Grunt Sculpin – Little Fish, BIG Attitude!

Last updated: March 4, 2024

Meet the fish that so often has people exclaiming “It lives HERE?!”

Yep, the tiny Grunt Sculpin is a powerful ambassador for raising awareness about the depth of biodiversity hidden in the cold, dark, rich waters of the north east Pacific.

We are programmed to associate warm waters with exotic-looking fish species but read below for the Grunt Sculpin’s astounding adaptations and masterful mimicry.

The species reaches only a maximum of ~9 cm.

It is adapted to look like a Giant Acorn Barnacle (Balanus nubilis)! When facing outward, its pointy nose looks like a closed Giant Acorn Barnacle and when the fish turns around, its tail looks like the foot of the barnacle that rakes in plankton.

This little fish has giant attitude. It can be highly territorial, hopping around on its pectoral fins in a strutting, jerky fashion.

You may think the males are the master strutters? Ha! The female is as fierce as can be. Reportedly, she will chase a male into a crack, an empty barnacle shell, or another place of no escape and guard him there until she is ready to lay her eggs. When she has laid them, the male is released to do his duty.

She watches him to ensure he fertilizes the eggs (up to 150 at a time) and then, according to some sources – she saunters off leaving the male to care for the eggs but may return once in a while to take on a shift

From Casey Cook, aquarist with the Aquarium of the Pacific (pers com 2022-12-19): “The female often pushes the male into guarding so she can roam. She will get very vocal, and demanding – making sure he does the job!”

From Fishes of the Salish Sea – Volume Three: After the eggs are fertilized ” . . . she then moves off leaving the male behind to guard the nest, although she may return occasionally to help with parental duties. When the time for hatching approaches, the guarding fish takes the eggs inside its mouth, swims out of the nest, and spits out the eggs into the water column. This breaks the egg shells and frees the larvae that then swim off as zooplankton.”

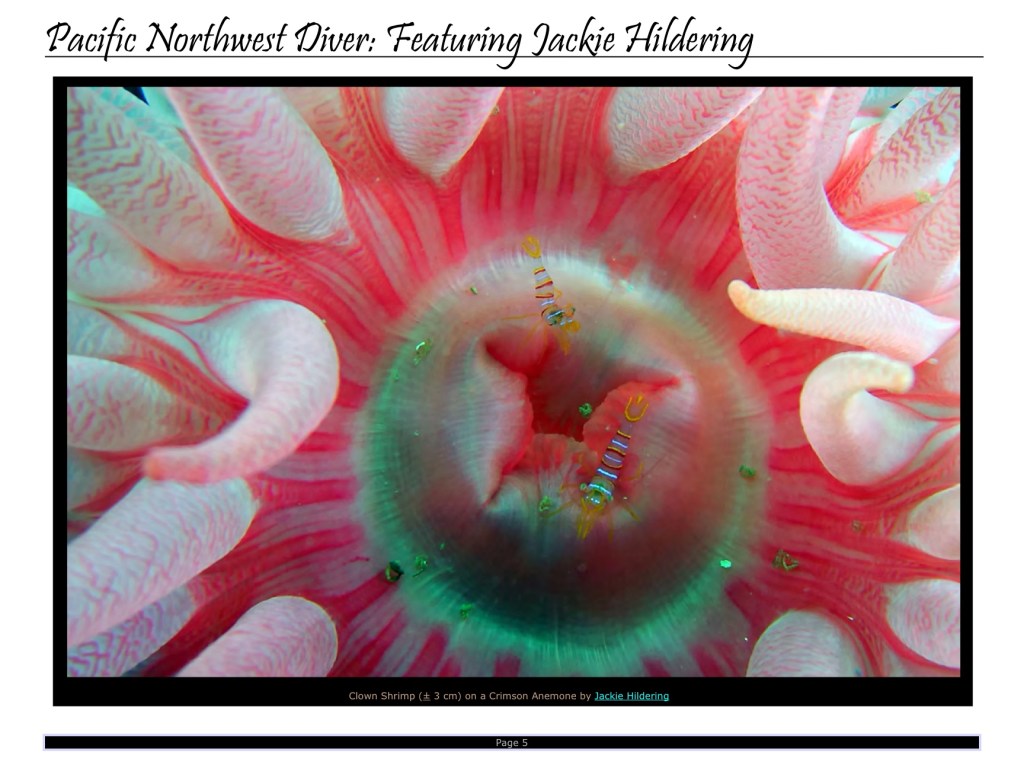

About Grunt Sculpins’ diet also from Fishes of the Salish Sea: “With its small, pointed mouth, it is adept at removing a wide variety of small invertebrates from the water column, especially copepods, amphipods, isopods and shrimps., but it also consumes significant numbers of fish eggs and larvae.”

With regards to classification, the scientific name Rhamphocottus richardsonii reflects the Greek word for beak “rhamphos” which is appropriate for the Grunt Sculpin’s bill-like snout. This makes some people think that the species looks like a seahorse but note that they are not closely related at all. The Grunt Sculpin is the only member of its genus. It is truly one of a kind.

Oh, and are you wondering about the name “Grunt” Sculpin? Apparently the species grunts when it is taken out of the ocean. You would too! Likely it also grunts when being defensive underwater. It is also the sound I make in my delight when I find one. It will be a very loud grunt indeed if I ever find one guarding eggs or with its tail-end extended out of a barnacle.

Below, more of my photos of Grunt Sculpins. 🙂

And some more photos of individuals to show how similar their markings are.

Sources:

– Aquarium of the Pacific – Grunt Sculpin

– Fishbase – Grunt Sculpin

– Love, M. S. (2011). Certainly more than you want to know about the fishes of the Pacific Coast: A postmodern experience. Santa Barbara, Calif: Really Big Press.