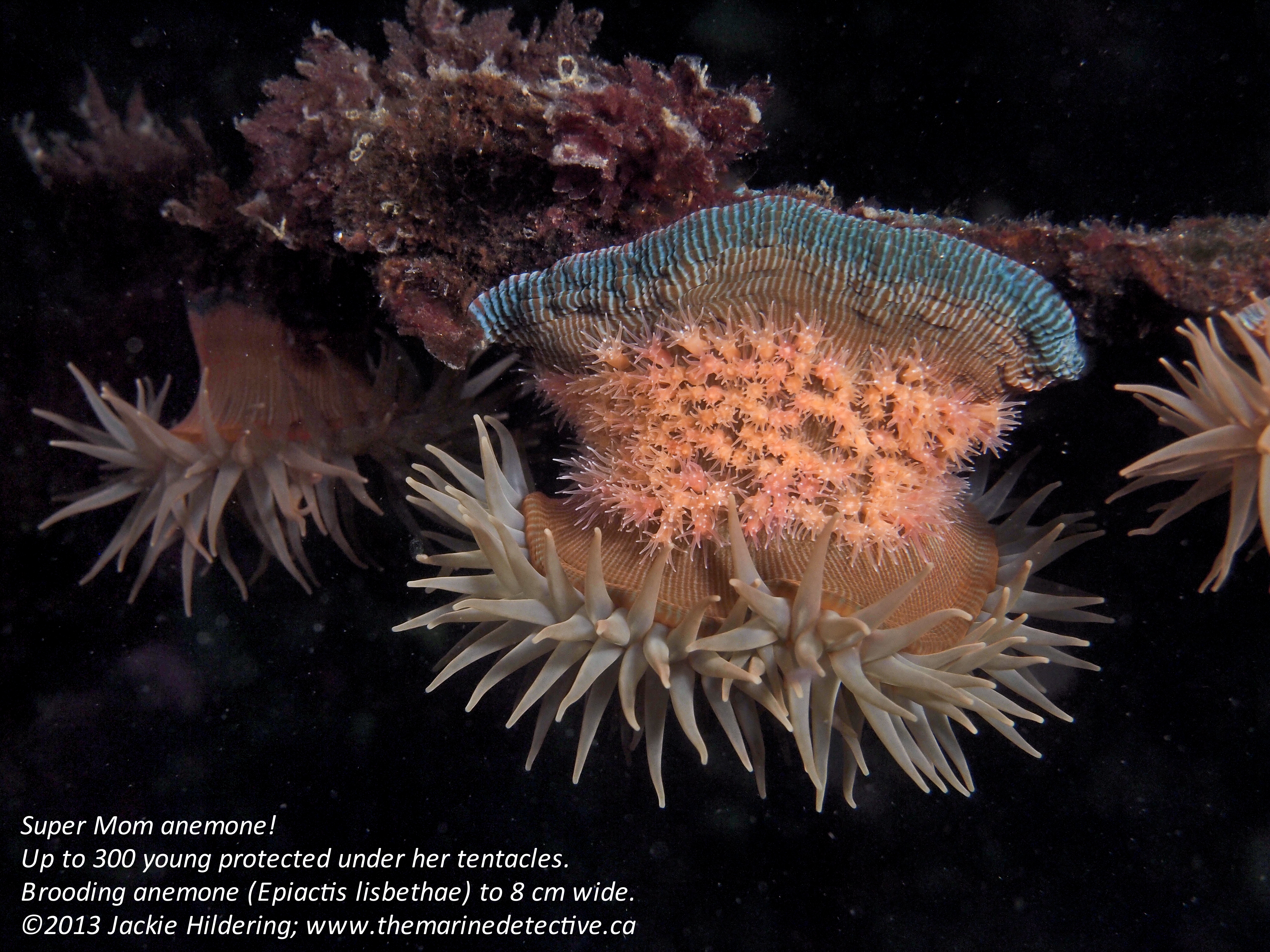

Update January 21st, 2014: Possibly: Rose star (Crossaster papposus) – I have noted symptoms in this species on NE Vancouver Island as has Neil McDaniel in S. British Columbia).

Symptoms and progression of SSWD:

Neil McDaniel shared the following 7 images for the progression of the disease in Sunflower Stars [Source #2 and #14]. See the end of this blog item for images showing symptoms in other sea star species as well as a 1 minute time-lapse clip showing the progression of the syndrome in a Sunflower Star over 7 hours. [Note that the progression of the Syndrome on NE Vancouver Island appears that it may be different from what has been observed further to the south.]

1. In this image most of the Sunflower Stars appear healthy “other than one just right of center frame is exhibiting the syndrome, looking “thinned-out” and emaciated.”

2. This images “shows this thinning in close-up. Note how distinct the edges of the rays look and how flat the star is.”

3. This image “shows how the body wall begins to rupture, allowing the gonads and pyloric caeca to spill out.”

4. This image “shows the gonads breaking through holes in the body wall. At this point rays often break off and crawl away briefly.”

5. As things progress, the animals lose the ability to crawl [and hold grip surfaces] and may even tumble down steep slopes and end up in pile at the bottom. Soon after they die and begin to rot.

6. The bacteria Beggiatoa then takes over and consumes all of the organic matter, leaving a scattering of skeletal plates on the bottom. The syndrome develops quickly and in only one to two weeks animals can go from appearing healthy to a white mat of bacteria and skeletal plates

7. This image “shows an individual star that is being consumed by mat bacteria.”

The 1-minute time-lapse video below shows the progression of the Syndrome in a sunflower star over 7 hours.

Cause(s)?

To date, the cause(s) have not yet been identified. Scientific opinion appears to be that most likely the cause is one or more viruses or bacteria. As with any pathogen (like the flu virus), the expression of a pathogen as disease is influenced by the number and proximity of individuals and could be exacerbated by environmental stressors.

Has this happened before?

Never to this large a scale. “Although similar sea star wasting events have occurred previously, a mortality event of this magnitude, with such broad geographic reach has never before been documented.” (Source #17).

- “Southern California in 1983-1984 and again (on a lesser scale) in 1997-98” (Source #4 and #13)

- Florida (Source #5).

- Update November 30: Sunflower die offs [on much smaller scale] have been noted in the past in Barkley Sound. In 2008 ochre star die offs were documented in Barkley Sound. In 2009 Bates et. al. reported on this and observed that the prevalence of disease “was highly temperature sensitive and that populations in sheltered bays appeared to sustain chronic, low levels of infection.” (Source #14 and #15).

- “Similar events have occurred elsewhere over the last 30 years. Sea stars have perished in alarming numbers in Mexico, California and other localities” (Source #2).

- “In July, researchers at the University of Rhode Island reported that sea stars were dying in a similar way from New Jersey to Maine . . a graduate student collected starfish for a research project and then watched as they “appeared to melt” in her tank” (Source #5).

Sources:

- Email communication with Neil McDaniel.

- Email communication with Andy Lamb.

- http://www.vanaqua.org/act/research/sea-stars

- http://www.eeb.ucsc.edu/pacificrockyintertidal/data-products/sea-star-wasting/

- http://commonsensecanadian.ca/alarming-sea-star-die-off-west-coast/

- http://www.businessinsider.com/disease-ravaging-west-coast-starfish-2013-11

- Shellfish Health Report from the Pacific Biological Station (DFO) conducted on 1 morning sun star and 7 sunflower stars collected on October 9, 2013 at Croker Island, Indian Arm; case number 8361.

- Email communication with Jeff Marliave.

- http://www.reef2rainforest.com/2013/11/09/disaster-deja-vu-all-over-again/

- http://www.aquablog.ca/2013/11/family-relations-in-starfish-wasting-syndrome/

- http://www.komonews.com/news/eco/Whats-causing-our-sea-stars-to-waste-away–231982671.html

- http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/sea-stars-are-wasting-away-in-larger-numbers-on-a-wider-scale-in-two-oceans/2013/11/22/05652194-4be1-11e3-be6b-d3d28122e6d4_story.html

- https://science.nature.nps.gov/im/units/medn/symposia/5th%20California%20Islands%20Symposium%20(1999)/Marine%20Ecology/Eckert_Sea_Star_Disease_Population_Decline.pdf

- Sea star wasting syndrome, Nov 30-13; https://themarinedetective.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/sea-star-wasting-syndrome-nov-30-13.pdf

- Bates AE, Hilton BJ, Harley, CDG 2009. Effects of temperature, season and locality on wasting disease in the keystone predatory sea star Pisaster ochraceus. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms Vol. 86:245-251 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20066959

- Video showing impacts in Elliott Bay, Seattle http://earthfix.info/flora-and-fauna/article/sea-stars-dying-off-west-seattle/

- University of California, Santa Cruz Press Release; December 22, 2013; Unprecedented Sea Star Mass Mortality Along the West Coast of North America due to Wasting Syndrome

- Vancouver Aquarium; January 21, 2014; Presentation – Mass Dying of Seastars in Howe Sound and Vancouver Harbour (Dr. Jeff Marliave and Dr. Marty Haulena).

- Earth Fix; January 30, 2014; Northwests starfish experiment gives scientists clues to mysterious mass die-offs

Images showing symptoms in other sea star species:

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Click to enlarge.

Sources:

Sources: